This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

November 2012 - Bispham tram stations, Blackpool

Dr Matthew Whitfield

Building on the success of Allan Brodie and Gary Winter’s 2007 book, England’s Seaside Resorts, English Heritage is continuing its exploration of the significance of seaside towns with a series of shorter projects that focus more keenly on some of the country’s more important resorts. Research has taken place in Blackpool over the last 18 months that has sought to uncover the special genius of the world’s first and largest working class resort, the place that J. B. Priestley hailed as the ‘great roaring spangled beast’ in his English Journey of 1934. The rapid growth of the nineteenth century resort was driven primarily by demand from the workers of Lancashire’s cotton towns surrounding Manchester and their annual ‘wakes weeks’, but by the inter-war period of the twentieth century Blackpool’s appeal had spread nationally and was attracting visitors from as far away as south-east England and Scotland, having become so diverse, large and popular that its position as a centre of the entertainment universe was by then difficult to resist.

Blackpool is primarily a late Victorian and Edwardian town, the result of the explosive growth of the resort that followed the introduction of cheap excursion rail services in the 1870s, but research into the later development of the town has found a story of civic consolidation driven in the main by a series of planned public investments in place of the chaotic spread of buildings and areas that had characterised the leisure industry gold rush of the late 19th century. The key figure in this municipal-led transformation was John Charles Robinson, the Borough Surveyor who, via a number of important projects across a range of planning and building activity by the Corporation, attempted to impose a decidedly modern image on Blackpool as a resort and indeed as a town, with key pieces of infrastructure imbued with a disciplined but ambitious modernistic architectural tone. This was a period of image-making by the Corporation (in partnership with major private concerns such as the Pleasure Beach) where a future was imagined that concentrated on the essence of Blackpool’s attractions – sunshine, fresh air and a subscription to the latest fashions in everything, freed from the mundanity of everyday life. This had always been the Blackpool way, but a new mood took over the resort after the First World War that sought to place an explicitly modern sheen on the somewhat cacophonous Victorian buildings and public spaces that had symbolised the uncomplicated enjoyment of earlier generations – by the 1930s this desire could be summed up in an often repeated term in the local press: ‘streamlined’. To streamline was more than simply to apply a loosely moderne style to paper over the cracks of the ageing resort: to streamline was to attract a higher class of visitor with higher expectations of glamour and excellence, ones who would spend more and perhaps even decide to settle in Blackpool and provide the place with viability as a high rate-paying town as much as a holiday destination.

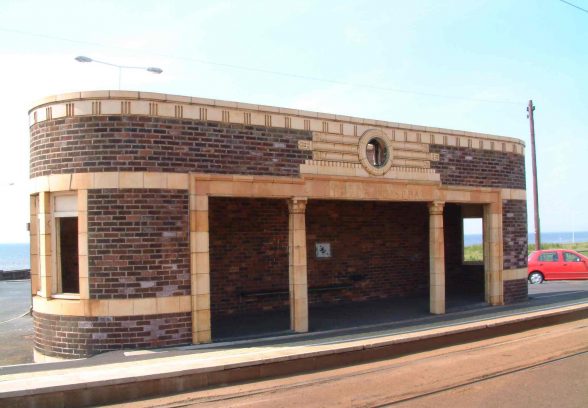

The overall schema of Robinson’s (and the Corporation’s) ambition to make straight all that was crooked is evident in the legacy of transport planning from the 1930s. Two tram stations from the 1930s at Bispham and Little Bispham on the promenade towards the north of the borough act as fragmentary evidence of a largely unrealised but comprehensive scheme to modernise the municipal transport system. Bispham is the larger of the two from 1932, serving the important district centre of Bispham that had been incorporated into Blackpool borough in 1918 and Little Bispham, further to the north and completed in 1935, served an unremarkable but populous suburban extension as speculative housing estates of the inter-war period made their inexorable march along the coast up to Fleetwood. Both stations share the key functions of shelters and public conveniences (for the use of passing promenaders as much as tram users) whilst the larger station at Bispham also had a ticket hall and indoor waiting rooms. This was also the more conservatively designed of the two with the sharp geometry of its horizontal emphasis relieved with restrained classical features and a typical early-1930s fusion of the moderne (with its radically simplified, low-slung pediment) and traditional (a colonnaded central shelter complete with flanking urns). At Little Bispham, a crucial three years further on in the infiltration of modernism into English municipal practice, a smaller but more enticing package was put together by Robinson with a more even combination of the modern and classical. The station was bull-nosed at both ends in a classic device of moderne practice and the use of faience for its columns and other dressings call to mind the best commercial versions of stylised, streamlined classicism from the period. The semi-circular shelter at the rear with views out to the Irish Sea is a surprising but enjoyable part of the overall composition, another rounded elevation which adds much to the sense of a well proportioned, stylishly-realised monument of public service.

Nothing along the tramway or elsewhere in Blackpool was quite on the level of Charles Holden and Frank Pick’s inter-war work in London using explicitly modernist architectural devices and graphical systems to update the infrastructure and services of London Transport, not least in the continued commitment to trams as a form of public transport when their rapid phasing out had begun across much of the country by the 1930s. There are, nevertheless, definite echoes of their approach in the work of the Blackpool Corporation and J. C. Robinson. Modernist experiments were not uncommon in a town with the corporate motto of ‘Progress’, and whilst at least much effort was invested in the provision of multi-storey and (almost uniquely at the time) underground car parking for the judiciously imagined future of private transport, there remained a commitment to the public realm, the role of the Corporation in setting design standards and in providing the investment that was required for the holiday industry to continue to prosper and, crucially, keep up with changing visitor demands.

Captions

Dr Matthew Whitfield is an Investigator in the English Heritage Assessment Team. The result of his current research project, in addition to boosting the town’s currently poor representation on the National Heritage List for England, will be Blackpool’s Seaside Heritage, a book that traces the resort’s architectural development from its inauspicious eighteenth century beginnings to global phenomenon in the twentieth century.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.