This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Image credit: Sheila Halsall

C20 Society and C20 Cymru are celebrating the fifth Leisure Centre to be listed as a result of our ongoing nationwide campaign, and the first example to be designated in Wales, at Grade II.

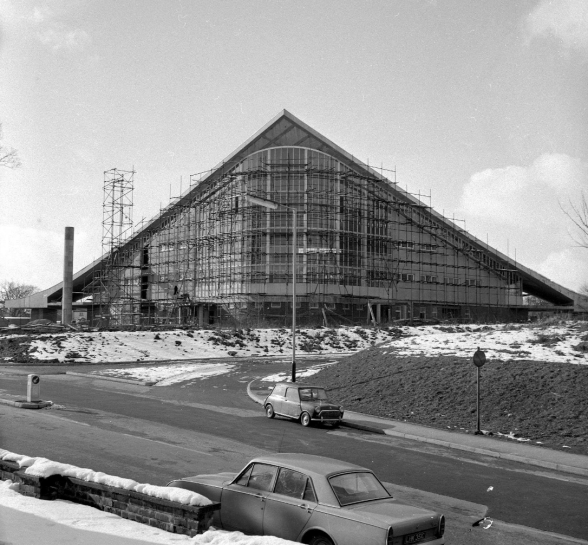

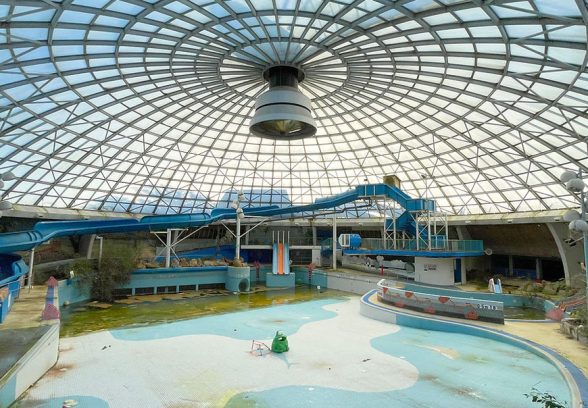

Wrexham Waterworld (1967-70) is characterised by its swooping, manta ray-like hyperbolic parabloid roof of reinforced concrete, which covers a leisure pool, water slide, viewing area, gym and other facilities. It is the key surviving example of an indoor swimming pool of the post-war period in Wales, and displays technological innovation and virtuosity as the first hypar roof in Wales, built on a scale that far exceeded any of its UK predecessors.

Image credit: The Leader / Freedom Leisure

Wrexham Baths, known today as Waterworld Leisure and Activity Centre, was constructed in 1967-70 to the designs of Frederick D Williamson (architect) and Gerald A Williamson (engineer) for an estimated cost of £400,000, paid by Wrexham Corporation using a loan from the Welsh Office. It is believed to be the only hyperbolic paraboloid roof in Wales, covering an area of approximately 154ft x 154ft, and among the largest hypars built anywhere in the twentieth century. Diamond shaped in plan with black brick plinth level, its glazed east elevation looks out assertively over the adjacent A5152 and roundabout, while its west elevation contains a series of barrel-vaulted volumes that step up towards the pointed apex of its roof.

In the late 1990s the building was closed for refurbishment work with a foyer extension and staircases added to its west-corner, and the concrete diving boards replaced by a slide, rapids and a jacuzzi. Fixed spectator seating was also installed at this time. The baths were renamed ‘Waterworld’ and reopened by Queen Elizabeth II on 6 March 1998. Yet despite these alterations, the constituent spaces are broadly the same, and the roof remains the dominant feature, rising and falling dramatically above the pools.

Image credit: The Leader / Freedom Leisure

A listing attempt was first made in 2014, after falling revenue and rising maintenance costs led to fears that the centre could close and face redevelopment. Cadw (the Welsh Government’s heritage body) initially rejected this at assessment on the grounds that the building had already been ‘altered too significantly to be considered as an exemplar building of its type.’ Over the past few years the rarity of early leisure centres has increased, with many key examples like Bletchley (2010) and Crowtree (2013) lost to demolition. Wrexham Council had also expressed long-term plans to reorganise the county’s leisure services and looked into building a new facility elsewhere in the city.

Crucially at Wrexham the distinctive roof and the main elevation to the south-east, the key features of interest, remain as originally designed. C20 Society and C20 Cymru submitted a second listing application as part of our nationwide Leisure Centres campaign in October 2022, the first thematic survey of this building-type. Following a re-assessment, Cadw finally confirmed a Grade II designation for the building in February 2025.

Image credit: Freedom Leisure

C20 Leisure Centre Campaign

The designation for Wrexham Waterworld follows those in England for Doncaster Dome (Faulkner-Brown Hendy Watkinson Stonor, 1986-89), Bradford’s Richard Dunn Sport Centre (Trevor Skempton, 1974-78) Swindon’s Oasis Leisure Centre (Gillinson Barnett & Partners, 1974-75), and Bell’s Perth (John B. Davidson, 1968) in Scotland. All listed at Grade II or Category B following applications from C20 Society as part of our Leisure Centres Campaign.

Leisure centres are places of community identity and an intensely evocative part of our shared social heritage: flumes, verrucas, palm trees, the smell of chlorine, the sound of laughter – this is the backdrop to childhood experiences and families at play. Yet they’re also some of the most architecturally innovative structures of the late twentieth century, combining environmentally controlled spaces with soaring engineering and playful pop imagery. Is there any other building-type that’s as wildly varied and downright eccentric? Space-age geodesic domes, diamond glazed pyramids, castellated forts, brutalist elephants and Moorish postmodern palaces are just a few of the highlights of this idiosyncratic genre.

Some key examples remain from the 1970 and 80s boom in publically-funded municipal leisure centres, others are playful evolutions on the theme from more recent decades, while the exotic continental import of Center Parcs signalled a later shift to a packaged holiday experience. Most were designed around a free-form tropical pool, others focussed on hard courts and recreational sports. All are underappreciated and unexamined buildings in need of our support.

The decimation of local authority budgets over the last decade has already forced many centres to close, with the economic challenges of recent years only heightening the threat they now face. The Covid pandemic, global chlorine shortages and the soaring energy costs have meant that, in the words of Swim England’s chief executive, “Every pool is now at risk”.

Image credit: Jonathan Vining

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.