This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

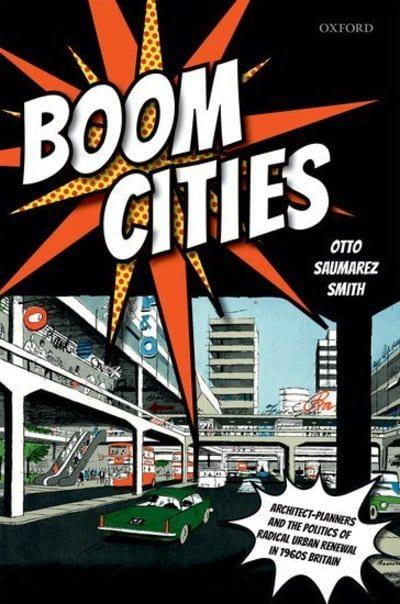

Boom Cities: Architect-planners and the Politics of Radical Urban Renewal in 1960s Britain

Otto Saumarez-Smith (Oxford University Press, 208pp, £65)

Reviewed by Rosamund West

If ever you could judge a book by its cover, it is Boom Cities: the pop art explosion and speech bubble capture the euphoria of 1960s city centres. Such developments have not been the subject of much academic research; as Saumarez Smith explains, ‘The shopping centres of the 1960s are part of a banal, everyday modernism that is invisible and unloved. Whether through snobbery or puritanism, architectural historians have tended to ignore shopping centres.’ Boom Cities moves on the familiar post-war story of the Welfare State, relating the role of private enterprise, political parties, and economic ups and downs.

Admittedly, city centres of the 1960s can be a hard sell: we all know the adage that planners did more damage to Britain’s towns and cities than the Luftwaffe. Of course, Saumarez Smith refers to this, but shows us that the truth is far more nuanced. His book does not completely ignore the view that these 1960s professionals were too quick to demolish too much of our urban fabric. He explains the reality of spaces not being used as intended, the blind faith in the car, and the impact on both the environment and the people who use it of an area changing beyond recognition in a short space of time. There is a most striking instance of this, reproduced in a Gordon Cullen illustration of the area beneath a motorway. It is beautiful, but the 1960s optimism of how lovely the underside of a motorway could be now seems absurd.

While many towns and cities, and many individuals, local authorities and firms are discussed, in two of the chapters he focuses in detail on two practitioners. Graeme Shankland was nicknamed the ‘butcher of Liverpool’ by Raphael Samuel, but Saumarez Smith unravels the two-dimensional image of the architect-planner as an unthinking, uncaring ‘butcher’ by analysing individual schemes as well as emphasising Shankland’s complex relationship with renewal. His interest in preserving Victorian buildings goes against this stereotype. The other, Lionel Brett, is fascinating as a member of the architectural establishment who wrote about it from the inside (in A Broken Wave). His writing shows that much of our city centre development in the 60s was carried out by a very small, elite group.

Refreshingly, this book avoids a London bias: a whole chapter is dedicated to Blackburn in Lancashire. The towns of the North West provide the perfect backdrop for how the politics of urban renewal played out on the ground, and the book really captures the period and the characters involved. Beautiful contemporary illustrations show how Blackburn had everything we associate with developments of the time: the segregation of pedestrians and traffic, the elevated walkways and the ubiquitous clock tower.

Once again our centres are morphing to the tune of developers and gentrification. What will future architectural historians think of our cityscapes, and our assumptions about how they should be used and by whom?

We are still populating our book review section. You will be able to search by book name, author or date of publication.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.