This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Image credit: Orms

This year’s London Open House festival takes place between 13 – 21 September 2025. Here, our new Head of Casework Laura Mark picks ten of the best twentieth century buildings to see, many of which C20 Society has had involvement with through our casework and campaigns.

Image credit: Hagen Hall

Pine Heath

37B Gayton Road, Hampstead, NW3 1UB

C20 Society was recently given a tour of the refurbishment of this Hampstead town house by its architect Studio Hagen Hall. Originally designed by the South African architect Ted Levy, Benjamin & Partners during the late 1960s, Pine Heath, is a five-storey development of five townhouses inspired by Cape Town’s coastal developments. Retaining many of the house’s original mid-century features, Hagen Hall has completed a significant and energy sensitive refurbishment which involved replacing the original 1960s windows, adding insulation to the concrete walls, and installing solar panels and an air source heat pump.

Image credit: Stanley Picker Trust

Picker House

Kingston-Upon-Thames, KT2 7HX

The Picker House was completed in 1968 by Kenneth Wood and was designed to provide Stanley Picker and his partner with a modern private home where they could live among their art collection. The house is impeccably conserved and features the original Conran Group interiors and artworks by several notable artists.

Image credit: The Modern House

Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate

Flat 85b, Alexandra Road Estate, Rowley Way, Camden, NW8 0SN

Always a favourite to visit during Open House, the 1978 Alexandra Road Estate was Neave Brown’s seminal work and is widely regarded as one of the finest examples of public housing in Europe. Listed at Grade II* in 1993, Alexandra Road was the first post-war housing estate to be listed and at the time was the youngest and largest scheme to be listed. Covering seven hectares, the estate includes 520 houses, a community centre, shops, a pub and a school.

Image credit: Open House

80 Mallard Place

80 Mallard Place, Twickenham, TW1 4SR

Mallard Place is the last SPAN development carried out by the influential design partnership Eric Lyons and Ivor Cunningham. Completed in 1982, the estate which fronts onto the Thames, includes two apartment blocks of one and two-bedroom flats, 45 townhouses, moorings, and a swimming pool. The estate won a Housing Design Award in 1985, five years after Lyons died and is noted as ‘an irresistible higher density model.’

Image credit: Loreta Tale

St Mary and St Joseph Roman Catholic Church

Upper North Street, Poplar, E14

Named as one of the top 10 modern churches in the UK, St Mary and St Joseph’s replaced a Victorian church that was destroyed by bombing in World War II. Designed by Adrian Gilbert Scott, it was built as part of the 1951 Festival of Britain, when Lansbury had been chosen as the site of the ‘Live Architecture’ Exhibition. The exhibition employed some of the leading architects of the day to build projects illustrating the key new ideas in architecture, town planning and construction with the intention of leaving a permanent legacy of buildings.

Image credit: Historic England

Greenside Primary School

51 Westville Road, W12 9PT

This primary school is one of just two school’s designed by Ernő Goldfinger. Opened in 1952, the school was inspired by the optimism of the 1951 Festival of Britain and the need to create a better Britain after the Second World War. The school, which is now Grade II*-listed, was built using a pre-cast concrete system that allowed it to be constructed in just 24 working days. The school’s foyer has an exceptional mural commissioned by Goldfinger and designed and painted by Gordon Cullen. After languishing behind a curtain for more than 20 years, the mural was recently restored after a campaign by the ‘Friends of the Greenside Mural.’

Image credit: Richard E. Pickvance

Blackheath Quaker Meeting House

Lawn Terrace, Blackheath, SE3 9LL

Believed to be the only concrete Brutalist Quaker Meeting House in Britain, this building was designed by former C20 President Trevor Dannatt and completed in 1972. The standout feature of this building is its roof. A collaboration between Dannatt with engineer Ted Happold, the roof structure is a combination of timber in compression and steel rods in tension creating a column free space beneath. The building was Grade II-listed in 2019, following Historic England’s thematic review of Quaker meeting houses. It also featured as Neil Bingham’s Building of the Month back in May 2019.

Image credit: John East

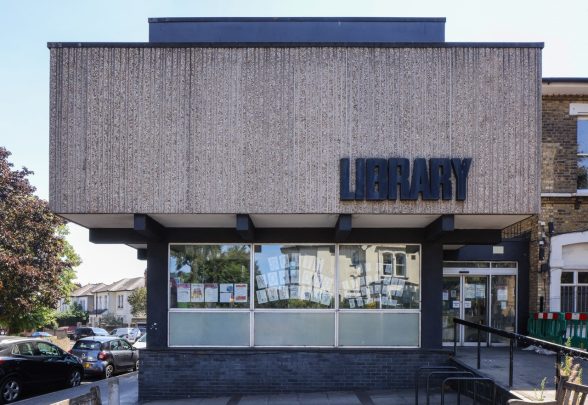

South Norwood Library

Lawrence Road, South Norwood, SE25 5AA

Built in 1966-68 by Croydon Architects’ Department under the lead of Hugh Lea, South Norwood Library is highly characteristic of the 1960s and Croydon’s development boom. Its exterior features the original 1960s ‘LIBRARY’ sign in a Gothic bold condensed font and oversized bronze lettering, mounted on the building’s concrete façade. The C20 Society nominated this building for a prestigious Architecture Today Award, recognising ‘Buildings that Stand the Test of Time’ back in 2023.

