This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Baukunstarchiv NRW

December 2020 - Former Museum for Nativity Cribs (now: Museum for Religious Culture), Telgte, Germany

Josef Paul Kleihues, with Norbert Hensel, 1992–94

This museum is a piece of urban design. In the small town of Telgte, a place of pilgrimage in Westphalia, north-west Germany, Josef Paul Kleihues (1933-2004) installed a showpiece example of how to interweave a new building within existing urban fabric. Furthermore, but certainly no less importantly, he presented in Telgte a manifestation of the theory of ‘Critical Reconstruction’ that he had developed during his time as head of the urban renewal sector (Stadtneubau) at the Internationale Bauausstellung, or International Building Exhibition, in Berlin (1987). By the time he gained the commission for the museum, Kleihues had already become an internationally renowned museum architect thanks both to his earlier projects in Germany, and especially after winning the competition for the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago in 1991. Still, he remained something of a local architect; born and raised less than 50 kilometres away from Telgte, he ran an office not only in Berlin, but also in the Westphalian town of Dülmen.

Simone Thieringer, Telgte

The building that originally served as a museum for nativity cribs and is now part of the Westphalian Museum for Religious Culture is situated at the edge of the town centre. Its north-eastern side traces the border between an area that is densely built up with deep gabled houses to the west and an open parkland alongside the banks of the river Ems to the east. This break, however, is not abrupt, but mediated by a group of buildings that are essential for Kleihues’s museum design. In close proximity, St. Clement’s church and the octagonal Chapel of St. Mary lucidly mark the realm of religion. Adjacent to the chapel, lies a barn that was transformed into a parish hall and from 1934 onwards housed a museum for pilgrimage and local history (Wallfahrts- und Heimatmuseum). This is the first of a sequence of buildings which laid the foundations for today’s museum over the following years and decades. It is surely not a coincidence that Dominikus Böhm, paterfamilias of the famous church builder’s dynasty from Cologne, in 1938 was to be the first architect entrusted with an extension of the newly installed museum.

Andreas Fernezir, 1994; Baukunstarchiv NRW

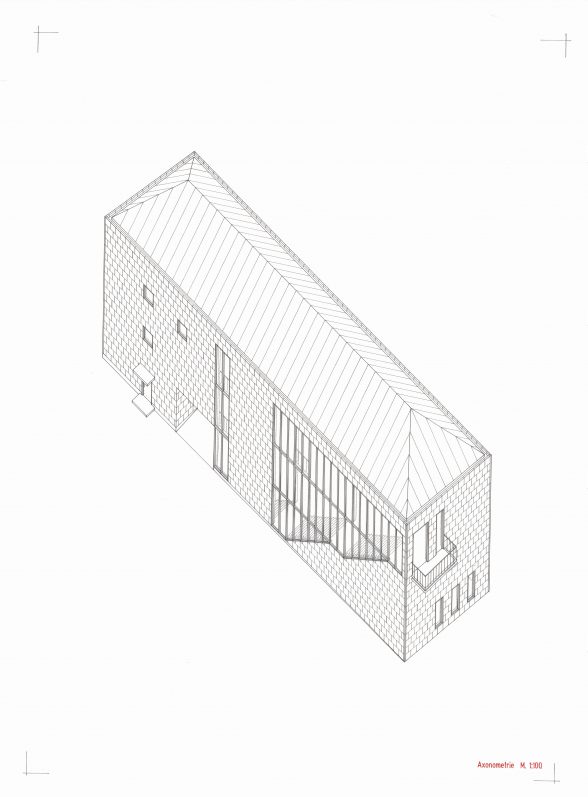

These historic buildings, dating from the 16th, 17th and 20th centuries, mark the urban setting within which Kleihues built the Museum for Nativity Cribs. His design reflects their structure and materials. By relying on the same choice of materials as the chapel across the street, for instance, the resulting building plays down its extravagance. Although the museum dominates the neighbouring buildings both in height and depth, its façade is correspondingly clad with sandstone, its roof covered with copper sheet.

