This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

photo Wolfgang Thaler, 2010

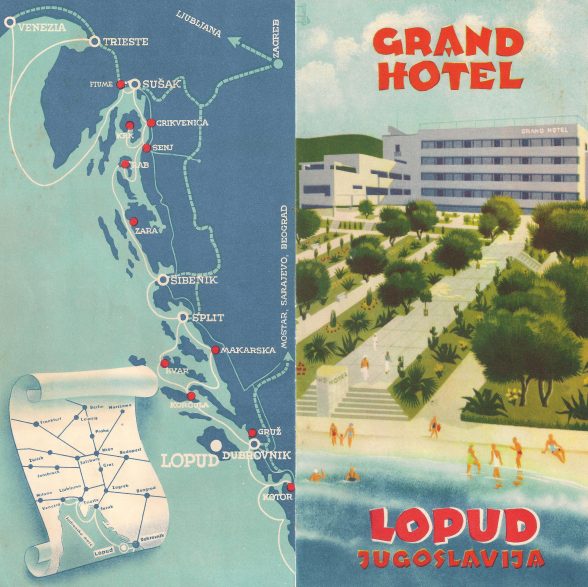

April 2021 - Grand Hotel, Dubrovnik – Lopud, Croatia

Nikola Dobrović, 1936

Lopud is the middle island in the Elaphitic archipelago, distanced a single nautical mile from the mainland and only seven miles from Dubrovnik’s northern harbour. The small town of the same name, stretched along a sandy bay protected from unfavorable winds, experienced its biggest growth during the sixteenth century. The foundations for the island’s economic development was primarily maritime trade, thus the recession in the Mediterranean after the sixteenth century led to the quick fall of the frail island economy. For three centuries, the island’s scarce population remained confined in something like a time capsule. The growth of a new service industry, tourism, incited economic restoration. The reinforced concrete Grand Hotel, which now stands abandoned in a sad dilapidated state, testifies to this short period of prosperity, just as the ruins of the Renaissance patrician palaces, the monasteries, and the Rector’s mansion testify to the island’s heyday during the Republic of Dubrovnik’s 16th century Golden Age.

The Grand Hotel was designed by Nikola Dobrović (1897-1967) in the early 1930s for the native island family. The construction took several years and represented an attraction nothing like what had been seen before, and when the hotel opened in 1936, it kicked off the development of modern tourism on Lopud. New employment opportunities were offered and a potential for development fitting the local community’s capacity was secured for several decades. The Grand Hotel is a paradigm of developmental and social sustainability derived from a local community in almost all aspects. The only aspect they needed to import was the architect himself, a man with highly technological knowledge who hailed from a distant metropolitan environment where completely different rules reigned. That is probably why he was allowed a rare extravagance, namely signing his work in his own typography with 30-cm-high letters of void space in a concrete balcony parapet above the hotel entrance:

N DOBROVIĆ ARHITEKT.

Photo: Wolfgang Thaler, 2010

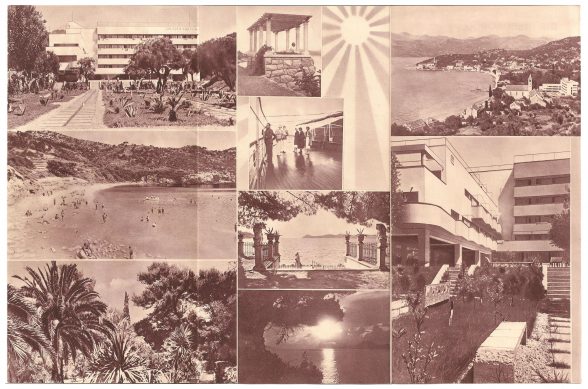

His detachment from the local scene was probably what enabled him to clearly perceive the natural assets of the island setting. Dobrović came from Prague where he completed his studies and lived on the island as a sort of professional tourist, a temporary guest from the modern world. As such, he reacted sensitively to the picturesque Mediterranean landscape and founded his entire project on close relations to the natural and cultural surroundings. The building is characterized by the minimal material consumption, the careful detailing of the minimal interior spaces, the precise horizontal and vertical distribution of the hotel units, and the emphasized “climatic” aspect of modern architecture. The use of finishing and paneling to differentiate the interior and exterior surfaces displays a clear functionalist arrangement of space. One could call what Dobrović built a summer-machine for resting, in which rooms are of minimal dimensions and the shared interior spaces modest, to say the least. Both the supporting and the supported parts of the construction are of reinforced concrete; even the original furniture in small rooms was reinforced concrete. Everything but the windows is narrow and small – but all the foyers, restaurants, and rooms face the lush Mediterranean garden and the sea. The building is imbued with nature with richly dimensioned exterior spaces: the porch under the building raised on pilotis, the roof terrace, the garden.

The building is distanced (or recessed) from the regulation line along the quay. The garden in front of it – a public park as it were, composed in an axial manner with lines of slim, tall tropical palm trees – stretches from the quay to the hotel. A panoramic terrace offers access from the quay directly to the park. Leading further to the hotel entrance, the park’s promenade is framed by a succession of open spaces with sub-tropical greenery interspersed between reinforced concrete park furniture. The dynamic spatial composition synthesizes the principles of several components of modern architecture. One sees Le Corbusier’s sense of purism in the way the spirit of the machine age is combined with the classical values of place. The minimal design and relatively enclosed appearance of the volume bespeak the sparing central-European variation of functionalism. Its smooth connection to its surroundings illustrates organic tradition, and De Stijl can be found in the experiment of creating a plastic totality. One could continue; in fact, a whole series of concurrent comparisons that would find confirmation in Dobrović’s architecture could be presented.

And so, the architect, staging the iconic sights of the times – in which a voyage equals a ship, the exotic equals tall palm trees, and hedonism equals a tennis game on a wide, flat roof – changed the life of this sleepy town forever. Agaves waving in the air atop reinforced concrete pergolas present a paradigm of total liberation in an inflection of the architectural avant-garde. Plastic unity – from the design of the landscape to the design of the built-in hotel-room furniture – makes the Grand Hotel the most consistent work of heroic modern architecture on the Croatian Adriatic coast. Not exactly in the immediate physical vicinity of the medieval ramparts of Dubrovnik but still in the heavy rhetorical shadow of this precious architectural heritage, the Grand Hotel represents a physical confirmation of the prototypical modern architect’s enlightening self-confidence, without which there would not be modern architecture, neither in Dubrovnik nor in any other place in the world.

Dr. Krunoslav Ivanišin is practicing architect from Dubrovnik, founding partner in IVANIŠIN. KABASHI. ARHITEKTI (@ivanisin.kabashi) and associate professor of architectural design at the University of Zagreb, Faculty of Architecture . He is the author of Dobrović in Dubrovnik: A Venture in Modern Architecture (Berlin: Jovis, 2015) with Wolfgang Thaler and Ljiljana Blagojević, which was the subject of a talk for the Twentieth Century Society in October 2019.

The Building of the Month feature is edited by Dr. Joshua Mardell.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.