Image credit: Selina Kassam

The Ismaili Centre

1-7 Cromwell Gardens, South Kensington, London SW7 2SL

Designed to symbolise ‘the physical representation of Islamic values’, when it opened in 1985 Hugh Casson and Neville Conder’s Ismaili Centre represented an evolution of the practice’s British modernism. Taking up a prominent position on the corner of Exhibition Road, the building is wrapped with a thin skin of polished granite, which has been ‘flame-stripped’ to provide what Concrete Quarterly described as ‘a certain sparkle when seen from the pavements.’ Shahed Saleem chose this as his Building of the Month in January 2014.

The Standard Hotel

10 Argyle Street, Camden, WC1H 8EG

This reimaging of the 1974 former Sydney Cooke-designed Camden Town Hall annexe into a hotel is a great example of how a building can be transformed while retaining its original character and features. Orms proposed a scheme which reused the existing Brutalist building instead of demolishing it – one of the only competition entries to do so. They retained the original concrete frame and precast facade while adding a three-storey glazed extension to the top accessed by a new red lift inspired by London’s red buses. They do a great Negroni too – and if you manage all ten buildings on the list, you definitely deserve one!

Image credit: John East

Twentieth Century Society chair, Hugh Pearman, recently met up with Thomas Heatherwick at his King’s Cross studio, invited in to discuss his attention-grabbing Humanise campaign with its criticism of ‘boring’ postwar buildings and ground rules on how to make new buildings more engaging. While at the Sunday Times, Hugh was, Thomas reckons, the first national newspaper critic to cover his work, very early on.

As our members will know, C20 is an educational charity and has an official role in the UK’s planning process, campaigning to celebrate and protect the best buildings, places and public art of its period – from 1914 to the present day. That covers the full range of styles. Hugh came armed with a longlist of postwar buildings that the society reckoned fulfilled the Humanise principles. Could they agree on a Top Ten of not-at-all-boring buildings? As it turned out, they compiled an Elevated Eleven. And here, in no particular order, they are.

Image credit: John East

Rural council houses for Loddon District Council, Norfolk, 1940s-1950s. Architects: Tayler and Green

Herbert Tayler and David Green designed 687 houses and flats for this South Norfolk council, mainly for agricultural workers. Tayler and Green made them a cut above by simple means: placing them in companionable terraces, individualising them with different colours and patterned brickwork, grouping them to make little hamlets. Trad with a twist, they were among the first buildings in the UK to be described as ‘post-modern’ as early as 1962.

Hugh liked the simplicity and congeniality of these houses. Thomas applauded the front gardens, eaves, welcoming porches and patterned end-walls. “It feels like they weren’t trying to be too crazily modern. And it’s an urban type, even if they’re not sitting in an urban context,” he said.

Image credit: John East

Central Parade, Walthamstow, 1954-8. Architect: F.G. Southgate

Replacing wartime devastation, this really cheers you up, with its wavy canopy and patterned flank to the corner clocktower with its mysterious sky-room. This is a high-density housing/retail development with a strong civic presence. Stylistically it’s a late example of the Festival of Britain style. It now contains a community workspace, still with flats above.

Thomas: “It’s nice because every town has its shopping parade and we still need our version of that with alternative uses. High streets are where we meet each other. This is celebratory.” Hugh: “It also reminds you of a time when borough councils employed good architects. I’ve always wanted to have a summer party up in that loggia on top.”

Image credit: John East

Christ Church and Upton Chapel, Lambeth, 1959. Architect: Peter John Darvall

More inspired war damage reconstruction: a blitzed Victorian Congregational church on a key junction needed a smaller place of worship by the end of the 1950s. The original tower and spire still exists and the new chapel and hall has this extraordinary entrance screen of interwoven moulded concrete pieces like stretched and bunched fabric, shielding a glass wall behind. The same architect added a modest office building.

Thomas was fascinated by its design ingenuity. “This is tessellation, but it’s three-dimensional. What’s wonderful is that it’s also the windows! It’s a kind of Gaudi-Gothic – some of it’s holding the glass, the rest of it is leaping around for the sake of it.”

Hugh relishes its sheer science-fantasy oddness as a unique landmark: ‘When I see this I think of H.R. Giger’s designs for Alien: organic but other-worldly.”

