This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

October 2015 - Furniture Industry Research Association, Stevenage, Hertfordshire

By Geraint Franklin

The Furniture Industry Research Association (FIRA) was a direct result of the government’s measures for post-war reconstruction. The 1939-45 war led to a national reconfiguration of the furniture industry, redeploying labour and materials and requisitioning factories and warehouses. Rationing extended to ornament as the utility furniture scheme introduced approved designs in an austere Arts and Crafts vein. Government control over manufacture extended into peacetime to meet domestic consumption and revive the critical export market. Drawing upon the pre-war model of the Cotton Board, development boards were founded to restructure, rationalise and regulate industry. In the popular imagination such establishments were peopled with white-coated boffins, presiding over humming and whirring machinery, symbols of a modernising, technocratic Britain.

The Furniture Development Council (FDC) came into being on New Year’s Day 1949. Represented by government, the key firms, unions and employers, it was financed by a compulsory levy on industry. The initial director was Jack Pritchard (1899-1992), a larger-than-life figure whose firm, Isokon, manufactured bent plywood furniture designed by Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer and Wells Coates. Pritchard’s emphasis on research and performance testing led to the formation of the Furniture Industry Research Association (FIRA), which inherited the FDC’s research and technical advice functions, scattered across a number of sites. Purpose-built premises were judged necessary, and a site was found in Bethnal Green, at the heart of the East End furniture industry. ‘What better?’ replied Pritchard’s opposite number in the Forest Products Research Laboratory; ‘It will be in the true Hoxton Square–Shoreditch Road tradition. Will you have having a shell roof?’

Having unsuccessfully invited the London County Council architect’s department to design the new buildings, Pritchard in September 1959 was put in touch with John Partridge. It was at the LCC housing division that Partridge met Bill Howell, John Killick and Stan Amis and the four designed the Roehampton Lane (Alton West) estate. Howell and Killick left to teach and start a kitchen table practice, joined by Partridge for the Churchill College competition. Their entry, placed second, was widely published and soon led to commissions from Birmingham University and St Anne’s and St Antony’s colleges at Oxford.

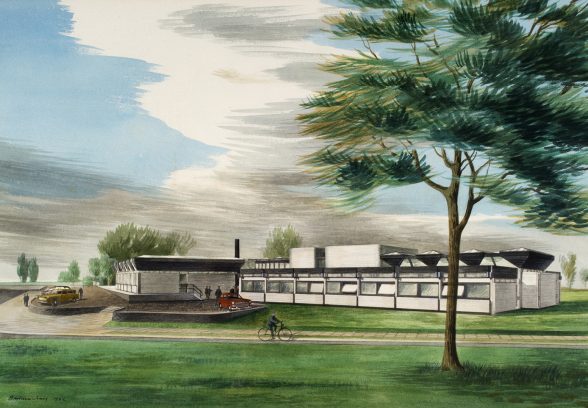

The need to segregate desk work from what Pritchard called ‘the Heath Robinson type of equipment’ led to a wedge-shaped circulation core which mediated between a square workshop block and an oblong research and administration wing. Linear ducts housed within paired downstand beams contained overhead services. The bristling concrete frame was loaded up with timber windows with radiused corners, a chunky wraparound balcony and spiky roof lights, the last recalling HKP’s Churchill scheme. The design was an at advanced stage when, faced with intractable planning problems, the FDC decided to pull out of Bethnal Green in favour of an industrial estate at Stevenage new town.

At this point, Pritchard assembled a building committee: Oliver Lebus of the furniture manufacturer Harris Lebus, John Hard of the British Furniture Manufacturers’ association and the structural engineer Frank Newby. The merits of a single open-plan space were debated, but Partridge feared that the different functional requirements of workshops, laboratories and offices would not fit happily together under one roof. He recommended a horizontal array of independent parts, each capable of outward expansion. They were accessed from a circulation stem, kinked at the main entrance and rising to a first floor council chamber.

The site was overlooked on three sides by roads including a raised dual carriageway, so the mostly single-storey structure had to look good from above. With structural engineers Alan Harris and James Sutherland, Partridge designed a series of triangulated, long-span trusses of tubular steel and pine. Less dazzling but more richly detailed than its exact contemporary, the Leicester Engineering workshop, the FIRA roofs are related to the lightweight gymnasium Partridge designed for Acland Burghley School in north London. ‘I did register anxiety about the roof’, wrote Pritchard in August 1962, fearing for his committee. ‘I don’t want them to get alarmed and feel it is going to be an extravagant and expensive building, which it must not be’.

The building was completed in June 1964. Although an atypical commission – HKPA were by then known for their higher education work – the FIRA headquarters demonstrates the firm’s instinct to disaggregate the brief into a cluster of cells, employing rigorous detailing to resolve the tricky junctions and create a unified whole. The variegated volumes are bound together by a consistent palette of white-painted brick, black timber and hardwood joinery, while a dwarf wall in shuttered concrete funnels cars and pedestrians. Over the prismatic roofs rise the council chamber and its subsidiary spaces, expressed as rounded brick pods. The cranked entrance hall, intended to impress visiting delegates, is dominated by a laminated timber stair which dips and rises mid-flight to accommodate a landing, flanked by low aisles with pine trusses.

‘We are new in the laboratory field, having been raised as housing chaps’, Howell confessed early on, and Pritchard fixed up several reccies to recent research laboratories. John Partridge described one such visit to the Shirley Institute in Manchester: ‘I did have the feeling that the building was very dead internally and this may have been partly due to the fact that everything was concealed and all the surfaces were flat and unmodelled. I think it would be possible [to] make the [FIRA] building much more alive with perhaps most of the services showing although designed into the overall scheme of things.’ The idiosyncratic character of FIRA building may in part be a reaction to these sterile prefabricated structures. The reference to services is intriguing, prefiguring high-tech thinking, but it is the use of manifest structure to unify and animate the interior spaces that prefigures HKPA’s subsequent work. 50 years on, FIRA is still going strong, and the complex has been expanded in every direction (as anticipated), but it is the top-lit workshops and labs that remain the most intact and uplifting spaces.

Geraint Franklin is an historian with Historic England. He is currently writing a book on Howell Killick Partridge & Amis in the C20/Historic England monograph series, blogging along the way at https://howellkillickpartridgeamis.wordpress.com/.

Authors of books in this series need to raise £5,000 to support publication. Thanks to some generous donors, Geraint is already over half way there, but if you would like to help ensure his book makes it into print you can donate here. Any donation, large or small, will make a difference and will be gratefully received.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.