This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

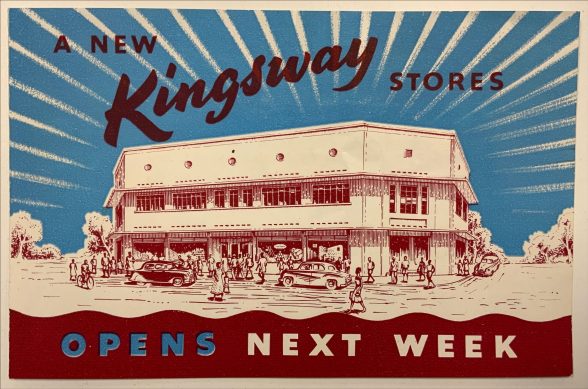

October 2022 - Kingsway Stores, Sekondi, Ghana

Picture courtesy of Unilever Archives

Kingsway Stores, Sekondi, Ghana

Unilever Architecture and Engineering Department, c1945.

Kingsway Stores was the most exclusive retail chain in colonial British West Africa. Established by a British import-export firm, Miller Brothers, the chain’s first two department stores opened in Accra and Kumasi in 1915-1920 and were explicitly modelled on Harrods and Selfridges. Named for the boulevard in London’s Holborn, where Millers was headquartered in a stodgily baroque office building, the Kingsway Stores sold imported food, clothing and home wear to a primarily British expatriate clientele. By 1929, a series of mergers and takeovers saw Miller Brothers absorbed into Unilever’s vast African subsidiary, the United Africa Company, which is currently the subject of a collaborative research project led by the University of Liverpool and Unilever Archives, and funded by the Leverhulme Trust.

Image: Prof. Iain Jackson

The Kingsway chain grew under the United Africa Co.’s ownership and by the early 1950s, Kingsway stores traded in each of the British West African capitals, Accra, Lagos, Freetown, Banjul, and in many of the larger towns and cities across the region: Kumasi, Cape Coast, Sekondi, and Tamale in Ghana, and in Jos and Kaduna in Nigeria. Like many of these stores, the Sekondi store was designed by the Unilever In-House Architects and Engineering Department, headed by James Lomax-Simpson. A graduate of the University of Liverpool School of Architecture, Lomax-Simpson designed numerous buildings for Unilever, including housing at the famous company town, Port Sunlight. The designs that his team produced for United Africa Co. offices, warehouses and retail stores across West Africa tended towards the mildly moderne, with some slight modifications for local climatic conditions through the use of canopies and verandas to provide shading from the sun and allow for the higher loads of rainwater run-off required during the rainy season. The Sekondi Kingsway store is a paradigmatic example of this work.

Picture courtesy of Unilever Archives.

The growth of the Kingsway chain in the interwar years reflected the expansion of British expatriate technicians, civil servants and businessmen during a period known as ‘the second colonial occupation.’ Increased investment in development projects, ultimately designed to maximise the flow of cocoa and precious metals from West Africa and thus boost Britain’s dollar reserves, saw not only an increase in British expatriate staff working in late colonial West Africa, but also their increasing embourgeoisement. The growth of the chain also reflected, and, indeed, facilitated, changes in the gender balance of British communities in West Africa. British women were originally discouraged from settling in the region, but by the 1940s the availability of malaria prophylaxis and yellow fever vaccines saw increasing numbers of women taking positions within colonial administrations, and wives joining their husbands on tours of duty across the region. As Laura Ann Stoler notes, the presence of European women ‘accentuated the refinements of privilege and the etiquettes of racial difference… women put new demands on the white communities to tighten their ranks, clarify their boundaries and mark out their social space.’[1] Racially segregated bungalow reservations proliferated across ‘British’ West Africa in this period. Within these reservations, ‘Europeanness’ was performed through a constant round of dinner parties, drinks parties, tennis parties, through the consumption of imported tinned and preserved food, through patterns of dress and home decoration. Kingsway stores, which emphasised that ‘orders were delivered direct to bungalows,’ supplied all the goods required for this memetic of bourgeoise English life.

[1] Laura Ann Stoler “Making Empire Respectable: The Politics of Race and Sexual Morality in Twentieth Century Colonial Cultures”, American Ethnologist, 1989.

Picture courtesy of Unilever Archives.

By the mid-1950s, as political decolonisation neared in West Africa and both civil services and expatriate companies increasingly ‘Africanised’ their staff, the Kingsway Stores faced the loss of its primary customer base. Perhaps paradoxically, the company management combatted this through a programme of expansion. Boldly modernist new stores, designed by the British commercial architectural firm TP Bennett & Partners, were opened in Accra, in the Lagos suburbs, in Ibadan and Port Harcourt in Nigeria. At the same time, didactic marketing campaigns – exhibitions, product demonstrations, fashion shows – were instrumentalised to sell a vision of modern, and, indeed, modernist, domesticity to an elite African clientele. An Ideal Homes Exhibition, sponsored by the British Design Council and held at the Lagos Kingsway Store in 1962, for example, offered advice on ‘such subjects as how to create harmony with simple furnishings and the tricks of entertaining which make a house-wife into a hostess.’[1] Kingsway at the end of empire therefore shrewdly manoeuvred itself away from selling ‘Europeanness,’ to selling ‘Modernity’ to the emerging, post-colonial, African elite, a shift in mode that sheds light on the entanglements between modernist architecture and design on the one hand, and colonial and neo-colonial profit extraction on the other.

[1] Anon, ‘Tips for the Home’, The Post, 13th March 1962

Picture courtesy of Unilever Archives.

Dr. Ewan Harrison is a lecturer in architectural humanities at the Manchester School of Architecture, and a Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Liverpool. He is currently researching British commercial architecture in late imperial Africa. He is also currently writing a monograph on R. Seifert & Partners, due to be published by MIT Press in 2023/4.

Twitter: @EwanMHarrison

The Building of the Month is edited by Dr. Joshua Mardell.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.