This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

May 2022 - Central Hill, London Borough of Lambeth

Lambeth Directorate of Development Services: Rosemary Stjernstedt (lead architect), Brian Roberts, Frank de Marco and Adrian Sansom (two phases, 1967-74 and 1972-5).

When I arrived in the Lambeth office in 1969, Rosemary Stjernstedt (1912-1998) had recently left. I was advised after being given the brief for my sheltered housing scheme in Streatham to go and look at a scheme she had designed, Cheviot Gardens, a rest home on a narrow-restricted site stretching from 2 Thornlaw Road to Cheviot Road, in Norwood. She had designed this so that the two-storey circulation was a top lit atrium with gallery access either side and bridges at intervals across. I was impressed by the high standard of the detailing and finishes. All the handrails were Stainless steel. Sadly this has now been demolished. I only met her once which was at the Role Models event which the RIBA Women Architect’s group organised when I was chair, in 1986. I remember her relating how, while in the office of Robert Atkinson – where she worked on the production drawings for the Barber Institute for Fine Arts in Birmingham (1935–1939)– she found she was being paid half the salary of her male colleagues. No wonder she decided to go and work in Sweden, as of course did I. A shared experience was the encouragement of Robert Matthew, in whose Edinburgh office I did my year out. It was he who promoted her within the London County Council Architect’s Department as the first woman Group Leader, leading the team for Alton East . When she retired and moved to Wales, I was told by a mutual friend, that she bought a pair of skis!

From the collection of Kate Macintosh.

Following his appointment as Chief Architect and Planner for the London Borough of Lambeth in 1962, Ted Hollamby head-hunted Stjernstedt to accompany him in setting up the new department. Central Hill was one of the first sites that Lambeth acquired for redevelopment. As one of several hills which rise at a distance of roughly four miles from the south bank of the Thames, it enjoys spectacular views to the north. The gradient of the slope, which in places is as much as 1:3 created particular problems, especially relating to geoengineering. Arup, as the structural consultants, met the challenge by designing of 21-metre-deep piles, while Stjernstedt arranged the 374 dwellings, in a mix of six differing sizes, to step down the profile of the slope, so that intimate circumferential routes come off descending radials. The circumferential access paths lead to gates into south-facing entrance courts, protecting the front doors. Generous balconies are accessed from each level embracing the panoramic views to the north and north east. The cross section of the two-storey houses is ingenious, allowing a mix of four and five person, three and six person units with stepped profiles, and all with generous terraces. Two-person units are in four storey flats, all with balconies.

The layout was designed to protect the ancient tree-line on the ridge above and many of the mature trees within the site were retained. Originally, the six-hectare site also provided for a Doctor’s group practice, a youth club, an old persons’ day centre and shops. Architectural critic Rowan Moore has written extensively on Stjernstedt’s legacy. He stated in The Observer (31 January 2016):

It is the work of Rosemary Stjernstedt, a woman who fought a lifelong and quietly courageous battle against discrimination – from being denied access to carpentry classes at college to getting paid half as much as men for doing the same job, to exclusion from social events in some of the offices where she worked… [At Lambeth] Hollamby, for whom architecture was “a social art”, and his team learned from the failings of some earlier housing estates, such as their monolithic and impersonal nature, and introduced intimacy and variety, while still maintaining modernist virtues such as good daylighting and intelligent planning.

Colin Amery, in the Architectural Review (no. 159, 1976), following its completion, praised its unpretentious vitality: ‘straightforward, plain, well finished… [the housing] relies on the drama of the site for its architectural effects. It is remarkably clean and style-less, which is not to say that it is dull… Central Hill is no revolutionary scheme. Its virtues are quiet ones.’

