This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

August 2023 - Energy World, Milton Keynes

Imafe Credit: Wiki Commons

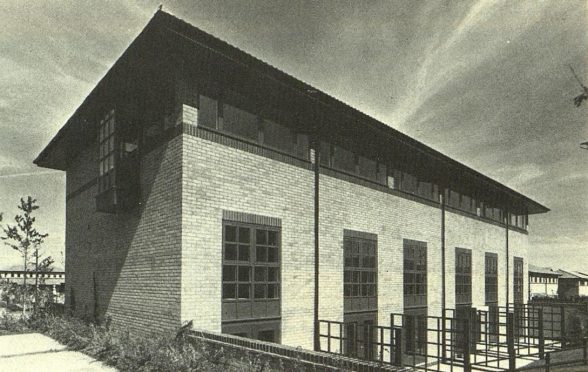

Energy World, Milton Keynes (1986)

Various architects

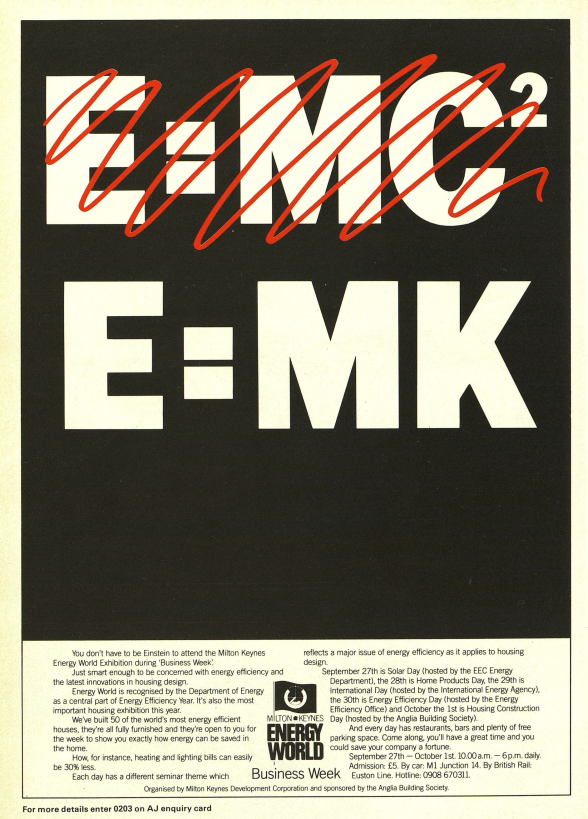

This Building of the Month is actually an entire estate. Energy World in Milton Keynes was the second of three ‘worlds’ (or housing expos) built in the new town the first being Homeworld in 1981 and the final, Future World, in 1994. Energy World was the brainchild of the Development Corporation in 1986, and was planned to be the last word in energy-saving designs. Despite the expo’s then out-of-time expression of hippy modernism, it was wrapped up in a particularly Thatcherite marketing concept, excruciatingly termed ‘monergy’.

Image: A Festival of Creative Urban Living

As well as being a collection of vastly different designs from around the world each featuring above average insulation and thermal performance, much of the energy for the estate was to be generated by the elements. The symbol of Energy World shows the path of the sun at its minimum and maximum extent for the year, and is built in brick in a small plaza, Solar Court, where it forms the platform for a vast steel sundial. Behind it stands a Palladian-style pomo community hall and corner shop, which was, when first built, a city information centre. A small turbine on Watling Street helped power a cluster of houses designed by Northampton-based David Tuckley, who was the most prolific architect in Milton Keynes, and is where I now live. These had solar conservatories that each faced south, with integral solar panels, features many of the Energy World houses had in common. Others also make use of heat pumps, heat recovery systems and trombe walls.

Image: John Grindrod

There were 47 different homes built for the exhibition, all of which are still standing – though a few, including the one designed by the town’s chief architect, Derek Walker, have been vastly altered. The list of exhibitors goes from big developers (Barratt, Wimpey, Mowlem, Laing) to Scandinavian timber-built chalets (Hedlund, Stepnell, Hosby) and utility companies (East Midlands Electricity, British Gas – whose houses are distinguished by handsome ceramic tiles announcing ‘A Gas Warm Home’). Designs vary from the most conservative Tudorbethan to the most outlandishly pomo, making it a suburb of constant surprises.

A number of significant architects worked on Energy World too. The stepped green weather-boarding on one of Trevor Denton Wayland Tunley’s Scan-Select houses is still pristine, while a second has seen a considerable amount of rebuilding work. A further set of eight modular studio houses by the practice peeps out from behind some classic MK pergolas. Passivhaus pioneer Phil Bixby’s timber framed self-build house is still largely unaltered. There’s a Colquhoun & Miller apartment block by the sundial, perhaps not their most distinguished work. At the other end of the estate a small cluster of beautiful High Tech bungalows by Fielden Clegg, with their striped brick walls, curtains of quadruple glazed south-facing glass and secret courtyards, is a real delight. The most well known of the Energy World houses was designed and built by Keith Horn. The Round House, a high-tech conical structure partially sunk into sloping earth berms, is known locally and with much affection as the Teletubbies house. Its adjustable sun-shade louvres help shade the south-facing integral conservatory. Inside the circular space even contains a swimming pool.

Image credit: John Grindrod

Legacy

The houses were designed to be at least 30% more efficient than the Building Regulations then in force. The architecture and technologies used was very varied, and included designs from Canada (the first R-2000 house in the UK), Denmark, Finland, Germany, and Sweden. Nearly 40 years later, the houses were continuing to sell for 3% above the price of other housing in the area .

Another area where Energy World continues to have an impact derives from the Milton Keynes Energy Cost Index (MKECI) , which was used to calculate the energy efficiency of the Energy World houses. Based on the results and feedback from Energy World, this was to evolve into the UK’s first national energy efficiency rating scheme for buildings, with the launch in 1990 of the National Home Energy Rating scheme (NHER) . This, in turn, gave rise to the introduction in 1995 of the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP) rating system used in the national Building Regulations and in home Energy Performance Certificates (originally introduced in 2007 as part of the Home Information Pack).

Image credit: Dave Bower

Living on the estate it is easy to imagine what it was like when it was an expo with curious visitors poking around having a look at this vision of the future. The ghosts of Energy World are everywhere, from tiles on buildings to strange landscape quirks and even the scientific street names (Laser Close anyone?). In its collision of hippy idealism, environmental design and Thatcherite marketing Energy World remains a glimpse into a last gasp of the development corporation’s ambitions for the new town – now a new city – and a reminder of what can be achieved with a sense of purpose and generous forward thinking.

John Grindrod is the author of Iconicon: A Journey Around The Landmark Buildings Of Contemporary Britain (Faber, 2022), Outskirts: Living Life On The Edge Of The Green Belt (Sceptre, 2017), which was shortlisted for the Wainwright Prize, and Concretopia: A Journey Around The Rebuilding Of Post-War Britain (Old Street, 2013). He has written for the Guardian, Financial Times, Daily Telegraph, The Big Issue and The Modernist and presented the Radio 4 documentary Living Room. He has given hundreds of talks, at bookshops, universities, literary festivals from Edinburgh to Green Man, and venues from the Museum of London, the V&A and Tate Liverpool, the National Theatre, the Southbank Centre, the House of Illustration and the Boring Conference. Twitter @grindrod

Building of the Month is edited by Andrew Murray (@aaamurray)

Image credit: British Solar Society

Image credit: Architects Journal

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.