Image credit: John East

Jesmond Library, 1963, Newcastle upon Tyne. Architects: Williamson, Faulkner-Brown and Partners

Harry Faulkner-Brown’s library for the City Council is an appealing little thing, sitting on a corner in a rectangular grid of Victorian streets. What commands your attention on the street is the circular steel-framed reading room with its zig-zag wall, set in granite paving. The reading room is embraced by a little two-storey building behind. Closed in 2013, it was rapidly reopened and is now run by a committed group of volunteers as both library and community hub. It’s much loved.

“I like the way they’ve used a rectangular wall and window system and by pleating it they’ve made something fascinating, that catches the light as you walk past,” remarked Thomas. For Hugh this little gem is fully in the spirit of all the Carnegie-funded libraries of the early years of the 20th century, each one an individually strong design.

Image credit: John East

Hockley Circus underpass, Birmingham 1968. Sculptor: William Mitchell

William Mitchell was a prolific designer/sculptor famous especially for his highly ornate ‘Aztec’ creations, often commissioned for new buildings. His work is to be found from cathedrals to shopping precincts. Here in Birmingham he ennobled a pedestrian underpass with concrete murals. This is art meeting Brutalism. It’s deliberately designed to be climbable: Mitchell liked public engagement.

Hugh: “It’s a magnificent thing, and I see it has defeated the local graffiti artists. You can’t outdo Bill Mitchell.”

Thomas: “This is bas-relief. It’s a rectangular portal, no great structural gymnastics. Instead it’s creatively telling a story with the relief. Why are more building teams not integrating major artistic people – not just doing door handles and stained glass windows?”

Image credit: John East

BOAC building, Buchanan Street, Glasgow, 1970. Architects: Gillespie Kidd and Coia

Can Brutalism be dainty? Yes it can, in this perfect little shop building, originally an airline office. Not concrete but steel-framed and clad in copper, it has kept its original street frontage. Amiably tough, it sits comfortably between its stone and stucco commercial neighbours.

For Thomas, this meets the Humanise ‘door distance’ criterion. “It doesn’t only look slightly interesting when you step back to the other side of the street. There’s a philosophy here that goes all the way through to the glazing bars around the shopfront.”

Hugh pointed out that it looks carved rather than assembled, and is a classic three-stage composition of separately expressed bottom, middle and top. “They must have been thinking Renaissance palazzo.”

Image credit: John East

Byker Estate, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1972-5. Architect: Ralph Erskine/Arkitektkontor

This colourful and idiosyncratic social housing estate on a steep slope overlooking the Tyne valley kick-started the community architecture movement in the UK. Its Anglo-Swedish architect Ralph Erskine’s team were also planning and landscape consultants. It is a much-loved mix of a long undulating ‘wall’ of flats sheltering a large community of smaller houses.

For Hugh, this is a place that works at all distances – from far away as an object on the skyline, right down to your front porch. It’s a complete city district, “an antidote to tower blocks.”

For Thomas, “it has the confidence to be higgledy-piggedly” – in contrast to the serried ranks of marching blocks often proposed by the disciples of Le Corbusier. “It’s got dirty lines, it’s not pure, it’s not subtle,” he says in approval. He loved the detail of little outside shelves for the small houses, probably for milk bottles.

Image credit: John East

‘Plastic classroom’, Kennington Primary School, Fulwood, Lancashire, 1973-4. Architects: Lancashire County Architects

A redbrick Edwardian school in a Preston suburb sprouted the UK’s first structural plastic building (glass-reinforced plastic, as used in boats). It made use of early computer-aided design in pursuit of a new idea of ‘teaching in the round’. Architects Ben Stephenson and Mike Bracewell also designed it to be human-scale and friendly. It was the only one built of what was meant to be a fleet of these plug-in classrooms, and half a century later it’s in decent condition.

This was almost bound to appeal to Thomas (a former pupil at a Rudolf Steiner school) as a really interesting and clever organic design. “To put all this effort into making child-sized architecture – at a time when it wasn’t freaky that council teams could produce a special building! If it happened today you’d fall off your chair.”

Hugh noted that photos of kids outside the little classroom showed it to be proportioned carefully to suit a child’s eye viewpoint.

Image credit: John East

66 St James’s Street (Target House), London, 1979-82. Architect: Rodney Gordon

This highly sculptural bronze-skinned building is where high-tech meets postmodernism. It’s only a speculative commercial development, but of way higher quality than most of its kind. It’s made to last and looks as good as the day it was built. The chamfered turrets with their latticework of windows at the top and the tepee-like feet to the building’s frame are especially unusual.

“It’s just so lovely and chunky,” said Hugh, but Thomas was rather more analytical. “From a city distance it’s got an unusually different way to do a set-back roof. But the critical thing is at street level, where it’s generous. You feel that someone cared. The child in you makes you want to hide in those split cones.”

Image credit: John East

Contact Theatre, Manchester, 1999. Architect: Alan Short

For several years around the turn of the century, architect Alan Short worked with engineer Max Fordham on naturally-ventilated public and educational buildings where the movement of air in and out becomes the generator of the whole design. He transformed Manchester University’s Contact Theatre, previously a conventional air-conditioned box, into an almost steampunk theatrical fantasy. Only without the steam. It’s clever, fun, and a bit mad.