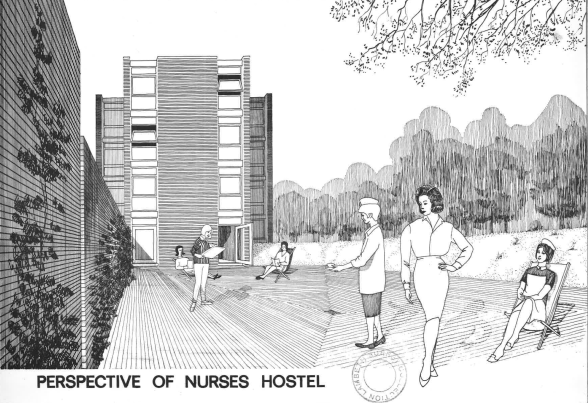

In the light of such praise from acclaimed architectural pundits, it is hard to understand Lambeth’s long-term strategy of neglect of all maintenance of this fine housing and its intent to demolish and redevelop the site. Indeed the demolition has already commenced with Truslove House, a Nurses Hostel on the site which belonged to the Norwood District Hospital; the lease to the site was given to Lambeth Council on the condition that such a hostel would be built in this location. Frank Truslove, the Chair of the Hospital Board, fund-raised incessantly for over twenty years to ensure the construction of modern accommodation for his staff. Stjernstedt, as she recalled in a 1986 talk at the RIBA, personally took on the design of Truslove House. Her consultation with the matrons and nurses led to a decision to include shared facilities such as kitchens, washing facilities and a lounge area with garden access within the scheme. With the demolition of the hostel, furthermore, came the loss of mature trees.

From the collection of Kate Macintosh.

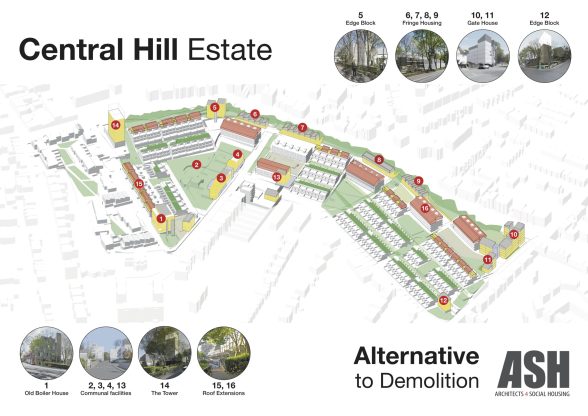

Lambeth are impervious to all the criteria and argument supporting “Retrofit First” and the push to encourage the planting and conservation of city trees. Equally they were dismissive of the capacity study carried out by Architects 4 Social Housing (ASH) and presented to them in 2017. This study demonstrated that through a combination of infill new builds (marked in yellow) on sites identified by residents, and roof extensions (marked in pink) to some of the existing blocks, ASH’s proposal shows an increase in the housing capacity of the estate by up to 242 homes. The sale or rent of a percentage of these on the private market would provide the funds to refurbish the existing homes.

Unlike Homes for Lambeth (a housing delivery company wholly owned by Lambeth Council), ASH consulted widely with the local community. In 2015 the Central Hill community held a barbeque and puppet show on the slopes of their play grounds, and in 2016 residents exhibited ASH’s designs in a marquee. This allowed large numbers of people to hear about the campaign, with over 100 residents and members of the public attending, effectively circumventing the council’s closure of the community hall. A ballot of residents conducted by the Save Central Hill Community campaign has shown that 77 per cent of residents have voted against demolition, preferring the refurbishment of the estate.

ASH’s design proposals were made with three objectives:

If Lambeth had chosen to follow this path, Central Hill could have become a pioneer project for best practice, responsible husbandry of resources as well as providing much needed housing for the people of Lambeth. Paul Watt of Birkbeck College, in his survey of “regenerated” housing estates in London, has demonstrated that on average they result in a 27% reduction in social housing, despite densification and loss of open space. Lambeth’s claim to be striving to meet housing needs is exposed as hypocritical by them keeping approximately one fifth of the houses in Central Hill unoccupied, making the district heating scheme non-viable.

Kate Macintosh is a Scottish-born architect. She was awarded the 2021 Jane Drew Prize in recognition of a lifetime of pioneering work, and for her contribution to elevating the profile of women in architecture. She was actively involved in the campaign to save the Central Hill estate.

C20 Society has worked closely with residents on the campaign to save the estate for many years. We first submitted a listing application in 2016, and included Central Hill on our Buildings at Risk list in 2017. We have also called for conservation area protection, and repeatedly emphasised both the architectural and historic interest of this very remarkable place. C20 remains strongly opposed to demolition.

With special thanks to Thaddeus Zupančič and Elain Harwood.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.