This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

April 2010 - Maslennikov Factory Canteen, Moscow

Yekaterina Maximova, by Clementine Cecil

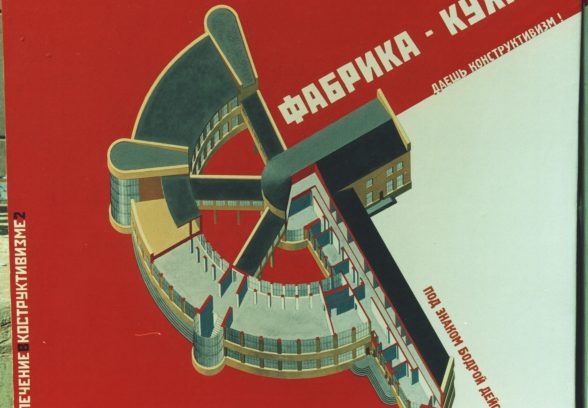

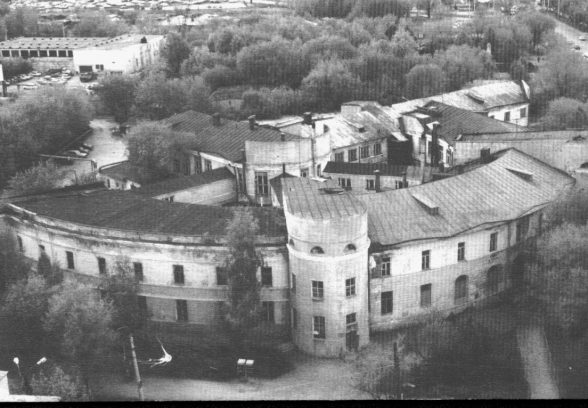

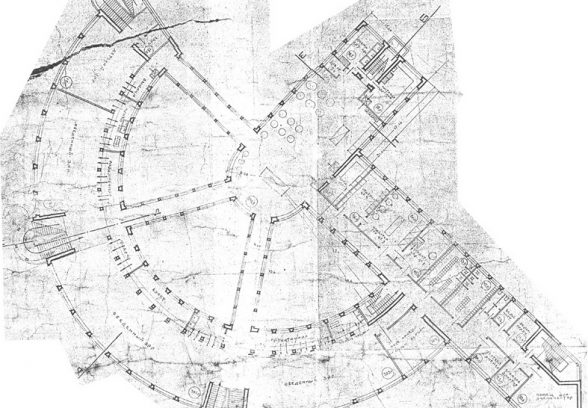

The reinforced concrete Maslennikov factory canteen (1930-1932) by architect Yekaterina Maximova has a ground plan in the form of a hammer and sickle. This was one of the earliest experiments in the use of structural concrete in the Russian provinces, an example of how metal shortages forced architects to test the boundaries of their materials. During the experimental period of the Soviet Avant-garde, concrete was an aspirational material, but builders preferred to stick to old techniques, using brick and rendering and painting it to look like concrete.

The building is a fantastic example of provincial Constructivism, little known within Russia let alone in the West.

The factory canteen, with its architecture parlante, fulfilled Lenin’s call to artists to create ‘monuments to the Russian socialist revolution.’ It also provided a necessary function: factory canteens were intended to free women from the shackles of domestic duties, allowing them to devote their energies to the building of the Soviet Union.

This was the period of the first five-year plan (1928-1932), when the Soviet Union was catching up with the rest of the world and putting all of its resources into the process of industrialisation. Until this time, Samara, over 500 miles south east of Moscow (then called Kuibyshev after a Soviet revolutionary) had been the capital of a large agrarian area on the Volga; now it was busy building factories, producing food and arms. The canteen was on the site of the Maslennikov factory which produced arms and also popular “Pobeda” (victory) watches. Food was cooked in the ‘hammer’ and transported on conveyor belts to the ‘sickle’ part of the building. Cheap, hot meals were served all day and there were also rooms where the builders of the Soviet Union could relax: a reading room and a gym.

Archival photographs of the building show that it was light and airy, with glazed stairwells – a futuristic vision of a high-tech future in which man’s brilliance could overcome nature – including the harsh cold of a Russian winter. However, in 1932 Constructivism was officially rejected as “bourgeois formalism” and like many buildings of the avant-garde, the Factory Canteen was given a classical cladding.

The building survived as a canteen and worker’s club. In the 1990s it became a shop, and ceased functioning as a canteen.

In the mid 2000s property developers SOK group bought the entire factory site and announced that they intended to raise the area to the ground and start again. This includes the factory canteen, industrial buildings, and some fine post-war modernism. Permission to demolish the building was based on the conclusions of a report by a Samara firm commissioned and sponsored by the owners of the site. They found ‘structural fatigue’ in the building, but many suspect that the conclusions were biased towards the wishes of the owners.

The campaign to save the building is being spearheaded by the Hammer and Sickle Movement. One of their spokesmen, architect Vitaly Stadnikov, edited a recent report, “Samara: Endangered City on the Volga” produced by MAPS (the Moscow Architecture Preservation Society) and SAVE Europe’s Heritage. In the report Stadnikov writes, “buildings are declared structurally unsound according to a decision from the Technical Inventory Bureau, not based on surveys, but a system of annual depreciation. This system dictates that up to 70% of the fabric of all buildings older than 1950 is dilapidated… To address this imbalance, the technical reasons for declaring a building unsound should be made public, and a clear and simple mechanism for appealing against such a decision established.”

The architecture of this period is not traditionally popular in Russia. Since Constructivism dropped out of official favour in the early 1930s, it effectively disappeared from the public eye. Today gems like the Factory Canteen are hidden, their appearance mutilated, and their functions outmoded. Property developers and the city authorities do not see the value of this building.

However, since the publication of Samara: Endangered city on the Volga, in December 2009, Samara’s deputy mayor Yekaterina Gorbunova, has said that she is in dialogue with SOK to find an alternative investor to take over the site – one that is interested in rehabilitating rather than demolishing the building. Stadnikov works in the Moscow architectural bureau Ostozhenka, and with them has developed a restoration project for the building.

Samara is home to a wealth of styles from wooden houses with finely carved window frames to neo-classical, art nouveau, constructivist, industrial and post-war buildings. It is a major Russian city, closed to the West under Communism. It was also the city to which Moscow evacuated during the Second World War.

Since the fall of Communism, there has been massive new construction and approximately one third of the old city has been destroyed. In such a climate, a project that made economic sense but preserved the building in question would be a much needed precedent for the city’s beleaguered architecture.

Clementine Cecil is co-founder of MAPS (Moscow Architecture Preservation Society www.maps-moscow.com)

Copies of Samara: Endangered City on the Volga are available from SAVE Europe’s Heritage for £15. There are not many left so get it while you can!

SAVE Europe’s Heritage, 70 Cowcross Street, London EC1M 6EJ Tel: 020 7253 3500, Fax: 020 7253 3400

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.