“I like the fact that he didn’t try to make it look pretty – in fact it looks dangerous,” said Hugh of this pioneering low-energy, high concept theatre.

“No, I wouldn’t say it’s beautiful,” agreed Thomas. “The details don’t tie together to make one story. From a distance it’s got a silhouette that catches your attention, then as you get closer other details emerge. You can feel the care and the effort.”

Image credit: Iwan Baan

Second Home Shoreditch, 2014. Architects: SelgasCano

Our bonus eleventh building brings us firmly into the 21st century – also the territory of the C20 Society. In their first UK project, Madrid-based architects José Selgas and Lucía Cano converted a prosaic former East London carpet factory into citrus-zingy shared workspace, part of a wider shake-out in the office sector which has got quite larky. As part of that they extruded the ground floor with its restaurant and events space out into the street in an orange acrylic skirt. Suddenly an inert vertical street frontage became convivial, colourful and curvy. It didn’t quite make Thomas and Hugh’s Humanised Top Ten list, but it was bubbling under and it got a lot of love.

Jointly published on humanise.org

Image credit: John East

After four and a half fantastic years, I am saying a very fond farewell to C20. I’ve loved being a C20 caseworker – it’s a job that is demanding but hugely rewarding.

As a caseworker, I’ve travelled all across the UK to visit 20th-century buildings and advise on their conservation. I’ve worked on some of the best and most celebrated buildings in the country, including the remarkable 1930s Streamline Moderne De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill-on-Sea, East Sussex; the Modernist Isokon Building in London; the Smithdon School in Hunstanton, Norfolk, an icon of ‘New Brutalism’; and the fantastically robust post-war architecture of London’s Southbank and Barbican estate.

I’ve experienced these buildings in every light and from every angle; I’ve been out on site in the sun, rain and snow, have felt my way through dark basements and clambered up ladders on to rooftops. I’ve got to know these buildings intimately and in a way that few people are able to do.

I’ve also got to know less famous, but no less fantastic, buildings. I’ve worked on a historic early 20th-century eel, pie & mash shop in London; a rare collection of interwar timber rollercoasters at Blackpool Pleasure Beach; an unassuming shed-like timber sauna in a field in Kent once used by athletes in the 1948 London Olympics; and a ‘space age’ 1970s domed leisure centre in Swindon.

Thanks to the generosity of a C20 supporter, I was given the opportunity to travel to the US to participate in the Getty’s International Course on the Conservation of Modern Heritage. It was an amazing experience and taught me a huge amount about the conservation of 20th-century buildings in an international context.

I have celebrated some wins at C20 I’ll always be proud of. Particularly memorable was stopping the demolition of 10 Dorchester Drive, a beautiful 1930s Art Deco house in south London. With support from the local authority and local preservation trust, we got the house listed and saved from the bulldozer. Another big win for me personally was listing the Morris Hall, an interwar public meeting place and home of the Labour Party in my home town, Shrewsbury.

The wins were naturally accompanied by some big losses, which were keenly felt by everyone at C20. These are a painful reminder that 20th-century heritage is too often undervalued and under-protected and that we need organisations like C20 to defend these buildings.

I will continue to advocate for 20th-century buildings and sites in my new role as a Heritage Consultant at Purcell which I begin in mid-April.

I have been lucky to work with some brilliant and passionate people while at C20 including C20’s dedicated team of staff, trustees, volunteers and members. I will miss everyone at C20 very much, but will keep in touch as a friend and supporter.

Illustration by Mark Long

Dear members, followers, and friends,

As the year draws to a close I’m writing to thank you for your support and send you best wishes for the holiday season and for 2025. Reflecting back, 2024 has seen a huge amount happening here, lots achieved and plenty of planning for campaigns, events and publications yet to come.

A year of firsts

We’ve seen a great variety of buildings listed in 2024 – some of which are pictured below – they cover a wide date range; from a traditional 1915 cabmen’s shelter, to the flamboyant Egyptian-style Sphinx Hill – a recent subject of our “Me and My House” article in the C20 Magazine, only completed in 1999 and now the youngest listed building in the UK. We have also had two notable ‘firsts’ – the first listing of an example of outsider art, and the first C21st designated landscape. Our caseworkers have been busy both pushing for this protection, and ensuring that subsequent changes to buildings preserve what’s special about them. A new and increasing challenge has been providing help and guidance to building owners alarmed to discover that their buildings have the now-notorious reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) as part of their construction, and we continue to focus on the best ways to retrofit buildings to improve environmental performance.

We’ve run more overseas members events than ever before (including trips to Italy, Portugal, and Poland) and we reckon that our hybrid-format lecture programme had over five thousand attendees, with nearly 1000 people coming on in-person tours to buildings with us. In 2025, we’ll have a similarly full programme, both in the UK and going as far as Chicago, and we’re taking the big step of appointing a new staff member to join us here in the office in Farringdon and focus on events for the first time. Please spread the word, and if you think you might like to be that person (3 days a week) please apply.

