This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

March 2013 - Graycliff Estate

Stuart McKenzie

At the start of Ayn Rand’s novel ‘The Fountainhead’, the reader is introduced to the protagonist Howard Roark just as he is being ejected from architecture school. Very quickly the reason becomes clear: Roark is completely unwilling to compromise his work to include the views of others. Indeed, at his expulsion hearing, his school dean asks him how he ever expects to win clients. Undeterred, Roark answers ‘I don’t intend to build to have clients; I intend to have clients in order to build.’

In the real world, there has been much written about the similarities between Roark and the architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Despite protestations from both Wright and Rand, a comparison is not unreasonable. Stylistically, for example, the Heller House by Roark bears much similarity to Wright’s Fallingwater: built over a cliff, made of the rock on which it stands and with strong horizontal planes following the natural strata.

However, more importantly, a strong comparison exists between the professional philosophies of both men. The quality and long lasting appeal of Wright’s work is a testament not to client obedience but to his enduring personal architectural beliefs, based on his moral ideals and his own ideas about family life, all of which are embodied in his residential projects.

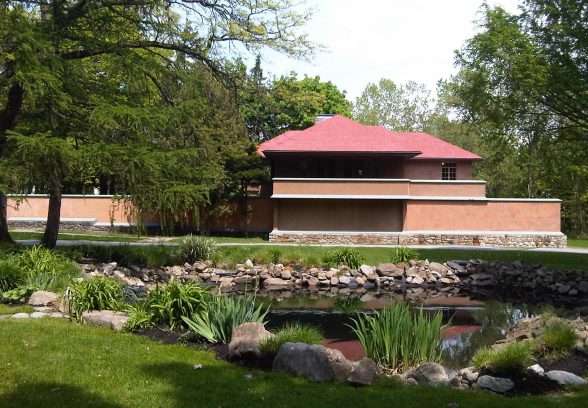

These architectural motifs and principles are very clearly encapsulated by Wright at the Graycliff estate (1926), 20km to the south of Buffalo, NY. Here, the architect was commissioned by the wife of long-time client and friend, Darwin. D Martin, to build a summer home for the family at a picturesque location by Lake Erie.

The site overlooks the lake, terminating at the shoreline in a cliff; on clear days, the upward spray of Niagara Falls is visible on the horizon. The estate consists of a main villa; a chauffeur’s house and garage, later occupied by the Martin’s daughter and family; and a heat hut located on the beach below. Wright’s conviction over the importance of the connection between a house and its place, which derives from pioneer mythology, is well documented; at Graycliff, the proximity of the lake dominates the architectural response, cleverly always visible from the house and site.

The main house is placed by the lake and its linear plan allows all of the principal rooms to face the lake. Public rooms are located on the ground floor and an additional connection between setting and house is achieved though large expanses of floor-to-ceiling glass doors. Although a ubiquitous architectural device today, pioneering technology was required to make such large openings in the heavy masonry walls. The doors create a transparency which makes the view of the lake visible right through the house. Bedrooms on the first floor open onto a large terrace also facing the water, all served by a fully glazed corridor on the opposite side.

At Graycliff, like much of his work, Wright challenged the prevailing assumption that the form of a house should be constructed as a series of enclosed (and mostly autonomous) spaces. On the ground floor, corner windows are used to destroy the conventional box form, allowing views out and nature into the building. Public spaces flow into each other and are arranged along two perpendicular axes. As a perfect antidote to the transparency, the entire ground floor is dominated by a huge hearth made from local stone. This both roots the building to its site and also provides familial security and warmth, a strong axiom of Wright’s.

At Graycliff, like much of his work, Wright challenged the prevailing assumption that the form of a house should be constructed as a series of enclosed (and mostly autonomous) spaces. On the ground floor, corner windows are used to destroy the conventional box form, allowing views out and nature into the building. Public spaces flow into each other and are arranged along two perpendicular axes. As a perfect antidote to the transparency, the entire ground floor is dominated by a huge hearth made from local stone. This both roots the building to its site and also provides familial security and warmth, a strong axiom of Wright’s.

Beyond the carefully articulated house layout, Wright also carefully controls the entire site of Graycliff, which should be read as an enlarged pinwheel plan: buildings and nature are used to form a series of spaces around which a grand promenade is weaved. Moving between the mass of the buildings and banks of trees, the site and surroundings are carefully highlighted.

The driveway bisects the site diagonally and as one moves toward the lake a vista of the water is revealed. At the last moment the house becomes visible again as the driveway curves around an artificial pond, which in itself creates the allusion of bringing the water of the lake through the house and toward the visitor.

As a rural summer villa, the house is designed to be approached by car and the front door is contained under a large porte-cochère. The chauffeur’s house is perpendicular to this entrance elevation and its continuous masonry ground floor acts cleverly as an architectural ‘signpost’, directing the driveway in a loop back to the site gates.

Wright’s ‘organic’ architectural philosophy harmonised nature with architecture; a building with its site; and the occupants with their surroundings. At Graycliff he embodied these principles with great success. The buildings are designed around their setting so specifically that it is inconceivable that they could be placed anywhere else. This is especially poignant given the prevailing architecture of the north American large house, which so often manages to only to serve as an emblem of an owner’s wealth and says nothing of its location.

Within his lifetime’s work, Graycliff marks a point of departure from the suburban villas and more truly encapsulates an architecture of nature. The total integration with site and landscape can also be read as a precursor to his later, more intense and much more famous Fallingwater , PA (1937). Graycliff itself, however, is undergoing something of a renaissance and it should soon be more widely recognised and respected.

‘Doesn’t it look like new?’ the visitor to Graycliff now thinks. And, there is good reason for this: much of it is new. The Martin family suffered badly in the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and never recovered their wealth. Darwin Martin died in 1935 and Isabelle Martin enjoyed her last summer there in 1943, before dying two years later. The house was sold in 1951 to a Catholic educational order, the Piarist Fathers, who ran the estate as a boarding school (later as a Calasanctius school for gifted children).

In 1997, the priests decided they could no longer afford the upkeep of the now much altered estate and put it up for sale. To prevent its demolition, local Wright enthusiasts formed a group to save the building, now the Graycliff Conservancy, and since then the building has been carefully looked after and repaired.

The future looks good for Graycliff. Today, guided tours of the estate are given to the public by local volunteers, a small information centre has been constructed on the site, and a plan to comprehensively re-landscape the original Wright design is underway. The place is a sophisticated example of mid-Wright work and many of his architectural values are evident to reward the visitor: Howard Roark would approve.

Stuart McKenzie is an architect and blogger based in London. He studied architecture at the Edinburgh College of Art, Glasgow School of Art and the University of Westminster. A long-term enthusiast of Frank Lloyd Wright, he visited Graycliff in 2012 as part of a larger trip to the US.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.