This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

October 2024 - The White Cottage, Surrey

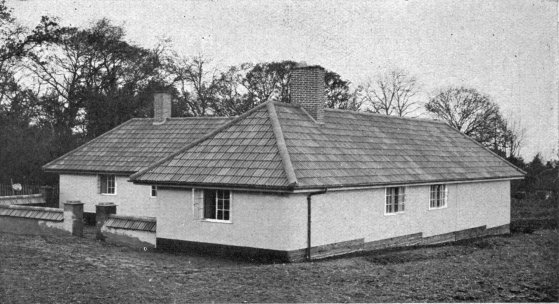

The White Cottage, Surrey

Clough Williams-Ellis, 1919

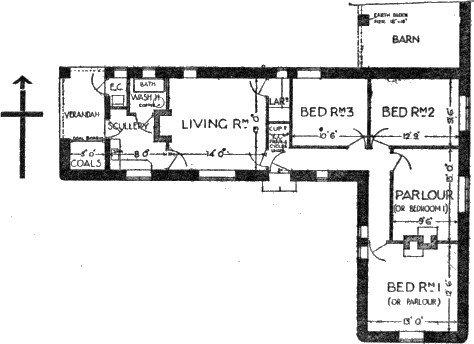

The White Cottage is located at Newlands Corner, on top of the North Downs and close to the ancient Pilgrims Way. It is a spot the illustrator Eric Parker once said had ‘the loveliest views in Surrey’. It is, in many ways, quintessential rural England. The cottage itself is buried behind hedgerows and is scarcely visible from the road. Glimpses of it reveal a rather ordinary, L-shaped bungalow. However, the cottage, despite its unassuming appearance, has an unusual place in the history of construction and energy efficiency. The original White Cottage was built in 1919 and designed by Clough Williams-Ellis as a demonstration building for rammed earth construction, also known as pisé.

Williams-Ellis is known to many as the architect of Portmeirion in North Wales, a splendid Italianate folly and his life’s work. He was also a prolific writer and advocate of many causes. He is known for his campaigning against the insensitive development of the countryside, writing England and the Octopus in 1928, helping to found the Campaigns to Protect Rural England and Wales, and influencing Ferguson’s Gang – a group of mostly women who acted as guerilla activists and fundraisers for the National Trust in the 1930s and 1940s. He was interested in history and tradition, drawing on vernacular forms of construction and applying them to his own contemporary context.

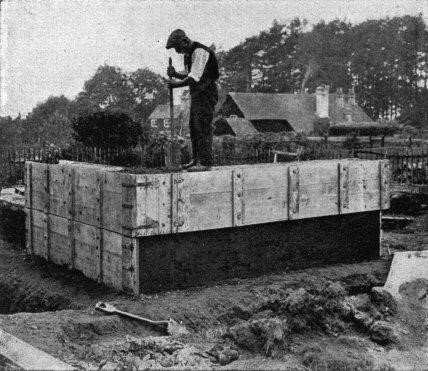

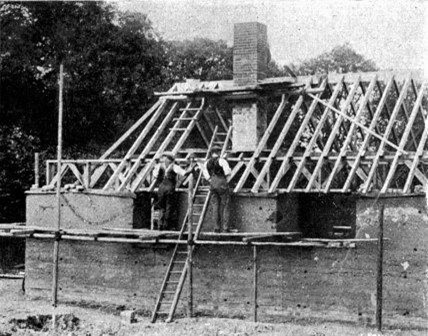

During the First World War, while serving in the army, Williams-Ellis began experimenting with pisé construction, building an apple store and a dining room for convalescent soldiers at Newlands Corner. The land was owned by John St Loe Strachey, editor of The Spectator. Williams-Ellis would go on to marry Strachey’s daughter, Amabel, in 1920 – which probably explains Strachey’s indulgence of financing experimental architecture by an inexperienced architect. Through these experiments Williams-Ellis taught himself about building with rammed earth. In 1919, immediately after leaving the army, he built the White Cottage, also at Newlands Corner, and documented it in the book Cottage Building in Cob, Pisé, Chalk & Clay: A Renaissance.

The cottage and the book was Williams-Ellis’ response to the crisis of the moment: ‘Briefly the problem is this: To provide a maximum of new housing with a minimum expenditure of labour, money, transport, and manufactured materials.’ There was a particular shortage of houses, as well as the materials and labour to build them, after the First World War. In the book, he advocated for building with earth as a solution to the housing crisis, or, at least, as a way to build rural homes. Williams-Ellis touted that earth was cheap and readily available. At Newlands Corner, he estimates that the walls of the White Cottage cost £20 to build compared to £200 that might be expected for brickwork. A large part of this came from the fact that earth avoided ‘the problem of how to build without bricks, and indeed without mortar’, and ‘equally important, as far as possible without the vast cost of transporting the heavy material of the house from one quarter of England to another.’

