This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

© Margherita Spiluttini

September 2020 - Berani Commercial Building, Uster, Switzerland

Bétrix & Consolascio (Marie-Claude Bétrix and Eraldo Consolascio, with Bruno Reichlin), 1982

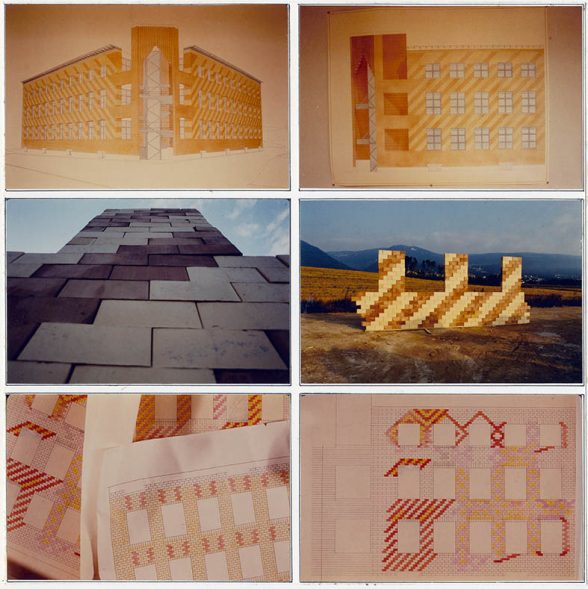

One of Switzerland’s most significant buildings of the postmodern era is located in the industrial area of Uster, a small town outside Zurich. The storage and office building for Berani Kugellager, a ball-bearing manufacturer, completed in 1982, was the second project by the young office of Bétrix & Consolascio, in collaboration with Bruno Reichlin (b. 1941). The office was founded by Marie-Claude Bétrix (b. 1953) and Eraldo Consolascio (b. 1948) shortly after they graduated from ETH Zurich, where Consolascio and Reichlin had worked closely with Aldo Rossi during his tenure there. Rossi’s influence is evident in the way in which history, memory and analogies are present in the project, but there is more: the field of sign theory, a central preoccupation for the architects, played a role as well. The building can be read as an embodiment of 1970s architectural theory – of a wish to challenge orthodox modernism through a ‘semantically active’ formal language, selecting architectural elements for their communicative potential and striving for a richer, more complex meaning.

© Bétrix & Consolascio

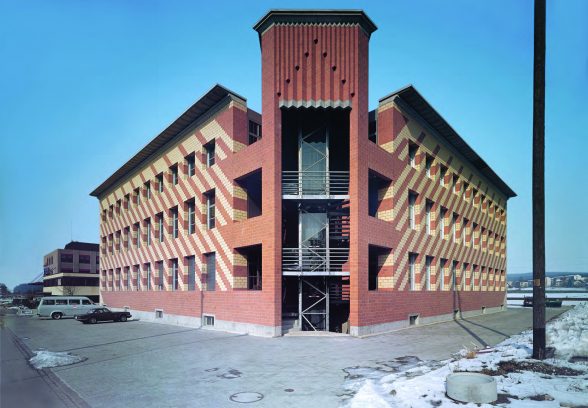

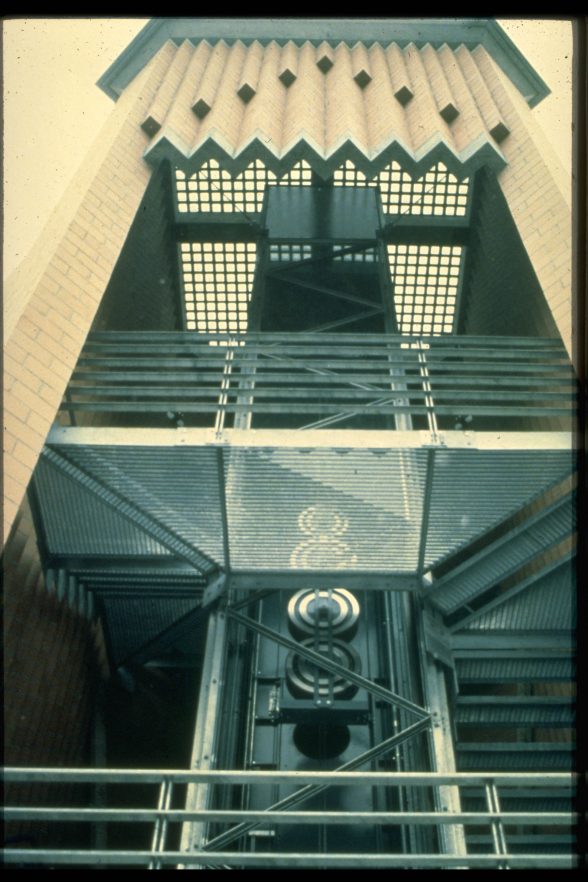

A towering structure, inclined at a 45-degree angle from the street, stands part-attached within the open corner of a brick building. Inside it, in a void stretching over three floors, the main entrance, stairs and lift are visible. Over the void, a rippled concrete beam carries brickwork laid in a three-dimensional, right-angled zigzag pattern, following the geometric logic of the material. The intricate masonry ‘hovers’ over the void like a raised curtain, dramatising the entrance and the vertical access. But the expressive brickwork is also a key to unpacking the larger symbolism of the project: the bricks turn into the physical manifestation of an idea, of a theoretical concept. The real function of the masonry is not constructive – it is the mental images, the cultural connotations that it evokes. Further clues can be found by looking closer at the elevations and the detailing.

