This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

July 2023 - Sloan House, Glenview Illinois

Image courtesy of Anthony Denzer

Sloan House, Glenview Illinois, United States (1939-40)

George Fred Keck (Keck and Keck Architects)

Long before the Twentieth Century, builders sought to understand and use solar heat, as John Perlin shows in Let It Shine: The 6,000-Year Story of Solar Energy. Ancient Romans built their monumental baths with enormous south-facing windows. Those inside would ‘broil’ in the afternoon, according to Seneca. The understanding of solar geometry even appears in Shakespeare, as Casca vividly traces a path across the sky with his sword, describing the seasons, in The Life and Death of Julius Caesar.

But the story of the modern solar house begins in 1940, when architect George Fred Keck built the Sloan house in the Chicago suburb of Glenview. Though not well-known, it made a splash at the time, and in retrospect it clearly represents a new form of architecture based on scientific knowledge and a prescient concern for energy efficiency. In The Solar House: Pioneering Sustainable Design, I argue the Sloan house “changed the course of 20th century architecture,” and I conclude Keck was “the first solar architect.”

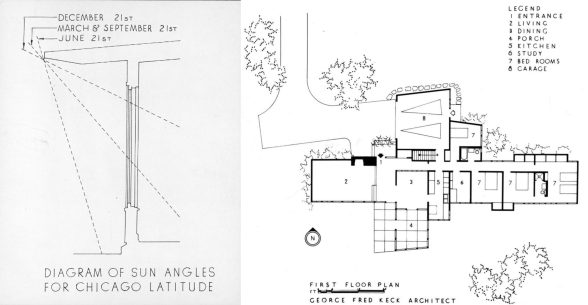

In the Sloan house, Keck employed a menu of strategies that would come to define the (passive) solar house, and all of these strategies remain sensible and energy-saving today if designed with care. He created a shallow linear plan, over 100 feet long, with all rooms facing south. A tall ribbon of glass defined the south elevation, while only a few small windows looked north. The south wall also featured overhanging eaves, designed to admit winter sun but shade the glass in the summer. Because of his experience in building the all-glass “House of Tomorrow” (1933), which suffered severe overheating, Keck understood the importance of shading. He was probably the first American architect to draw shading diagrams based on solar geometry, establishing a graphic convention followed by passive solar architects for generations. Keck also gave the Sloan house a representational flourish: two ‘uplifted’ roofs at the center, which seemed to reach for the sun.

Never before had an architect attempted to calculate how much solar heat gain would be realized. Keck’s younger brother William made handwritten computations to compare daily losses and gains for the Sloan house. The designers wanted to predict the client’s savings for the winter, and later check the prediction against the actual energy use. They estimated that Sloan would save about 20% on his heating bills, but also worried about overheating at certain times.

Image courtesy of Anthony Denzer

Further, the Sloan house included four times as much roof insulation as standard practice. This is revealed in the typewritten specification documents where Keck crossed out ‘one’ inch of rock wool and wrote ‘4’ in red pencil. Clearly, Keck comprehended the importance of a robust envelope, and he prioritized energy efficiency at a time when most Western architects designed with enthusiasm for mechanical heating and cooling.

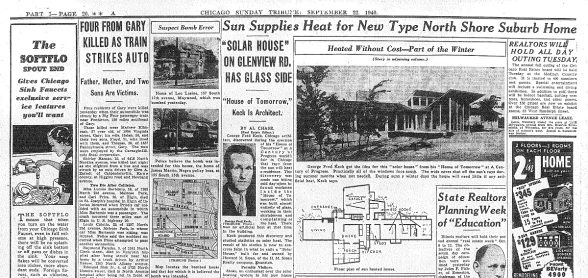

Howard Sloan, the client, was a real-estate developer and master of public relations. He cleverly persuaded the Chicago Tribune to promote the project with the headline “SOLAR HOUSE”—the first instance of that label in the history of architecture. Sloan opened the house to the public with a ten-cent admission, and thousands visited, finding it an “agreeable and a pleasant place to be,” according to Keck. After the first winter, Sloan examined his heating bills and found he had, indeed, saved 20% compared to a typical house. Sloan then engaged Keck to design the neighborhood, called Solar Park, and he found the solar houses “sold faster than we could build them.”

Image courtesy of Anthony Denzer

Quickly, by the mid-1940s, the solar house became a familiar concept, promoted by publications such as Newsweek, Reader’s Digest, and the New York Times. Numerous architects adopted Keck’s basic strategies—a linear plan, south-facing insulated glass, and proper shading for summer. In the second Sloan house (1942), Keck had added to this menu by introducing “Thermopane” windows, ventilating louvers, and concrete floors with radiant heating.

During the energy crises of the 1970s, passive solar and energy efficient homes became a high priority, especially in cold climates. The Keck brothers were recognized as pioneers, and the Keck-style solar house was known to be effective, low-tech, and replicable. Today, the Sloan house remains in its original form and has been well-maintained by private owners.

Anthony Denzer is the Professor and Department Head of Civil and Architectural Engineering and Construction Management at the University of Wyoming and is the author of ‘The Solar House: Pioneering Sustainable Design’ (Rizzoli, 2013).

Twitter @tdenzer33

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.