This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

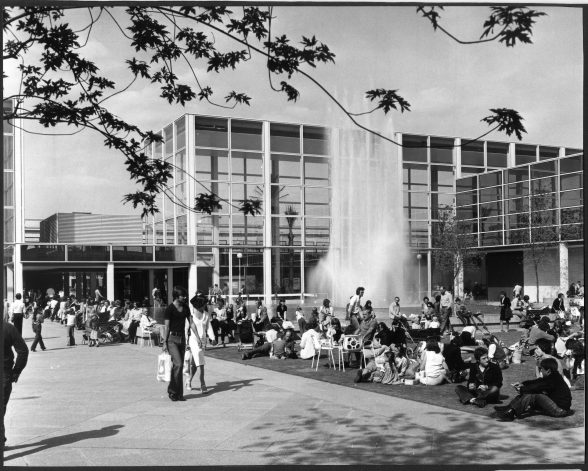

Photo: Courtesy of Living Archive

June 2021 - Shopping Building, Milton Keynes

Milton Keynes Development Corporation, 1975-9

On 25 September 1979, the recently elected prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, declared the Shopping Building in Milton Keynes open for business. The largest indoor shopping centre in the UK represented exactly the kind of consumer-driven urban environment that thrived under Thatcherism. The installation of such a large-scale commercial space as the civic core of the town, before work on the Milton Keynes Hospital had started, epitomised the rise of individualism and consumerism. The Shopping Building, as it was known at the time, was likened to a place of worship for a consumer society; it was called a ‘potent symbol’ of the times in the Architects’ Journal (1980).

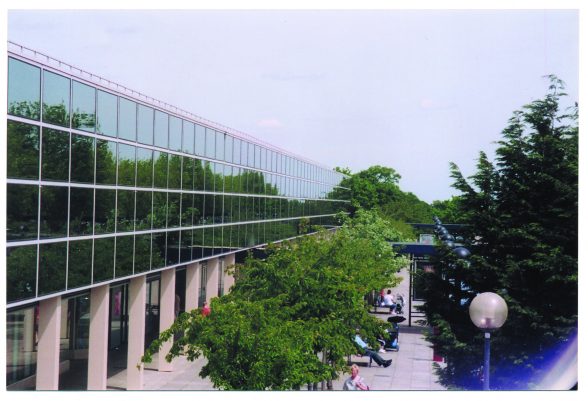

Photo: Courtesy of Living Archive

That was never the intention of the young and ambitious architects who designed one of the twentieth century’s most (in)famous shopping centres. Following the approval of the Master Plan for Milton Keynes in 1970, two squares of the New Town’s loose grid were designated Central Milton Keynes. Under the leadership of Derek Walker, Chief Architect for the Development Corporation from 1970-1976, the CMK design team was formed, all of whom were under the age of 40 and schooled in the principles of modernist architecture – taking direction from the likes of Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and the Smithsons. The construction of a town centre provided them the opportunity to set the precedent for innovation and high-quality design across the rest of the, then largely undeveloped, New Town.

As with earlier New Towns and post-war town centre redevelopments, the Shopping Building in Milton Keynes marked a departure from the traditional high street model. But the architects’ ambitions were also to subvert the increasingly homogenous shopping centre found in these earlier developments. The shopping centre in the early New Town of Cumbernauld, was one of the first Victor Gruen-style malls to open in the United Kingdom in 1967 – and it was one that the design team visited and were keen to avoid. The Gruen-style shopping mall, a product of a mid-twentieth century shift in public, private and consumer lifestyles, embodied ease – and easy entertainment – at the expense of a traditionally diverse urban realm. As Walker explained, in conversation with CMK architect Chris Woodward and Terence Conran in Architectural Design (1974), “What we are trying to do is make this pleasurable, and to halt the American syndrome of the twin dumbells of two department stores growing to such an extent that speciality shopping is squeezed out, social ingredients are avoided and circulation becomes a nightmare.” Instead, the CMK design team hoped to coalesce the civic infrastructure of the nineteenth-century arcade and the natural environment into a “cool series of enjoyable streets varied in their landscaping, natural but with the unoppressive canopy of shelter.”

