This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

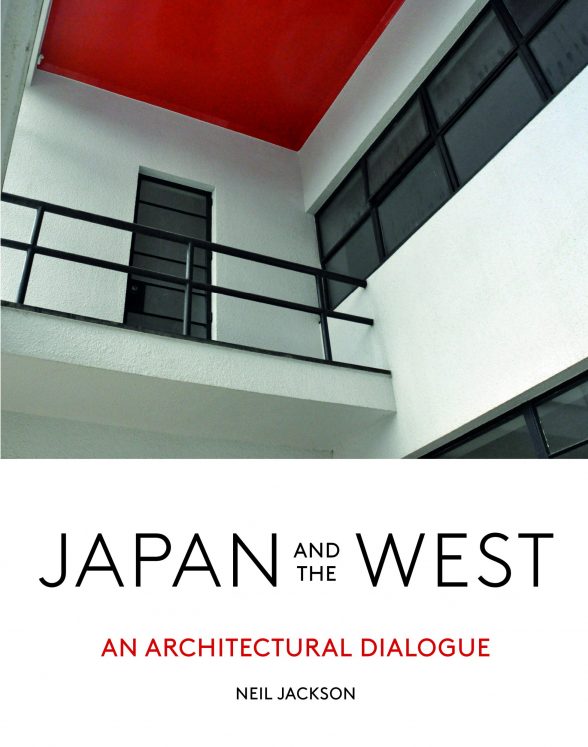

Japan and the West: An Architectural Dialogue

Neil Jackson (Lund Humphries, 416pp, £55)

Reviewed by Andrew Saint

Feb 2018

Japan and the West: An Architectural Dialogue is an heroic book, packed with information and insight. If it’s perhaps more of an encyclopaedia than something to be read through in its entirety, Neil Jackson wears his erudition lightly.

The topic, too, is a vast one. Politics, trade and contested theories of art impinge on every portion of Jackson’s narrative, but he sticks to architecture as tightly as he can. He goes right back to 1608, with the trading outpost established by the Dutch East India Company at Hirado Bay, then shifted to the nearby island of Dejima. Through that narrow conduit a trickle of curiosity, naïve borrowings, misunderstandings and mutual bafflement began.

After 1854 the trickle became a flow, as the Japanese sent ‘ambassadors’ to the West. In the other direction, merchants and travellers piled in, succeeded by the architects who are Jackson’s primary concern. It’s clear Japan did not get the best of the bargain. Britain’s main export was Josiah Conder, a worthy fellow who got western architectural education going but was a pedestrian designer. From Germany came Ende and Böckmann, who (with help from one Hermann Muthesius) built the Imperial Diet, a clodhopping piece of Wilhelmine classicism. And so on. If Japan did well to avoid being colonised, the impression given here is that it got clobbered with a raft of alien buildings lacking the consistency that British, French and Italian colonies enjoyed. Nor did Conder’s pupils inject much individuality into the styles they assimilated.

The story up to 1914 occupies almost half the book and is frankly sometimes a bit of a grind. The liveliest chapters deal with traditional Japanese principles of design, construction and domesticity – the modularity afforded to houses by the standard dimensions of the tatami mat, the cheap thin walls, flexible partitioning, low windows, etc. Although walls and partitions were light, roofs were often heavy and complex, so that houses seem suspended from above – a feature that flat-roof Japanophile modernists chose to ignore. There are briefer discussions of high-rank buildings like the Shinto shrine at Ise, where identical temple designs have been rebuilt century after century. Katsura, the famous imperial villa outside Kyoto venerated by Bruno Taut, Gropius and countless others, is often referred to but not properly illustrated, and what is already a long book feels as if it needs to be even longer to be complete.

From Frank Lloyd Wright onwards, things hot up. Wright was seriously interested in Japan, as few western architects have been. The connection has been thoroughly studied, so Jackson has just to summarise. The first truly interesting architect to settle in Japan, the pragmatic Czech-American modernist Antonin Raymond, there from 1921, gets shorter shrift, tucked in under Le Corbusier’s wing. Bruno Taut is better served. He visited Japan as an exile in 1934–36, and was enthralled. What a shame he did not live to put its lessons to use! Jackson also gives space to Wells Coates, who never forgot his years in Japan and mimicked Japanese arrangements in his flat interiors.

Post-war, western architects tended to visit Japan once, come away and claim to understand. Le Corbusier, vastly influential through the Japanese assistants who returned home to spread the faith, behaved typically. For his one building there, the National Museum of Western Art, he ignored the brief with a design that was far too big and had to be sorted out by local acolytes. The Smithsons returned with fuzzy insights to add to their blend of priestly dogmas for berating Europeans and Japanese alike.

In the end the unflinching originality of the post-war Japanese architects themselves, Kenzo Tange, Arata Isozaki, Takamasa Yoshizaka and others, is in striking contrast to the too-often winsome assimilation of Japanese design traditions in the West. That ruthlessness extends to the Metabolists of the next generation, whom Jackson juxtaposes with Archigram, and also to post-modernism. How could they be so bold? Much must have to do with the devastations of WWII and the embracing of fashion. Intangibly different from the West, it is hard to say just what in top-flight modern Japanese architecture derives from the old traditions.

Jackson tries to sum up the national architectural strengths in terms of Ma, a near-equivalent to the western-modernist concept of space. But he also quotes Kisho Kurokawa: ‘The Japanese way is to mix everything … Our whole tradition is [one of] flexibility and change. There is no real opposition to progress here because we do not decide what is right and what is wrong, or what is good and what is bad – that is a very European way of thinking. What we do is to separate them but accept both.’

We are still populating our book review section. You will be able to search by book name, author or date of publication.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.