This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

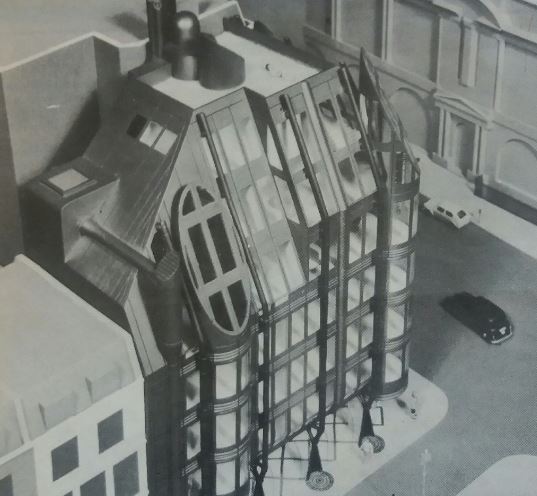

© Architectural Press Archive RIBA Collections (Photographer Charles Martin) 1983

Photo: © Joshua Abbott

May 2021 - 66 St James’s Street (Target House), London

Rodney Gordon for Batir International Architects (1979-82)

On one of the most exclusive London thoroughfares, a building by an architect more often associated with the crafting of mid-century concrete megastructures, blends glossy swagger with engineering precision. 66 St James’s Street (or Target House) was a late career offering from Rodney Gordon (1933-2008) and is unashamedly postmodern.

For those more familiar with Gordon’s adventures in Béton brut, 66 St James’s may appear a stylistic departure. During an intense decade (1960-70) as design director with the Owen Luder Partnership he explored and pushed the sculptural scope of Brutalism, notably at the Tricorn Centre, Portsmouth (1966) and Trinity Square, Gateshead (1969), demolished 2004 and 2010 respectively; one-time gem Eros House, Catford (1963), remains but has been aggressively neglected and overclad. Yet 66 St James’s is in fact a continuation of, not a break from, the thread that ran through Gordon’s career. He described the building as offering ‘total expression of the way in which it is constructed and functions.’ Combining this ethos with a bravado assault to the senses was Gordon’s calling card – and that he mastered materials other than concrete should come as no surprise. The clues were always there.

© Architectural Press Archive RIBA Collections (Photographer Charles Martin) 1983.

Gordon’s electricity substation (1961, Grade ll) designed as part of the post-war redevelopment of south London’s Elephant and Castle is an entirely functional design but its curious location and futuristic envelope has ensured its reputation for prompting the uninitiated to ponder ‘what is that?’ Dedicated to the scientist Michael Faraday, the simple box, suspended, is cloaked with stainless steel panelling (a nod to Faraday’s alloy steels research). It is the great survivor on its urban island, amid mostly inane regeneration. His domestic design, Turnpoint, Surrey (1962, Grade ll), is a delicate work in steel and timber cladding, raised from the ground on dainty stilts, the walls finished the same way, inside and out.

R. J. Worley’s Map House (1900) had been one of the jauntiest buildings on St James’s Street but it was also deemed rational, successfully negotiating its prestigious corner site and providing ‘punctuation in the landscape of the main road at a point where the differences of the building created interest without imbalance.’ (Building, April 1981). Once identified for demolition, the tenor of the advice on its replacement from the Royal Fine Art Commission and Westminster planners was that it could be idiosyncratic in line with the best architectural fancies of the district, but it should heed the disciplined form of Map House.

© Architectural Press Archive RIBA Collections (Photographer Charles Martin) 1983.

The Architectural Review (April 1979) approvingly noted that this counsel had been absorbed by the design team (which included Ray Baum and Laurie Abbott) without dampening down the end result, describing it as ‘imaginative and uncompromising.’ The client, Samuel Properties, was praised for ‘not taking the easy way out’ and ‘hiding their speculative development behind a historicist façade.’ The playful devices used to turn the corner into St James’s Place (cylindrical rocket-like turrets, a gentle gesture to the building it replaced, and a recessed entrance) and the high-quality chocolatey rich materials identified for the façade were praised.

Building magazine’s ‘Building on Site’ (1981) feature recounted how Gordon (and Sally Miller of the RIBA) undertook a no-fuss consultation to further their understanding of the site and to gage reaction to the developing design. Taking a building model to the cleared site, they asked passers-by for their opinions. One gentleman mused ‘I feel it won’t blend in as well as maybe an ordinary square type building would have done’; another, perhaps having an off day, tried to thrash the model with his umbrella. However, others found the design interesting. One optimistic consultee suggested it would ‘brighten the place up a bit, wont it?’ and another found it ‘beautiful, the turrets are lovely’.

© Tom Dyckhoff 2019

Accommodating Gordon’s design on the tight site was challenging. If the adjacent party walls had required shoring up, it would have left no site to build on. Fortunately, one side was found to have an existing steel structure to which connections were welded. The engineers Pell Frischmann explored how the required building form required could be provided. The steel frame above ground was carefully designed to deal with the unusual shapes and high tolerances required for the cladding. The use of bronze anodised aluminium elevations cleverly responded to the eclectic warmth of the dominant stone and brick facades of the area. Gordon described German specialists Gartner as the only firm capable of producing the cladding to his designs – ‘the chamfered roof line to the turrets is particularly difficult to fabricate’, he admitted. That the building embodies this thoughtful collaboration between architect, engineer, and fabricator is significant – it is a rare synergy, the existence of which cannot be taken for granted.

The positioning of the structural columns and overhang of the floors above was a deliberate tactic to increase space and deter later potential for ‘gimcrack shopfitting.’ The presentation of the ground floor windows, with their seamless joints, is enhanced by the brick paving details around the foot of the columns (including circular lights to illuminate the basement). The verticality of the fenestration across the whole building is a respectful nod to its traditional neighbours. The overall effect is one of lush sturdiness (with a touch of sci-fi, a theme common to Gordon’s designs) combined with a streamlined lightness and energy.

© Tom Dyckhoff 2019

Building Design (May 19

Following completion, Town and Country Planning (May 1983) described the building as an ‘exquisite beauty. Generations to come will surely value it as model of just how beautiful a building can be.’ However, The Buildings of England (2003) dismissed 66 St James’s Street as a bit of design frippery. It described it as a ‘shock tactics’ building, a ‘period piece [that is] too pleased with its own cleverness’. Perhaps it is true that we tease the ones we love. More recently, Jonathan Meades in Museum Without Walls (2012) described the design as a ‘metal clad tour de force… novel and inspired.’ Tom Dyckhoff has described the building as his architectural guilty pleasure.

The building today, perhaps even more than on completion, stands its ground as a postmodern intervention. It is glossier than other significant post-war buildings in St James’s but no less effective for it. It acknowledges its context but does not compete. Rather, it shares the space as elegantly as its neighbours. The building also does that rarest of things. It works in long views and at street level, offering angles and shapes which develop as you move towards and around it. Keeping the observer thinking seems to have been fundamental to Gordon’s approach to design.

Historic England declined to take forward an application for listing last year because there is no threat to the building. It would be perverse to wait for such a scenario. In addition to its special attributes, 66 St James’s helps us understand our (in this instance, late twentieth century) architectural story, and ultimately, beyond preservation, isn’t that precisely what listing is for?

For readers interest, a refurbishment of the interior took place in 2015 (it is a mix of office, retail and residential accommodation)

Helen Bowman (@helybow) is a post-war architecture and design enthusiast. She worked in the heritage sector in England for fifteen years. She now lives in Edinburgh and works at Historic Environment Scotland.

The Building of the Month Feature is edited by Dr. Joshua Mardell.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.