This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

July 2019 - Auerbach House, Jena, Germany

Walter Gropius with Adolf Meyer (1924)

by Alan Powers, trustee and former chairman of C20 Society

Much has been said and written about the Bauhaus, not least in this centenary year of its foundation. The best way to judge the Bauhaus is by its products, which are surprisingly diverse so that no single one can stand for the whole 14-year life of a school that enrolled 1250 students. One could do worse, however, than taking the temperature of a house designed by the Bauhaus founder, Walter Gropius, that has been brought back from a degraded condition and is now a much-loved home.

In 1993, Barbara Happe and Martin Fischer moved to take up teaching positions in Jena in the former DDR, the university town famous for its Zeiss optical factory and its associations with the pioneer of evolution, Ernst Haeckel. Soon after, they became the third owners of the Auerbach House by Gropius, which had been subdivided and had become barely habitable. On the positive side, many of the original windows and interior fittings had survived. Barbara and Martin carried out an exemplary repair during the mid-1990s, using the rooms and garden to display contemporary art that they have commissioned.

Gropius’s clients were similar in their engagement in science, society and the arts. Felix Auerbach (1856-1933) was a university professor in Jena, 68 years of age when the house was built, while his wife, Anna Silbergleit (1861-1933), was 63. Both were Jewish but non-religious and this factor had delayed Felix’s promotion in the field of theoretical physics, despite his reputation as a brilliant speaker. Promoters of lawn tennis in Jena and, on Anna’s part, for votes for women in Mitteldeutschland, the couple were also deeply engaged in music and art – Felix Auerbach’s portrait was painted by Edvard Munch in 1906 as a gift from Anna, and it later hung in their new house. Before 1914, they had close contacts with the cultural leaders in Weimar, only 14 miles distant, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, Count Harry Kessler and Henry van der Velde, who was replaced by Gropius as head of the school that he renamed Bauhaus.

Walter Gropius retained an architectural practice during these years, providing informal architectural teaching for the school. Conditions in the defeated Germany were exceptionally difficult, and alternative construction methods were needed. The Auerbach House was built using the ‘Jurko’ block system with breeze blocks with inner and outer walls separated by a layer of ‘torfuleum’ (a kind of linoleum), and concrete floors.

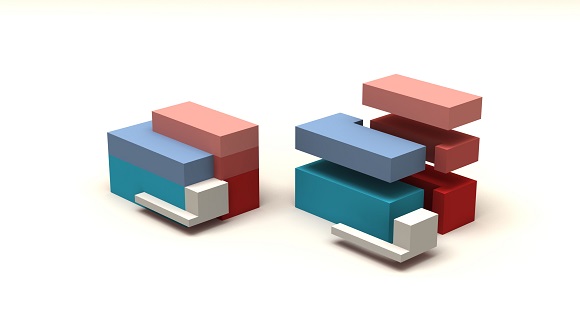

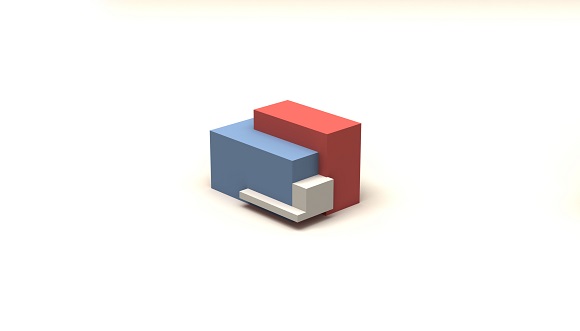

Before this date, the two main houses designed by Gropius in the Berlin suburbs had both been symmetrical in elevation, but with the Auerbach commission Gropius used a design system that he called ‘Baukasten im Grossen’, or giant building blocks, essentially a three-dimensional compositional assembly of interpenetrating volumes as explained in the accompanying images, developed later with the Masters’ Houses at Dessau for himself and other staff. The service functions of the house are denoted by a taller volume to the north that interlocks with the two-storey volume of the main accommodation, with an asymmetrical shift between them. The proportional relationships of elevations and spaces followed mathematical harmonic systems.

Only after acquiring the house and beginning their project did Martin and Barbara discover the significance of its original colour scheme. Although drawings for this by Alfred Arndt (1896-1976) had survived, it had been assumed never to have been executed.

At the Bauhaus school during the early years, colour was a subject of absorbing attention, with several of the teachers encouraging it as a vehicle for imagination and synaesthesia – seeing colours as sounds and vice-versa. The wall painting course devised by Oskar Schlemmer, made no essential distinction between the work of the house decorator and that of the fine artist, other than a greater sensitivity to colour and a willingness to use it ‘constructively’. It soon became clear from scrapes at the Auerbach house that Arndt’s scheme had been carried out, probably by the artist himself with the paint pot and brush in hand, but that variations had been made on the designs. The evidence on the walls guided the restoration, and where information was lacking, for example where all the plaster on some ceilings had been taken down, the surfaces were left white. Nonetheless, it is a beautiful and fascinating experience to move through the contrasting spaces of the house, and challenges many of our assumptions about the emotional temper of Modernism at this time.

While Le Corbusier used similar light tones in his Maison La Roche, Paris (1923-25), they are confined to individual wall planes rather than chasing between walls and ceilings and suggesting subsidiary volumes within the spaces of the rooms. Since the 1970s, the architect Helge Pitz and colleagues began to restore colour to the exteriors of the 1920s Berlin housing estates of Gropius’s contemporary, Bruno Taut, and these come as a dramatic surprise to those familiar only with old photographs. In older books on Gropius’s work, it was often assumed that no colour schemes at all were carried out, reinforcing the common prejudice that the architecture of the Bauhaus and cognate groups was white and grey.

The Auerbach House is sometimes open for visits by groups (including the Bauhaus tour organised every June by ACE Cultural Tours), but the next best thing to a visit is the full-colour book by the house owners Barbara Happe and Martin S. Fischer, The Auerbach House by Walter Gropius with Adolf Meyer, newly revised and translated by David Haney (Berlin, Jovis Verlag, 2018) 978-3-86859-574-1 (stocked by RIBA Bookshop)

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.