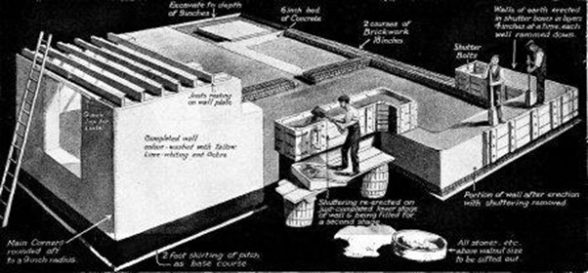

Earth was a way of saving energy and labour, not just cost. The need for transporting materials was eliminated or reduced, and the form of actual construction was relatively simple. Williams-Ellis gives detailed instructions of how the walls of the White Cottage were formed from pisé: refining the earth to remove stones and other unwanted material, pouring it into shuttering, ramming it by hand, hammer-chipping the surface and then applying render. He reckoned that pisé was a quick way of building, estimating that the average worker could build 6ft square of wall in a day.

Williams-Ellis was writing at a time when contemporary phrases such as ‘energy efficiency’ and ‘carbon emissions’ did not really exist. More often in the 1910s and 1920s, people talked about ‘economical’ and ‘labour-saving’ processes. But much of Williams-Ellis’ approach is concerned with reducing the impact of construction on the environment. For instance, he stressed that earth construction was more efficient than labour- and energy-intensive bricks, which needed to be extracted, moulded, fired and transported before being laid. In contrast, the soil used for the White Cottage was taken directly from Newlands Corner, requiring no firing or transportation.

Williams-Ellis championed earth construction as it used local materials, labour and knowledge. Certainly, this was true in certain parts of the country, such as Devon, where cob was used historically and local builders were familiar with them. However, he was also the first to admit that it would not work everywhere. Rather, he advocated learning from vernacular architecture to find the most efficient form of building for a particular region, saying jokingly:

Formerly, he who wilfully carried bricks into Merioneth or the Cotswolds, or slates into Kent or ragstone-rubble into Middlesex, was guilty of no more than foolishness and an aesthetic solecism. Under present conditions such action should render him liable to prosecution and conviction on some such count as ‘Wasting the shrunken resources of his country in a time of great scarcity’ … in that he did wantonly transport material for building.

Earth construction was also about creating homes which were both efficient to heat in the winter and cool in the summer. Williams-Ellis gives various examples from around the world, including India, Australia and South Africa, to demonstrate the insulating properties of earth construction and its versatility in different climates. In Devon he noted that locals would dread leaving the traditional cob houses for the new brick ones – the latter were cold in comparison.

The White Cottage was completed in time for the book’s publication. The external faces of the cottage were ‘finished in several different ways with a view to determining the most durable and economical form of epidermis.’ How these different finishes performed over time, or even the house as a whole, is not so well documented. It seems to have been largely forgotten in the years after its completion. The cottage was much altered in the 1980s when it had new windows put in and the walls were either rebuilt or had new brick facing added to the pisé core. The idea of pisé did not fare much better, with most of the house building of the interwar period dominated by brick and concrete. Rammed earth has occasionally been touted as a new sustainable construction material for the future since, but it has never become mainstream.

While Williams-Ellis saw in pisé a solution to the housing crisis, it was not a solution for everything. At its core, pisé was an artisanal solution to an industrial problem. It relied on traditional methods to fix problems that perhaps may not have been new, but at least were found at an ever-increasing scale. For instance, he does not give much consideration to the environmental ramifications of extracting earth for construction, especially if this was done en masse to resolve a housing shortage. While pisé construction as described by Williams-Ellis may have been cost- and energy-efficient for rural housing, it was perhaps the lack of industrialised earth extraction and processing that prohibited rammed earth from becoming widespread in the suburbs of the 1920s.

Nevertheless, the White Cottage reminds us that traditional buildings can be energy efficient in their own way and that we can learn from, and experiment with, traditional construction. Traditional architecture has frequently adapted to local conditions with low-tech solutions, using local materials developed over centuries of experience. It has proven that energy-efficiency can be entirely in harmony with the local climate and context.

James Phillips is a planning officer at the London Borough of Richmond-upon-Thames, and a writer and researcher of planning and architectural history.

Building of the Month is edited by Joe Mathieson; an Architectural Adviser at the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, writer and C20 volunteer.

For pitches, or to discuss ideas for entries, please contact: joe@c20society.org.uk

Postscript:

After publication of this piece, a reader of the column noted that the Newlands Corner bungalow is part of a bigger story, namely the adoption of rammed earth by the Ministry of Agriculture as the official building policy for the post-WWI agricultural settlement programme. The flagship scheme of the programme was the Amesbury settlement of 1919-1920. The driver behind the programme at the Ministry of Agriculture was Lawrence Weaver, and William-Ellis was one of the architects recruited accordingly. For further reading see Mark Swenarton’s piece, ‘The rammed earth revival: technological innovation and government policy 1905-1925’ in ‘Construction History’ 19 (2003).

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.