Looking ahead

It is always hard to predict what lies ahead in terms of future threats and casework (I am sure there will be many challenges), but undoubted 2025 highlights will include three new books published with Batsford – 100 Sports Buildings, C20 Seaside Architecture and Cooling Towers, so look out for those, and for events related to each of them.

We’ll also be increasing our fundraising activities in 2025 – building on the successful launch of our Patrons programme this year, and I’m delighted that newly elected trustee Colin Mitchell has been appointed to lead on that with me and our Chair, Hugh Pearman. We have made very modest increases to our subscription rates for 2025, as we want membership to remain accessible, but this means that – vital though your member subscriptions are to our work – core membership fees now only generate approximately 35 percent of our costs.

If you are able to increase your level of support either by becoming a Patron or by donating to the on-going Elain Harwood Memorial Fund, we would be extremely grateful, and promise that your money will be put to very good use.

With best wishes and a Happy Christmas from all at the Society.

Catherine Croft

This week we said a fond farewell to our Casework Director, Dr Clare Price, who’s off to pastures new at the Church of England. Here she shares some highlights and reflects on an incredible 12 years at the Society.

A huge thanks and the very best of luck from all of us Clare!

——————-

So 12 years after I first climbed the stairs in Cowcross Street to join C20 I am off to pastures new. This is a very bittersweet decision for me to make as this has been the best job that I have ever had – something new every day, always learning, finding unexpected enthusiasms, meeting all sorts of wonderful people. Although it is a cliché, it’s fair to say that no two days are ever the same in the job of a caseworker and it’s certainly been a challenge. I’ve loved the site visits – they are always interesting as you get to see buildings from every angle – and often take in great views from the roofs. I’ve engaged in a huge variety of cases and certainly haven’t won them all – well, very few in the grand scheme of things – but every single one has been an opportunity to raise awareness of the amazing range of architecture that we cover.

Listing applications have been very time consuming, requiring detailed research and hours holed up in the RIBA library, some even paying off! Dunelm House in Durham was probably my biggest challenge from that perspective, only achieving listing after two requests for the decision to be reviewed. The team in the office has changed over my time here – we all share our enthusiasms and enjoy team lunches coming up with novel new campaign ideas – but their support and that of the trustees, members and all our marvellous volunteers has been invaluable and kept me going through all sorts (even a pandemic).

Along the way I acquired a PhD – encouraged to hone my expertise in particular C20 area – and as a result have become the in-house expert on churches casework. It is this skill that has led me away from the Society to the Church of England to widen my interest and to explore Cathedrals and Major Churches as a part of their national team. More casework indeed but on a different scale I suspect. I will continue to champion the architecture from our period just as part of a different context. I shall miss everyone at C20 very much, but will remain in touch and come back for events and to support whenever I can!

Dr Clare Price (@InterWarChurch)

Image: Daniel Hambury

Compiled by her friends Bob Stanley (journalist, author, film producer and member of the indie band Saint Etienne), David Trevor Jones, Emily Gee, Paul Stirner and Jon Wright, C20 Society presents a special musical accompaniment to this months Remembering Elain Harwood event at the Southbank Centre.

Spanning punk, post-punk, folk, art rock and african music, the playlist features many of Elain’s favourite tracks and shows her taste in music was just as eclectic as that in buildings! Click the player below and drop the stylus for 3+ hours of sonic exploration.

David Trevor-Jones – Lifelong friend and Chairman of Cinema Theatre Association

Elain was passionately into music. It was what brought us together in Bristol in 1976. She joined the ‘Ents Committee’, the group of would-be musicians, promoters, roadies (and groupies!) that put on concerts in the Student Union. As a major league Union we could get some quite big names, and being there through the dawn of the punk revolution was a fascinating experience for both of us. It changed Elain’s style and outlook as well as her listening.

On moving to London in 1980 Elain started going to gigs at venues such as The Marquee, The Moonlight Club, The Electric Ballroom and The Clarendon (all now long gone). This was the immediate post-punk period that spawned a whole generation of innovative, thrilling music. It also saw the emergence of world music from its narrow niche and Elain dived enthusiastically into African music, especially the East African guitar bands championed by Andy Kershaw and John Peel.

Most importantly, Elain adopted The Fall very early in their recording and performing career, starting a life-long fandom and special relationship with that band and their music. They were undoubtedly her favourite band of all time. Among Elain’s literary works was a contribution to ‘Excavate – The Wonderful and Frightening World of The Fall’, edited by Tessa Norton and Bob Stanley.

