This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

June 2016 - Institute of Education, London

by Andy Davies

In February 1969 a momentous debate within the University of London about the redevelopment of a Georgian square in their Bloomsbury home marked the end of the free hand of authorities to plan cities in the Modernist tradition. The scars of that battle remain visible today in the juxtaposition of Woburn Square’s remaining Georgian terraces with Denys Lasdun’s Brutalist buildings.

In 1959 the University had commissioned Leslie Martin and Trevor Dannatt to produce a development plan for the Bloomsbury precinct. It won the support of both the London County Council and the Royal Fine Art Commission and led directly to Martin’s recommendation to the University that the 45-year old Lasdun be appointed to prepare the first detailed designs. Attention had been drawn to Lasdun (1914-2001) by his building for the Royal College of Physicians and his work in Bloomsbury proceeded alongside the long-awaited National Theatre (1967-76) on London’s South Bank, the crowning achievement of his career.

His brief was for a new extension to the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and a new building along Bedford Way, accommodating the Institute of Education, the Law Institute, and a near 1,000-seat auditorium. As funding was expected to come in piecemeal fashion, Lasdun devised a modular design that would allow construction to start before all the land in Woburn Square could be acquired.

The years following the commission saw a fundamental shift in public attitudes to established authority, including the authority that oversaw planning and architecture. By November 1968 a group of students and lecturers from University of London colleges started a conservation campaign to save Woburn Square. The square had been developed by the Duke of Bedford with terraces by James Sim (1829 onwards) and was punctuated by the spire of Lewis Vulliamy’s Christ Church (1831-33), which became a symbol of the campaign. The architectural historian Sir John Summerson (1904 -1992) was their figurehead. He had been a committed Modernist, simultaneously a member of the Georgian Group and the Modern Architecture Research (MARS) group, and was said to have favoured the Martin proposals originally, but had changed his mind.

A protest committee was formed and gained enough support to require an extraordinary meeting of the University Convocation on 20 February 1969, at which Summerson proposed a motion to spare at least the façades of the Georgian terraces. At the meeting convocation debated Summerson’s motion for two solid hours. The result of the division was 281 votes for and 301 votes against the motion: the wrecking ball would swing. But although the Battle of Woburn Square had been narrowly lost by the protestors, the tide had turned and university bureaucracy meant that more time would pass before Lasdun’s scheme could start on site, in September 1970.

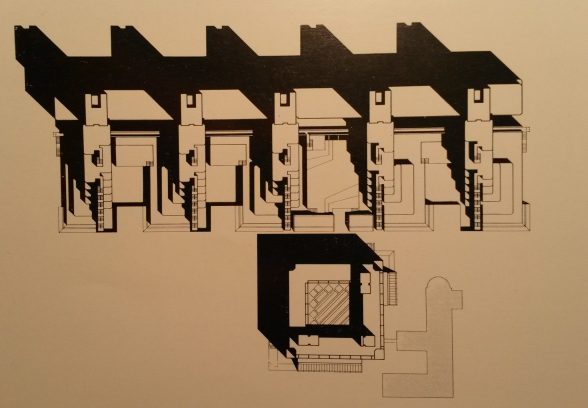

Rising from a cavernous trench dug northwards from the north-west corner of Russell Square, was a quintet of monumental concrete service towers, ranked in a dead-straight line. They were part of Lasdun’s developing urban vocabulary, an architectural system that had been used successfully in the verdant, undulating context of the University of East Anglia (1962). Virtually all of the visible concrete structure was formed in situ, in contrast with the SOAS extension, which was constructed largely from a kit of pre-cast concrete elements. Slung between the service towers are four floors of teaching and administrative space, forming a spine along the full length of Bedford Way, clad with an interlocking curtain wall of manufactured, anodised aluminium units. A subterranean service road runs the length of the spine, although a planned underground car park was never built. Martin had also envisioned a quintessentially Modernist elevated walkway connecting Russell Square with Gordon Square and beyond, but only a fragment of this survives.

Wing Block D was the first of five planned ziggurats descending from the service towers to be built. Further delays to funding gave the preservationists time to secure the listing of the three remaining Georgian terraces in the path of destruction, thereby ensuring that Wing Blocks A, B and E would never be built.

In the summer of 1974, the Church Commissioners received notice from the District Surveyor either to make extensive restorations or demolish Vulliamy’s Christ Church. By September, the site was cleared and the Institute again applied to the University Grants Committee for the finance to build Wing Block C, thus giving balance to the space enclosed by the SOAS extension, which Lasdun thought essential. The money never came, and the site remains undeveloped to this day; trees were planted to stop students playing football on it. At least the spine building was completed all the way to Gordon Square by 1978. The Institute finally added a library in 1993, although funding constraints meant that while Lasdun worked up a scheme that matched the anodised aluminium curtain walling, it would not be built to the ziggurat design that had so long been intended.

The building was not well received initially. The 800-foot monumental façade along the full length of Bedford Way, with its five sentry-like service towers rising to 115 feet, attracted most criticism. William Curtis identified it as a relative of the ‘Teaching Wall’ at the University of East Anglia, but without the softening benefit of the changes in direction there, describing it as having a “megastructural, elephantine quality…[that] does seem to lack subtlety and poetry”. By applying the same language to the grid of Bloomsbury’s streets, the building took on additional power, its straight lines implying an immovable strength. Lasdun always said that the spine was designed to “protect the precinct from the noise of traffic in Bedford Way”. However, the Institute’s Secretary Willis Dixon wrote: “We did not want long corridors, in which if you lie on the floor you can detect the curvature of the earth”.

In 2000, the year before his death, in a final, fitting irony, Lasdun’s building won its own Grade II* listing, meaning that in latter-day Woburn Square, old and new now stand forever as signifiers of a global change in microcosm.

Andy Davies

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.