This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

November 2004 - Raymond Erith’s Library at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford

Ian Nairn, the most perceptive post-war British critic of architecture writing for a broad audience, described the architect Raymond Erith (1904-1973) as “a Georgian designer – genuinely Georgian, not ‘neo'”. For Nairn, writing at the apex of the modernist hegemony in the 1960s, Erith was “one of the few genuine classical designers in Britain, his work not a pastiche of a past style but a serious attempt to make classicism work in the second half of the 20th century”.

It is appropriate that the current centenary exhibition of Erith’s work is housed at Sir John Soane’s Museum – Soane was a huge formative influence on Raymond Erith and equally an architect whose aim had been, Erith noted, “to make classical architecture progress and absorb in itself the new needs of a new age”.

Erith’s career flourished late, reaching its peak in the Sixties, and he died relatively young, his Dedham-based practice continuing, with rather different emphases, under the direction of Quinlan Terry. Two important commissions in Oxford came to Erith’s office in 1958-59: the Provost’s Lodging at Queen’s, an august ancient college in the heart of the city, and the new library for Lady Margaret Hall. “LMH” was a relative parvenue, having opened in 1879 (when it had nine students) as Oxford’s first women’s college, safely isolated in suburban North Oxford. Housed at first in a group of converted villas, it grew piecemeal over the next half century, with new buildings by Reginald Blomfield and Giles Scott. Erith’s library was completed in 1961 and followed five years later by the Wolfson West residential block, finally providing the college with a dignified point of entry. (John Betjeman compared it to a triumphal arch prefacing a great park, though it could equally be seen as a defensive bastion against marauding males.)

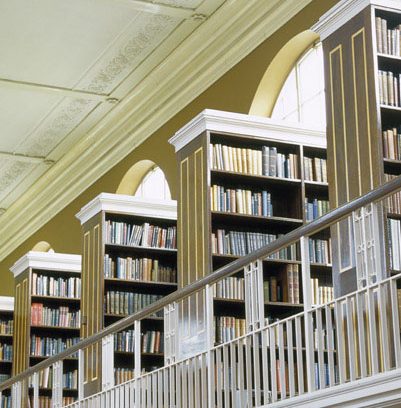

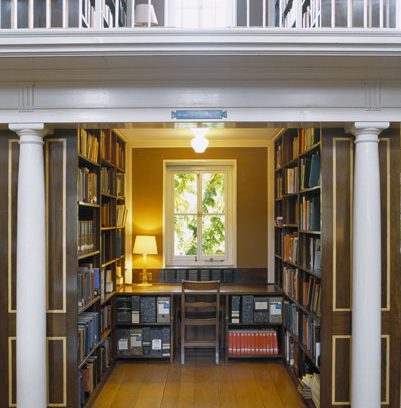

The library is, to my mind, one of Erith’s most satisfying works, but for some it seemed, when new, evidence of Oxford’s lamentable hostility to modern design, contrasting with the more progressive approach of Cambridge and the projected new universities. , a publication produced by the Oxford University Design Society in 1962, described the building as “travestied Georgian”, pillorying its construction of “nursery bricks” with “slime-green stone”. Forty years on, however, the library has worn far better than many the modernist university and college buildings of the 1960s. Erith described it as “functional” and it is, indeed, a structure with few trimmings – the adjective can be read in the light of J.M.Richards’s classic study of and of the rediscovery of Georgian and early Victorian industrial architecture. (Several unbuilt projects by Erith, including his submission for the 1948 TUC headquarters competition, look to this tradition for inspiration.) There is something of the Georgian dockyard in the LMH library, a structure constructed in the Georgian manner of brick, stone and timber – with “practically no steel”, Erith proudly boasted. (He loathed the typical neo-Georgian compromise of traditional cladding imposed on a steel frame, the basis for much of the most deadly architecture of the inter-war and immediate post-war period.) Inside, the library has something of the sober, purposeful and hand-crafted feel of a ship of the line of Nelson’s time. Everything within the building, down to the lamps, was designed by Erith and there have been no jarring alterations, though work is in hand both to expand the library’s capacity and address the issue of disabled access – both can be achieved without damaging its quality, but this is, in the end, a working building. It is only regrettable that so much classical architecture of more recent vintage eschews the straightforwardness and practicality of Erith’s work in favour of the sort of extraneous styling that he rightly despised.

The exhibition Raymond Erith, Progressive Classicist, 1904-1973, is at Sir John Soane’s Museum until 31 December.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.