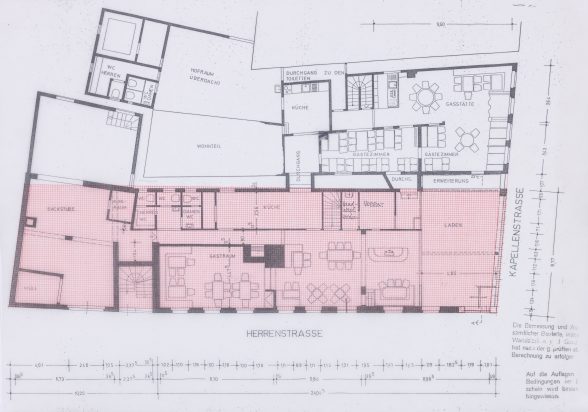

Andreas Fernezir, 1994; Kleihues + Kleihues, Berlin

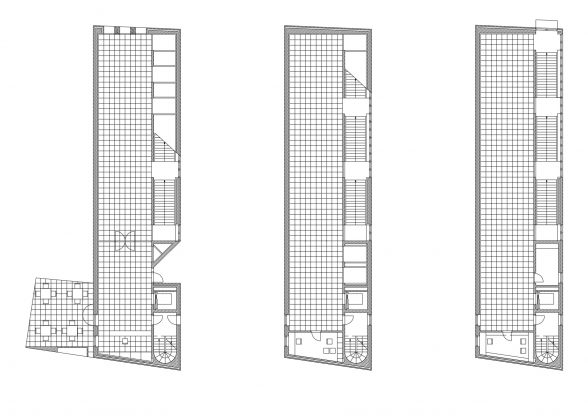

The plinth of the building intermediates between interior and exterior, since the basalt lava from which it is made reflects the dark colour of the street paving; it is included in the museum as a floor covering in the foyer and on the stairs that lead to the two upper levels. Therefore, it is not only the sacred building that serves as a treasure of motifs for the museum. It is rather the urban vicinity as a whole —it is no surprise then that the adjacent town houses also play their part in the design, as the plinth is mirrored in the corner house opposite the museum, where the museum’s second floor balcony also finds a sibling. Even vanished elements are given a voice, since the new museum replaced two existing buildings, albeit not without somewhat rigidly adopting their volumes by tracing their outer edges.

Baukunstarchiv NRW

Kleihues’s theory of ‘Critical Reconstruction’ revolves around the preservation, supplementation, and careful renewal of existing fabric, and it aims at strengthening inherent qualities without denying possibly conflicting traces of history. What is ‘critical’ then in such a kind of ‘reconstruction’? It is the fact that the architect did not only copy motifs, materials, and elements as he had found them, bringing them together in a superficial collage, but that by combining these various layers of reference, he bound together the group of buildings as a new whole. An important provider of ideas for that theory was Berlin, a city that in the 1980s was still torn by the destructions it had faced during the war and its aftermath, not to mention its division that resulted in harsh fissures in its urban fabric.

Kleihues + Kleihues, Berlin

The situation that Kleihues faced in Telgte was, in comparison, far less conflicting. Still, he fell back upon his strategy of ‘Critical Reconstruction’ in this tranquil place of pilgrimage. He even went one step further when stating that the “form of the new building and the materials used” would “correspond to the neighbouring structures in the manner of a ‘coincidentia oppositorum’ [a unity of opposites].” With this, Kleihues emphasized that the century-long history of a city brings forth a great diversity of concepts, ideas, and structures, of longings, setbacks, and memories. By placing his design into this context, he added a new conflicting, yet reconciling element to it, rather than trying to establish some kind of ‘smooth’ harmonious ensemble.

Kleihues + Kleihues, Berlin

The Museum for Nativity Cribs therefore leads to an essential thought in Kleihues’s understanding of design. It is about bringing together different, even contradictory pieces – such as the properties of a baroque chapel, an unpretentious barn or a simple town house – and converting them into a novel whole. And that is, essentially, what urban design should be all about.

Rainer Schützeichel is an architectural historian. He works as a postdoctoral researcher at ETH Zurich and teaches as a guest lecturer at the University of Applied Sciences in Munich.

The Building of the Month feature is edited by Dr. Joshua Mardell.

References

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.