Photo: Courtesy of Living Archive

Photo: Ellen Brown, 2018

One arcade that inspired the design team was the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan (1865-77). Like the Galleria, the Shopping Building would provide a space that could simultaneously assert its status as a symbol of modernity and evoke a sense of civic pride amongst its community. As CMK architect, Chris Woodward, would later recall, Passagen (1969) by German architectural historian Johann Friedrich Geist, dedicated several pages to the Galleria and was read by the design team. Natural light flanks the interiors of both the Galleria and the Shopping Building, highlighting the structural qualities of the respective curved cast iron and rectilinear steel and glass. Walker, Woodward and fellow CMK architect, Stuart Mosscrop, were keen to point out that the Shopping Building was not a shopping centre. With two parallel glass-lined steel arcades, the Shopping Building was to be a covered high street and civic centre.

Like the Galleria, civic life was built into the framework of the Shopping Building, evoking the communal values of public life. Italian travertine stone was used throughout the building for flooring, wall veneers and to house planters that run down the centre of both arcades. Likewise, the building was designed to inculcate civic pride and cater for the public social interactions, whilst also fulfilling its obvious commercial purposes. Two squares, one covered, one open-air, would be used for eating, drinking, exhibitions, sports events and even busking. A series of renderings of the Shopping Building by the architectural illustrator, Helmut Jacoby, depict families casually strolling under tall trees through the light-filled rectilinear arcades.

Photo: Courtesy Living Archive

When the Shopping Building first opened, there were no doors. This contributed to the conceptualisation of the space as ‘permeable’. The two interior arcades run parallel with the two boulevards that run the length of Central Milton Keynes, and are intersected by a series of Walks that connect to public walkways. The lack of doors provided ‘convenient and unobstructed’ access across the town centre at all times. Nonetheless, doors were added soon after, following complaints that strong winds were blowing cold air and foliage into the arcades. In the late 1980s, the Shopping Building was sold to a private owner; the doors were locked at night, and soon after the space was first referred to as a shopping centre. From then on, as it was noted in The Buildings of England: Buckinghamshire in 1994, it became “just like any other shopping centre.”

Though the Shopping Building was unlike other shopping centres of the time, its architectural vision was not universally welcomed. In the Architects’ Journal (1980), the architect Peter Smith disparagingly concluded of the Shopping Building that “I don’t even think that one can blame (or credit) Mies or the Modern Movement with this phenomenon”. These Miesian qualities have, however, become a contributing factor in awarding the Shopping Building a Grade II listing in 2010 (something the Twentieth Century Society played no small part in). Over the past 30 or so years, the original Shopping Building has been subject to modifications, including the addition of a Marks & Spencer flagship in 1993 over a public square at the most westerly exit of the building. The extension was designed in keeping with glass and steel rectilinear arcades, but its impenetrable mirrored glass achieves the inward-looking effect of a concrete-walled Gruen-style mall that the CMK design team were resistant to.

Photo: Courtesy of Living Archive

In the months leading up to the opening of the Shopping Building in 1979, Derek Walker voiced his concerns in an article for RIBA about the reception and future of Central Milton Keynes. He noted that, as a result of a changed political mood, a depressed economic climate, and a sudden reluctance to invest in civic and cultural facilities, some of the ‘original qualities’ of the Shopping Building had been compromised. Central Milton Keynes was at a crossroads; the CMK design team had created a ‘beautifully finished’ structure that would, it was hoped, set the precedent for future architectural achievements, but the real test was how the Shopping Building would be used. Though some of the original features of the Shopping Building have been lost or compromised over the years, and it exists more as a commercial space, the aspirations of the design team for a steel and glass arcade in the middle of a barren Buckinghamshire landscape, marrying aesthetic, civic and commercial intentions, can still be traced.

Ellen Brown is a writer interested in space, photography and consumption in the context of broader political and cultural ideas. She is planning to undertake a funded PhD at the University of Warwick, looking at post-war shopping centres in a post-Covid climate.

The Building of the Month feature is edited by Dr. Joshua Mardell.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.