This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

December 2022 - Azurest South, Petersburg, Virginia, USA

Image: Calder Loth

Azurest South, Petersburg, Virginia, USA.

Amaza Lee Meredith (1939)

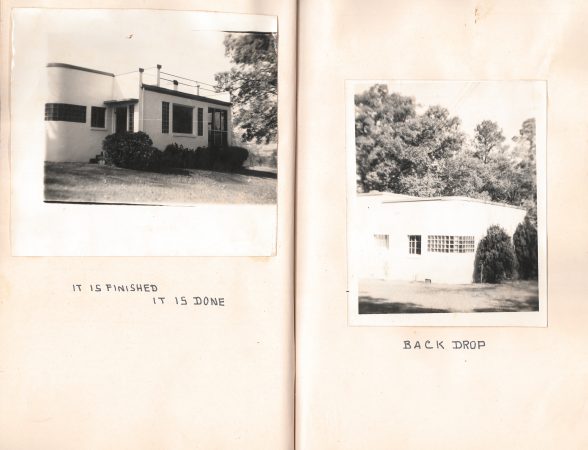

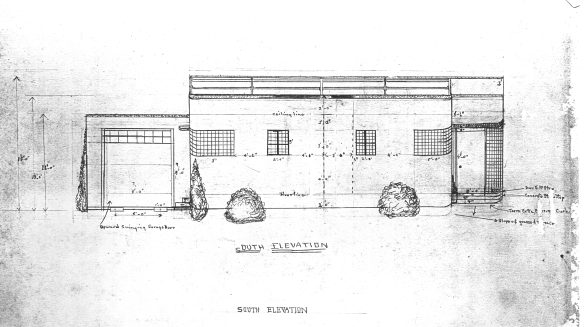

Azurest, so named for the blue-green colour of a summer sky and a sense of peace and calm, is a curious and thrilling anomaly in the canon of modernist buildings. It is a compact cube-like structure made of concrete blocks painted white, with planar walls occasionally punctured by large picture windows and strategically placed textured glass bricks. A flat roof, framed by curved metal coping and accessible by means of a steel ship’s ladder, together with the rounded ends of the building recall nautical features of early International Style structures.

Located on the edge of the Virginia State University campus, this modern single-storey domestic dwelling stands in stark contrast to the traditional red brick and white trim of neighboring Colonial Revival education buildings. Moreover, it appears to turn its back on public scrutiny as it nestles in a dip in topography and is screened by a line of symmetrically planted trees.

Courtesy of Virginia State University Special Collections and Archives.

Courtesy of Virginia State University Special Collections and Archives.

Courtesy of Virginia State University Special Collections and Archives.

Built in 1939 in this enclave of southern traditionalism, Azurest is a singular architectural phenomenon. Its design is avant-garde, its architect stands far outside the margins of the modernist canon. Amaza Lee Meredith (1895-1984) was an African American woman who designed and built this home for herself and her long-term lover, Edna Meade Colson (1888-1985), a fellow female teacher at the all-Black college in Petersburg, Virginia, USA.

Meredith first learned the art of construction and design from her white father, a master craftsman who worked on the decorative Victorian homes of the area. He taught her how to draw, make blueprints, and build cardboard models. Meredith’s mother, a black woman, taught her the importance of education and property ownership as a vehicle to self-sufficiency and social stability in America’s dominant white and highly discriminatory society.

Courtesy of Virginia State University Special Collections and Archives.

