This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

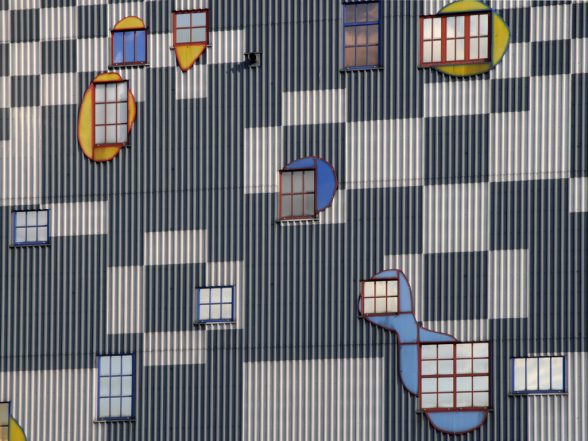

September 2023 - Spittelau Incinerator, Vienna

Image: Wien Energy

Spittelau Incinerator, Vienna (1992)

Friedensreich Hundertwasser

Waste incineration, also known more palatably as ‘energy recovery’ or ‘district cooling’, has historically been critical to many Northern European economies which have dispensed with landfills over time. In Austria, industrial scale incineration started in the early 1960s, with the first incinerator built in 1963 in Flotzersteig, a neighbourhood in the far west of Vienna. The purpose of this incinerator was to provide energy and heating to the locale. The subsequent Spittelau waste incineration plant in Vienna, inaugurated in 1971, is a remarkable exception in its design if not its services. Today catered to by 250 vehicles daily, Spittelau incinerates a third of the waste in its borough (approximately 250,000 tonnes per year), and it provides energy for roughly 60,000 homes alongside cooling to nearby hospitals and universities.

Image: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra

Austria consistently scores well in waste incineration international rankings, and Spittelau undergoes major renovation on a regular basis to improve its efficiency. But incineration in principle is not without its critics. The practice produces toxic fumes and necessarily cannot be carbon neutral with even the most advanced filters. A secondary consideration is the high potential for mercury and lead contamination in the local water supply. The redesign project of Spittelau in the 1980s would be the Austrian artist-architect Freidensreich Hundertwasser’s second most significant intervention in Vienna after his seminal Hundertwasserhaus (1985). As a project it represents his complex relationship with energy generation and use in the latter part of his career. Hundertwasser speculated in 1983 that the energy crisis of the previous decade was predicated on ‘an extravagant squandering of energy’. The provocative statement was typical of Hundertwasser, who wrote polemically on matters ranging from art to architecture to the environment across his career.

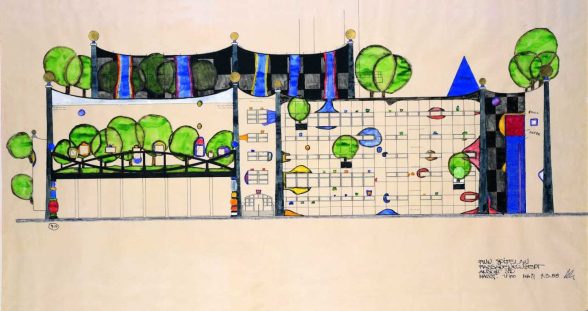

Image: Hundertwasser Archive

Hundertwasser began his career as an artist in the mid-1940s, painting until the mid-1950s. What was generally considered his ‘outsider art’ approach was consolidated as he pivoted from the field of art into architecture in the late 1950s. Hundertwasser saw architectural education as overwrought and indicative of a gatekeeping profession that prevented most people from engaging in design and construction, and he spoke publicly on this point repeatedly. His ‘Mouldiness Manifesto: Against Rationalism in Architecture’ lecture, given in Munich in 1958, refers disparagingly to the gulf between the ‘free’ contemporary status of painting and sculpture, and ‘planned’ architecture that necessarily precluded the ‘freedom to construct’. While Hundertwasser initially proposed that anyone should build their own structures without formal training, this stance had softened by 1968, when he was advocating rather for tenants’ extensive tampering of existing buildings to suit their needs and desires.

Image: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra

In the 1970s Hundertwasser engaged in various environmental projects at a local level, including the Mehr Grün für Wien (‘More Green for Vienna’) initiative to increase green space in the city, alongside several national anti-nuclear campaigns. His ecological advocacy dovetailed with his move into practising architecture, with a series of remodelling projects in the early 1980s at the Rosenthal Factory in the German town of Selb, and the Mierka Grain Silo in Krems, Austria. The remodelling projects chimed with a conviction that existing buildings should be retained, rather than demolished and built anew. Rejecting the term ‘architect’ for its elite connotations, Hundertwasser began using the title ‘architecture doctor’. The term points towards the rehabilitation of buildings’ appearances and uses, but pointedly also of their recovered status as sustainable entities set apart from the formal architectural profession.

Image: Besser Stadtleben

Located in the Altangrund neighbourhoood of north Vienna (next to the Donaukanal arm of the Danube), Spittelau was built in a modernist style in the late 1960s. Inaugurated in 1971, its initial function was to provide energy for the air conditioning of the Vienna General Hospital. It was extensively damaged by fire in 1987. After lengthy debate about relocation, the city authorities decided to rebuild the existing structure, due to the generally intact heating and cooling systems, and the fact that Spittelau’s location close to the heart of Vienna could not be improved. The same year, Helmut Zilk, then mayor of Vienna, asked Hundertwasser if he would be interested in redesigning Spittelau as a ‘work of art’. As a heavily damaged building that was critically also functionalist in design, Spittelau was the ideal patient for Hundertwasser, but for the obstacle that waste incineration was not a green activity.

Image: Hundertwasser Archive

Against advice from some of his environmentalist colleagues (including campaigner and biologist Bernd Lötsch), Hundertwasser was ultimately convinced by Zilk’s arguments that the incinerator would provide the gold standard for sustainability, including restrictions on the volume of waste burnt and the highest possible reduction in toxic vapour emission, researched and substantiated by a team of appointed technicians. The design was completed in 1987 and the plans executed between 1988 and 1992. The building is most notable for its golden globe and ‘crown’ on the plant tower and Hundertwasser’s trademark disregard for his architectural bugbear, the straight line. It is colourfully painted across the main facades with golden ball finials accentuating the corners of the building and a single storey extension with symbolic planted trees. Hundertwasser said that in redesigning the plant he intended to create a ‘true memorial for a more beautiful world without waste’. It is difficult to know how to assess this statement considering the problematic (if perhaps unavoidable) practice of waste incineration at all, and Hundertwasser’s tendency towards hyperbole in his written work.

Image: Plastics Mag

In 2021 the energy provider that manages Spittelau, Wien Energie, instated its logo on the roof of the building to mark the plant’s fiftieth anniversary. Its former logo, ‘Fernwärme Wien’ (‘Vienna District Heating’) was removed, and the individual letters handed over to the Kunsthaus Wien as a piece of ‘Spittelau history’. Whether or not Hundertwasser’s intervention was ecologically or aesthetically successful, it has drawn attention to the existence of waste incineration to an entire city and beyond. Hundertwasser’s democratic and environmentalist inclinations, generally directed against the formal architectural profession and exemplified at Spittelau, represent part of the diverse anti-modernist backlash that emerged in the middle of the post-war period.

Joe Mathieson is Architectural Advisor at the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, and a C20 tour leader, casework committee member and volunteer.

Building of the Month is edited by Andrew Murray (@aaamurray)

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.