Music really mattered to Elain. Before the pandemic she commenced the huge project of listening to her very large record/cd collection in alphabetical order – I don’t know how far she got or whether she completed it. So she did look back as well as forward in her listening but in recent years she pursued a path into electronic and dance music, and necessarily into the soundtracks for SPIN classes. I am not sure that she revisited the music that she was listening to pre-punk, around the time that I first met her, but she did talk about it in an interview with our mutual friend, the music journalist and author Mike Barnes, for ‘A New Day Yesterday’, his definitive account of Prog Rock. I do know that she maintained her commitments to African guitars and to The Fall (though it ceased to exist as a band/project following the death of main-man Mark E.Smith in 2018) and also to the radio show presented by John Peel’s son. Just as Peel Senior inspired Elain’s musical listening from the start and through the decades of his BBC Radio 1 shows, Tom Ravenscroft continued to do so with his show on Radio 6 Music to the end. Elain’s musical taste was never, ever mainstream!

C20 has created the Elain Harwood Memorial Fund to ensure that her invaluable contribution to the safeguarding of Britain’s remarkable modern architecture and design heritage. The fund will help secure the long-term future of our vital casework and campaigns, while offering new opportunities to young people passionate about heritage. If you’re able to give and want to invest in the future of the Society, please click here for more information.

Image: Wilde Fry

As the growing crisis around RAAC concrete in schools and public buildings dominates the national news, Catherine Croft provides a handy explainer on this widely used post-war building material.

Any situation which might cause the sudden collapse of a building is clearly enormously concerning, and the safety of people must be the top priority. There is an urgent need to understand where RAAC was used, to examine whether or not it is now failing in each case, and then work out how best to repair or replace every building which requires urgent attention.

We don’t know yet if any of the schools or other buildings with deteriorated RAAC are ones which are either listed, or ones which may have merited listing in the future, but heritage concerns must of course come second to public safety.

What is RAAC and why was it developed in the first place?

AAC is the acronym for “autoclave aerated concrete”, first developed in the 1920s, RAAC, is AAC with added steel reinforcement-hence the “R” at the front. AAC is a special form of pre-cast concrete, that is concrete made in a factory, rather than cast on site, like the very visible concrete of most Brutalist buildings, such as the South Bank Centre.

By aerating the mix to provide a bubbly structure, which has been accurately compared to an Aero chocolate bar, the overall weight of the concrete is hugely reduced. The aeration is caused by a chemical reaction initiated when water is added to the mix. RAAC is cast in steel moulds and then, after it has set sufficiently to be taken out, it is placed in an autoclave in the factory to increase its strength. This heats it under pressure, a process more like firing a clay brick in a kiln than the normal curing of concrete at ambient temperature.

Unlike standard concrete the RAAC mix only includes small particles, and no larger stone aggregate (the small pebbles or chippings which can give normal concrete much of its character). This means that the individual planks and blocks created are much lighter and therefore cheaper and easier to transport to site and lift into place. They also have other advantages, including better thermal insulation, and good sound insulation.

It has always been understood that RAAC elements have less compressive strength than regular concrete ones of the same size, that is they will crush more easily if a compressive or “squashing” load is applied to them. This will have been taken into account in the initial design process, and there seems to be no evidence that this was not the case in almost all instances. The most common use of RAAC was for beams, used in flat roof and floor construction.

Problems

There seem to be a number of specific types of problem emerging:

Other issues which may be problematic, include flat roofs where extra weight has been added to address problems of water ingress. It will also be crucial to take into account the strength of RAAC when adding additional insulation to a building to improve its thermal performance.

Beyond schools, it seems probable that other public buildings from the same period – like hospitals, prisons, libraries, theatres and leisure centres – may also contain various amounts of RAAC.

It has been said that all RAAC in the country has now “exceeded its design life”. This sounds drastic, but many building components exceed their design lives totally safely. It does not seem to have been proven that all RAAC inevitably crumbles apart after any fixed period of time, and estimating future “design life” when making a component, or building a building, is not a precise science. Research needs to be done on RAAC taking examples made by different manufactures, and used in a full range of building types and locations, with good and bad subsequent maintenance regimes.

Parallels

There may be parallels that can be drawn with High Alumina Cement concrete. This was a product popular from 1950 to 1970, but banned after a few well publicised collapses in the 1970s. Subsequent research has shown that the primary causes of these collapses were poor construction details or chemical attack, rather than problems with the concrete itself, and (as the Concrete Centre attests) up to 50,000 buildings with HAC continue to remain successfully in service today in the UK. The financial cost and the environment impact of replacing concrete can be immense, and no doubt there will also be some heritage buildings lost as part of a sensible and proportionate response to the RAAC crisis. But hopefully further research will be able to pinpoint exactly which sets of circumstances require demolition, and which can be addressed by remedial works and monitoring.

To reiterate: RAAC almost certainly will be found in buildings C20 cares about, but making sure everyone is safe must come before anything else.

Catherine Croft is the Director of the Twentieth Century Society and teaches the Conservation of Historic Concrete course at West Dean College.

Image: Sarah M Lee

As C20’s new Chairman – the respected architectural writer and journalist, Hugh Pearman – takes up the post, Director Catherine Croft sat down with him to discuss his own journey in architecture, the future of conservation and C20, and his priorities in the role.

