This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

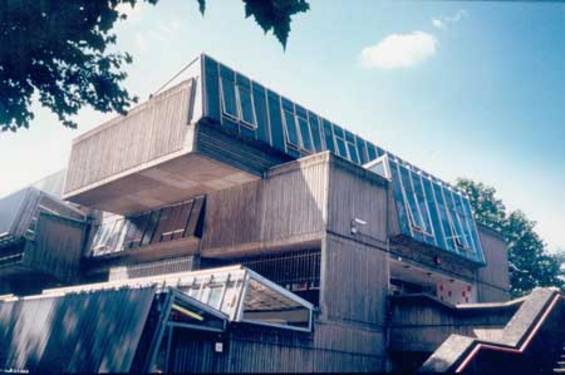

April 2007 - Pimlico School, London

Laurent Stalder Translation by Steven Lindberg

Black and white images courtesy Architectural Press archive/RIBA Pictures Collection

‘C’est magnifique, mais ce n’est pas l’école’ (it’s magnificent, but it’s not a school) – with this exclamation the reviewer for the Architects’ Journal for 1970 summarised his assessment of the Pimlico Comprehensive School in Westminster, London. ‘Battleship’ seemed more apt to him as a description of ‘this 100-odd metre long, turreted, metallic grey thing lying in its own sunken rectangle.’ It was not only the external appearance but also the overall organisation of the school that reminded the author of ‘nautical architecture’ – for example, the penetration of ‘decks’ by stairs, the clever use of limited space or the form based on volumes stacked on top of each other. Another author, in the American journal Architectural Forum, made very similar comments, characterizing the school variously as a ‘futuristic aircraft-carrier,’ a ‘very efficient educational-plant’, or a ‘green-house’. These descriptions were meant positively, as the introduction of the aforementioned article in Architects’ Journal

shows: as an ‘ancient monument of the future’ Pimlico School stood in good company in Westminster, which contained a ‘higher concentration of historic buildings than any local authority in this country’.

Strange as these metaphors may seem now, against the backdrop of 1960s optimism about technology and science they reflect the intense and highly complex debates on repositioning architecture in England during the post-war period. Even if these visions failed in part – paradoxically, precisely because of their technological inadequacy – they left a lasting impression on architectural practice not least because of their all-encompassing call for a new unity of art and technology, which was also formulated on a theoretical level. The Pimlico Comprehensive School should also be seen in this context. It was designed in 1964 in the Architects’ Department of the Greater London Council under the leadership of John Bancroft; it opened six years later, in September 1970, and won awards in 1966 and 1972 for its architectural quality. Since 1998 there have been debates over the possibility of demolishing it for reasons of inadequate climate-control technology and programmatic weaknesses.

The machine was not just a metaphor; the school was conceived as a machine in the literal sense. The concrete structure is simplified to a 6.8-metre grid of load-bearing supports with projecting suspended floors and the elimination of exterior walls and roofs in favour of large panes of glass. This should be seen as a radical response to the new technical parameters, but also a logical one. After all, the traditional protective functions of walls – blocking out light, temperature and views from outside – could be delegated to apparatuses adapted to individual needs, such as low-pressure radiator heating, automatic ventilation or sunshades.

The interest in performative forces of architecture went far beyond climatic technology, however. The system of circulation within the school was just as efficiently planned. From the central corridor on the first storey all two hundred rooms of the school could be accessed: upwards to the classrooms via a twin staircase and downwards via a twin staircase to laboratories, workshops, swimming pools and gymnasiums. The school had the ‘urban quality of a small city’, as one reviewer noted shortly after the opening. On the one hand, this description referred to the system of circulation, on the other to its full, mixed programme. The performative character of the school also went beyond efficiency of circulation. It is not by chance that another reviewer in the Architects’ Journal aptly spoke of the school as a ‘social and cultural environment’. This describes well John Bancroft’s comprehensive conceptual approach which viewed the school not just as architecture but also, far more fundamentally, as a well-tempered social ‘environment’. Against that backdrop, the school was, as remarked at the time, a futuristic aircraft carrier, education factory and greenhouse. In that sense it is a unique monument of its time, and is worthy of preservation.

Laurent Stalder is Assistant Professor for the theory of architecture (tenure track) at the ETH Zurich since February 2006. Born 1970 in Lausanne; 1996 diploma in architecture at the ETH Zurich; 1996/1997 scholarship holder at the Institute for Egyptian Construction Science and Archeology in Cairo; 2002 PhD at the Department of Architecture at the ETH Zurich; 2002-2005 assistant professor at the Department of History at the Université Laval, Canada.

Focal points of research and publication are the history, criticism and theory of architecture from the 19th to the 21st century in Europe and North America.

Visit the RIBA’s online photographs collection at www.ribapix.com

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.