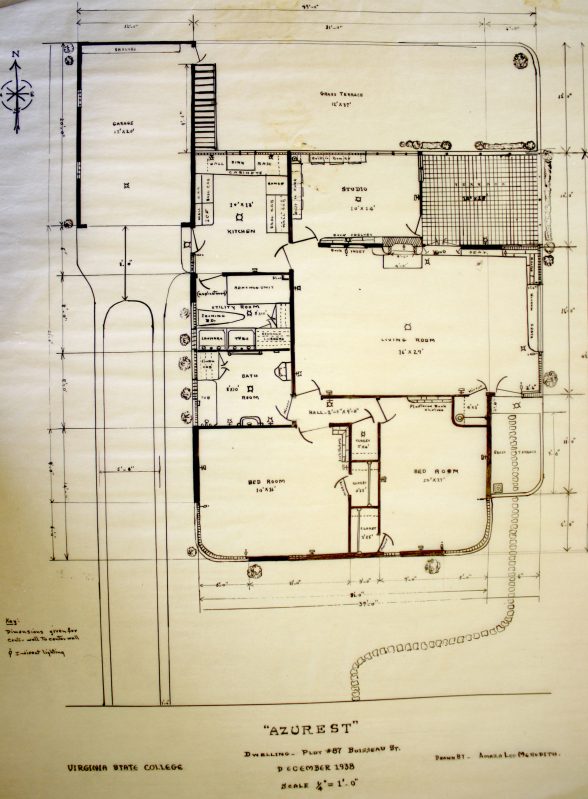

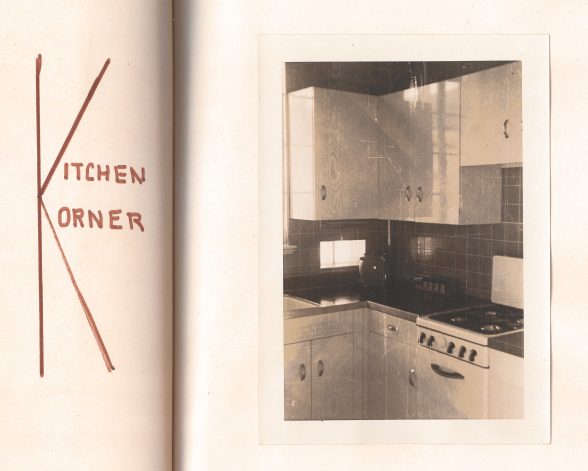

The single-storey building exhibits trends in affordability and efficiency, employing new materials throughout and modern concepts that enable physical and visual connections to the outdoors. From a side road on the main campus a small driveway leads to the rear of the house meeting a carport which accesses the kitchen entrance. Glass bricks brighten the frame of the entrance and form inserts in a corner beside the main window, allowing light to filter onto the countertops. The kitchen is atypical for its time as it is a highly functioning symmetrical space with built-in base and wall cabinetry. Countertops run from the edge of the icebox connecting across base cabinets, sink and stove, to form a unified whole. To the south of the kitchen entrance is a small door that opens onto a utility space, where two large laundry sinks, a drop-down ironing board, and a furnace contribute modern features to create compact self-sufficient living conditions.

The plan of the house centres on a large living room about which the spaces of work, sleep, hygiene, and rest are constructed. Beside the kitchen a studio space has glass bricks along one wall and long windows along another, allowing different measures of light to enter. This space opens onto a sunroom or porch which is enclosed and surrounded on three sides by glass, making it a space that can be occupied during the cooler winter months as well as the oppressive heat and humidity of the Virginia summers. Interestingly this enclosed porch or sunroom also opens visually onto the main living area as if confusing a sense of space and time and allowing greater connectivity across rooms within the building envelope.

Courtesy of Virginia State University Special Collections and Archives.

Courtesy of Virginia State University Special Collections and Archives.

One feature that sets this dwelling apart from the more traditional domestic forms is its equally sized main bedrooms. Two bedrooms form the rounded southern end of the building. They are accessed from the bathroom and the living room through a slip of a hallway. Textured glass bricks puncture the curve of the walls at each side, allowing light to enter the bedrooms, while subtly signaling a space of privacy, cocooned from the outside world.

Throughout the building, thought has been given wherever possible to storage as bookshelves line walls from floor to ceiling and box seats fit neatly along the baseboards beneath windows.

If you only knew the building in plan, you’d rightly imagine it as highly utilitarian, but on seeing the interior you realize this was a space designed to allure, attract, and entice. Surfaces of built-in features are shiny and often brightly coloured. In the bathroom, black and metallic elements offset garishly bright green and yellow walls; in the bedrooms, white painted shelving and mirrors reflect the black lacquer and soft pink or blue of furnishings; in the studio a daybed and side table suggest a space of work but also of pleasure, with light bouncing from glass bricks to shiny metal surfaces and soft satin comforters. Finally, as the only public space, the living room enables multiple views, with a large mirror resting above the curved white painted fireplace, a picture window inviting the outside in, and glass bricks either side adding refracted light to complicate interior shadows.

Image: Jacqueline Taylor.

Amaza Lee Meredith and Edna Meade Colson made this house their home for forty years. It was the first place they had ever lived that was fully their own private space. Meredith used her knowledge of art theory gained from studying at Columbia Teachers College [sic], as well images found in the popular press, shop displays, museums, and galleries of the 1930s to inform her design ideas. She used the house as a laboratory, constantly experimenting with interior furnishings, reimaging it through black and white photography, and adapting the house to suit the couple’s needs, such as turning the garage into a studio space when a third bedroom was needed. On her death in 1984, a year later than Colson’s, Meredith bequeathed the house to Virginia State University as a space for alumni to gather. Until recently, the house has been little appreciated for its singular design and fascinating contribution to the narrative of modern architectural history. Unsympathetic changes were made to the interior and upkeep and maintenance have been sporadic. Today, however, a new understanding is finally coming to bring greater value to what was once thought of as “an odd little place” designed by a woman who bravely fought back against social race and gender norms, and in doing so, pioneered a new way of living in form and aesthetics.

Jacqueline Taylor is an architectural and art historian, working across public practice and academia in the United States. Her current book Amaza Lee Meredith Imagines Herself Modern: Architecture and the Black American Middle Class will be published in 2023 by The MIT Press.

The Building of the Month is edited by Dr. Joshua Mardell.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.