© Bétrix & Consolascio

The entrance tower is flanked by two side wings at right angles to each other, covered by diagonal stripes of red and yellow bricks, extending like rays towards the edges. The use of polychrome masonry is a reference to the traditional Swiss ‘factory castles’ – the elaborate industrial buildings of the late nineteenth century in which the colours were used to highlight constructive elements like window arches and corner quoins. The polychrome brickwork is used to evoke the image of the factory, but in an aesthetically modified manner. The diagonals create an abstract, all-over pattern, independent of any constructive logic. The building changes from yellow with red stripes to red with yellow stripes, depending on the standpoint. The optical phenomenon creates a sense of movement that contradicts the solidity of the material, like a built-in objection.

© Margherita Spiluttini

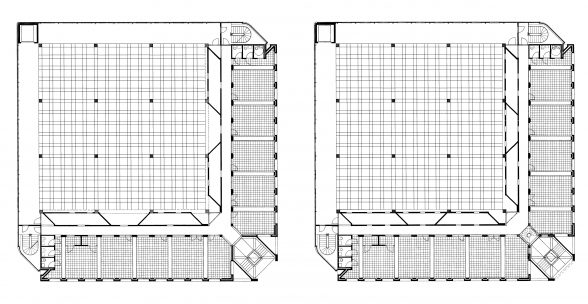

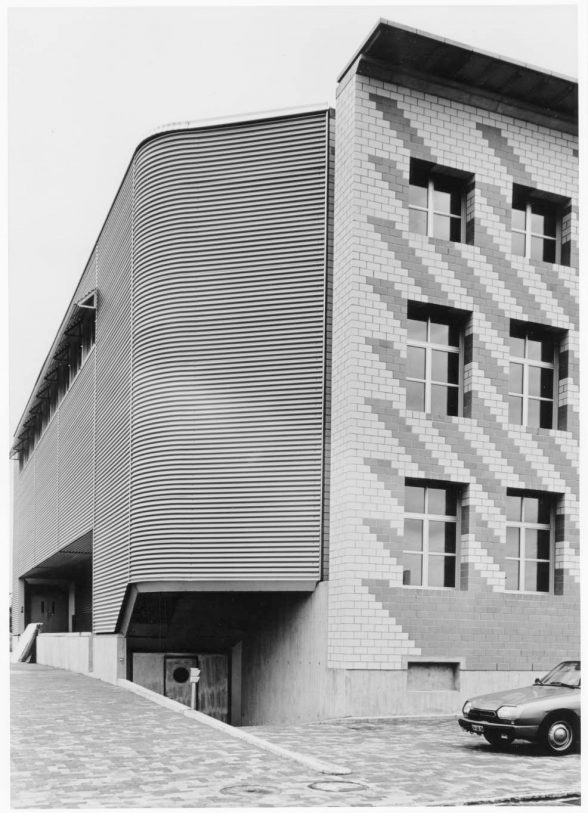

Adding to the levitating bricks and the flickering ornament, a third feature finalises the ‘symbolic’ status of the front façade. As one turns the corner, the warehouse and workshop become visible, with a loading ramp and long horizontal windows, clad with sheets of corrugated steel. There is a striking contrast between the diagonally opposing sides of the building: hung and built, opulent and spartan, humble and historical. When one looks at the floor plan, it becomes clear that the warehouse makes up the large square at the back of the building, while the administrative part in masonry forms an L-shaped angle at the front. It has the depth of a regular office but is hidden by the sweeping curves of the metal sheets at the corners, making it appear to be only a wall – a superimposed layer of masonry, separated by a narrow gap. The gap underlines the façade’s purpose as an ornate enclosure and turns the building into a decorated shed par excellence.

© Bétrix & Consolascio

Through these different articulations – of the prestigious front and the utilitarian back – the architects created one of the most conceptually complex and suggestive pieces of architecture of the era. The approach, simultaneously typical and unique, represents a moment in Swiss architecture shortly before a return to abstract boxes in the 1990s – the industrial shed without its elaborate front. It suggests that Switzerland, known for its strong ties to the Modern Movement, has lived through a development less linear than is often thought to be the case, with significant divergences from the story of modernism as it has conventionally been written. The use of traditional elements as culturally connoted images belongs to an intriguing tendency in postmodern thinking. The building for Berani is remarkable for its sophisticated take on industrial architecture, which combines theoretical content with a skilful display of craftsmanship. Its outstanding attention to detail shows that symbolism and material authenticity are not mutually exclusive. The building for Berani rightly became a sensation, making it onto the cover of the leading Swiss architectural journal Archithese in 1983 and into the architectural history books, and it is likely to be listed in due course.

Frida Grahn is an architect, writer and PhD assistant at USI Accademia di architettura di Mendrisio, Switzerland.

Contact: frida.grahn@usi.ch

Instagram

References

The building of the month feature is edited by Dr. Joshua Mardell.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.