When were you first conscious of your interest in architecture?

As a student at Durham, where I was studying English with a bit of Philosophy. I was at St Chad’s College, which faces the east end of the Norman Cathedral. So, I was surrounded by medieval and Georgian architecture, but also an amazing mix of recent C20 buildings. The Dining Hall at St Chad’s is by the neo-classical architect Francis Johnson, which I only discovered later, but there was also Ove Arup’s Kingsgate footbridge across the Wear gorge to ACP’s jaggedly Brutalist Dunelm House (now listed), and in the other direction the modern-medieval University library on Palace Green by George Pace. These all date from the same period, early 1960s. I am catholic in the architecture I like, perhaps because I loved this jumble of styles coexisting happily.

Were you tempted to study to become an architect yourself?

Not at all! I never thought about it! I can’t draw or design, I always wanted to write.

You were starting out at the end of the 1970s, a period currently generating lots of casework for C20 Society. What was happening in the world of architecture from your perspective?

Architecture was at an interesting point and not many people were writing about it. It was the time of the death throes of one kind of modernism, and the very beginnings of post modernism. Obviously, I couldn’t see that then, that’s with the benefit of hindsight. But all sorts of interesting things were happening—from the Alexandra Road housing in Camden, to neo-vernacular tithe barn ASDAs, everything seemed up in the air.

Image: C20 Society

And how did you break into architectural journalism?

After uni, I took a graduate trainee place at a firm of trade magazine publishers. I worked on a travel agents’ mag for a while, after which the deal was that I could choose from whatever vacancies were on offer elsewhere. The one that interested me was an architects’ newspaper called Building Design, then edited by Peter Murray. I got to be news editor there, then quit to become an in-house editor at BDP of Preston Bus Station fame. My boss was Richard Saxon. While there I started freelancing for newspapers – the Guardian and Observer among them. Finally I went fully freelance, and was lucky enough to walk into the vacant architecture critic position at the Sunday Times. I thought this could never last, but it lasted 30 years, to the end of 2015. Other freelance work continued, and books started to make an appearance.

But I’d always had a hankering to be an editor as well as a writer, and that opportunity finally came when I took on the RIBA Journal in September 2006, retiring in December 2020. Writing for a professional audience is very different to a lay one. You have to speak in different voices. And we always tried to avoid being institutionalised.

I’ll come on to focusing on C20 – I know that you have been aware of our work for a long time, and very supportive of recent battles, including the alterations to the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery – but how do you think conservation more broadly is doing at the moment?

I am concerned. It feels as if many hard-won gains are under attack. For instance, since my teens I’ve admired the huge achievement of post-war restoration of canals and navigable rivers, but now the money to keep them going has been slashed to a dangerously low level by the Government . Many conservation organisations have an aging demographic, they are still run by those who had fire in their bellies in the 1970s, and they now need to bring in new blood. Plus in architecture there is definitely a culture wars effect, it feels like a time of retrenchment and uncertainty, and with incomes effectively falling it has become politically expedient to look back to an imagined golden past, to the “right sort of old” and 70-year-old Brutalism, say, is for these people not the right sort of old. They prefer antique-effect. Well, the Society is here for the best neo-geo and all other styles since 1914 too!

So what do you think C20 Society’s priorities should be at the moment?

It’s important that C20 should be seen as studiously neutral, not biased in its style choices. That’s already a strength. And we must never be seen to be in opposition to the architectural profession. Architects are our allies, and C20 has long been advocating for retrofit, which is great. We still throw away too many good buildings and we need to promote good examples of successful reuse, such as (since I’ve mentioned it) Preston Bus Station or the former Herman Miller Factory in Bath (now a campus for Bath Spa University). We need to reach out to more architects, get them on board as members and supporters, and encourage them to talk to us more at pre-application stage when they are altering major C20 buildings.

What about current calls for “beauty”, do you think those voices are helpful, and how should we respond?

In the architectural world the word “beauty” has been claimed by traditionalists as synonymous only with their approach. This is plainly absurd – beauty can be apparent in any style or approach, and is both subjective and mutable. Everything can’t be ‘beautiful’ anyway – that’s like saying everything must be above average. What’s wrong with ‘good ordinary’, in whatever style? Architecture needs biodiversity, not monocultures. Hence my evocation of old and new Durham at the start of this. Good design, better materials and good craft skills are of course vital, but they are not the sole preserve of any one architectural persuasion, as the range of styles of twentieth century listed buildings demonstrates. It’s a bit of a febrile period right now but over time, all this will settle down, as style wars always do. Meanwhile, it’s our job to stay alert lest there are unfortunate casualties of the present faddishness.

Image: Roderick Coyne / Alsop Arch

How about C20 Society’s recent broad campaigns? Have you followed them and do you think they are working?

Yes, I’ve been particularly struck by the Department Stores campaign—a great response to “The Death of the High Street”. It’s good to see more developers now coming forward with conversion proposals. And I’m very concerned about the last generation of coal-fired power stations with their cooling towers. Drax near Selby is my favourite, I love the way it is an almost symmetrical grouping and how well it sits in the wider landscape. To see all those great industrial landmarks vanish forever would be tragic.

So what will be your priorities as Chairman?

Fundraising, never easy, has to be crucial—we need to be able to do more of what we do, more professionally, and that means being able to employ more staff, pay them properly and give them the resources to deliver. That includes good design, up to date communications and the ability to call in specialist help when needed (for planning inquiries, for instance, or to challenge dubious environmental claims). I’ll be looking to strengthen the board, and looking at ways to broaden the membership, many of whom are already actively involved: our volunteers are the best! I’d like more large architecture and design practices to join us, and I’d like to find common ground with the best property developers, working with them rather than being thought of as only oppositional.

To an extent we have to work ahead of public taste, identifying the best of the recent past at the moment when it may be at its most unfashionable. The raft of Millennium projects will be coming up to their 30-year anniversaries before too long. What and where will be the first 21st century listed building? This is why our members around the country are so vital. You really are our eyes and ears.

Having sat in already on most of the C20 committees and seen the work going on, I’m encouraged by the way this is fun as well as being a serious business. There’s a real joy, for instance, in our caseworkers unearthing a previously little-known gem of a building, or in successfully heading off insensitive alterations. Often it’s a matter of education, of enthusing others. And we have no shortage of enthusiasts.

Hugh’s most recent book is About Architecture: An Essential Guide in 55 Buildings (Yale University Press), 2023, available to order here.

Image: Wilkinson Eyre

Catherine Croft | C20 Director

One of the most expensive, ambitious and longest running C20 conservation cases the UK has ever seen is finally crossing the finish line. Battersea Power Station closed in 1983 and is at long last open to the public, and I’ve been along to check it out. C20 Society campaigned for literally decades to keep the sadly decaying building in the public eye, to see off numerous highly destructive proposals for the main structure itself, and curb the size and encroachment of the proposed adjacent development on its magnificent setting. We’ve consistently called for sensitive refurbishment and imaginative reuse, for a solution which works with the grain and character of the building, reinforcing its robust character. We campaigned for interim temporary work to make it wind and watertight, to halt decay and buy more time at stages when many felt that restoration was an unrealistic pipe dream. So is it now a triumph? Should it, or could it, have been different or better? And what can we learn from such a long trajectory for the buildings on our upcoming 2022 Risk List?

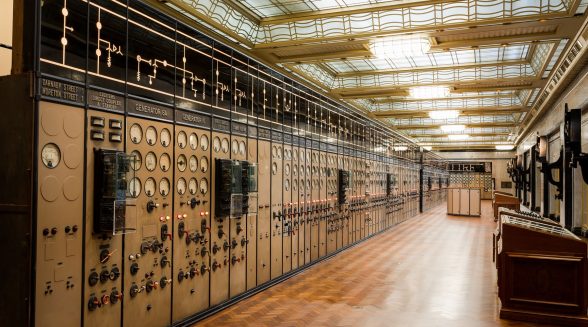

Image: James Parsons

Firstly the positives. Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s Grade II* masterpiece remains a London icon. Both the 1935 Art Deco Turbine Hall A, and the more austere fiancé of the 1950s Turbine Hall B have been restored and are filling with shops. Control Room B will be a cocktail bar, set in amongst the original dials. Working alongside Wilkinson Eyre, Conservation Architects Purcell have over seen “cleaning techniques to reverse the ‘patina of neglect’ present from thirty years of dereliction whilst maintaining the desired ‘patina of age and industry.’ They’ve achieved an excellent balance. The brickwork repairs are exemplary, with handmade replacement bricks sourced from the two firms which made the originals, the overall effect striking a good balance between old and new. Although C20 argued that the case for the reconstruction of the concrete chimneys wasn’t conclusive, the replicas are exact and alleviate all ongoing concerns about maintenance. The space in front of the power station is beautifully spacious with great views of the river, and the new tube link makes it easily accessible.

Image: Wilkinson Eyre

However, how much more we would be celebrating if a more socially beneficial new use for the building itself had been the final outcome, and if the amount of social housing on the site had come anywhere near the levels prescribed for developments in London. The social and cultural success of Tate Modern (Scott’s other London power station, which still remains unlisted) feels like the product of another world, and the comparison takes the edge off Battersea’s success. Battersea is a classy shopping mall, hemmed in by expensive flats which may or may not keep their value. Years of commercial speculation upped the site value and hence the need to maximise profits. Prolonged neglect of the building fabric caused repair costs to soar, and there is still a sense of a better future which might have been.

The lessons for the future must be to look for socially and environmentally sustainable solutions for the restoration of magnificent buildings, and to act fast, to minimise decay and maximise the options for positive conservation.

Image: Wilkinson Eyre

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.