This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

© Matthew Lloyd Roberts

April 2020 - St Mark’s, Biggin Hill

Richard Gilbert Scott, 1959

Biggin Hill sits atop an outcrop of the North Downs, now finding itself in the southernmost fringes of the London borough of Bromley, tucked just inside the M25. The parish church of St Mark’s originated in the early twentieth century, as a temporary corrugated iron mission church, serving the tiny population of the hamlet of Biggin Hill, which at that point was decidedly part of Kent rather than London. However, the Second World War redefined this small corner of the garden of England, as the aerodrome became one of the busiest RAF bases in the Battle of Britain. The memory of the war is inescapable for residents of this part of the world: children play at the Spitfire Youth Centre, their grandparents meet for tea at the Spitfire Cafe, and the drone of Spitfire engines are constantly audible as they joy ride wealthy nostalgics through the crisp Kentish skies for as little as £2,750 a go.

In the bricks of the church of St Mark’s however, there is a palpable reminder of some of the realities of midcentury life, with its vast socio-economic upheavals, that doesn’t always get included in the popular imagination of the Battle of Britain and the historical aftermath of the war. In 1951, Vivian Symons, a recently discharged Cornish serviceman and chaplain, was made the Perpetual Curate of the mission church of St Mark’s. The tin tabernacle of 1904 was ailing badly and was completely unfit to accommodate the explosion of Biggin Hill’s population, which had passed 4,000 people. This population growth was fueled by the air conflict of the Second World War, as state investment in Biggin Hill brought huge numbers of people to the area. This process was accelerated by the bomb damage inflicted on inner London, which pushed Londoners out of the dense Victorian, Edwardian and interwar urban centres and out to commuter towns which were growing at tremendous pace in the decades after the peace.

© John Salmon

The church of St Mark’s embodies this process. With building licences impossible to attain, and funds in short supply, the present-day church is predominantly built from the fabric of the Victorian Gothic church of All Saints, Surrey Square, Peckham, designed by R. Parris and S. Field in 1864. All Saints suffered damage during the Blitz that rendered it unusable as a parish church, and a lack of funds for its restoration due to a much-diminished congregation, caused by the depopulation of inner London, enabled the charismatic and deeply driven Vivian Symons to orchestrate its deconstruction, and the transportation of 125,000 bricks, 200 tonnes of stonework and the entire timber roof of the old church to Biggin Hill. The Pathe news footage of the deconstruction is unmissable for the boundless energy of the Perpetual Curate and the haphazard safety standards of the work.

Among the volunteers perilously deconstructing the church in Peckham were a group of schoolboys from Harrow School, and through them, Giles Gilbert Scott was approached to give architectural direction to the new construction of St Mark’s. Giles declined the commission, but put forward his son Richard, who would have recently turned thirty. St Mark’s remains as the earliest large-scale architectural project of Richard Gilbert Scott, and a profoundly interesting fusion of the literal materiality of Victorian church architecture with Gothic elements that are extruded through the abstracting prism of Richard’s designs. This abstraction of Gothic decoration and elements clearly owes a debt to the work of his father, but also takes the concept to much starker and inventive territory. This technique, and the creeping influence of modernist massing, would follow his work throughout his career, particularly in his extensive work for Guildhall Yard in the City of London.

© Matthew Lloyd Roberts

St Mark’s offers an almost inverted image of Hilda Mason and Raymond Erith’s St Andrew’s at Felixstowe (1929-31). St Andrew’s maintains the massing of a Suffolk wool church, with abstracted details, but made from the innovative building material of concrete. St Mark’s uses the literal materials of Victorian church architecture, with abstracted details, to produce a stark, triangular mass and tapering freestanding campanile that evokes the aircraft hanger and air traffic control tower more than the parish church.

© Matthew Lloyd Roberts

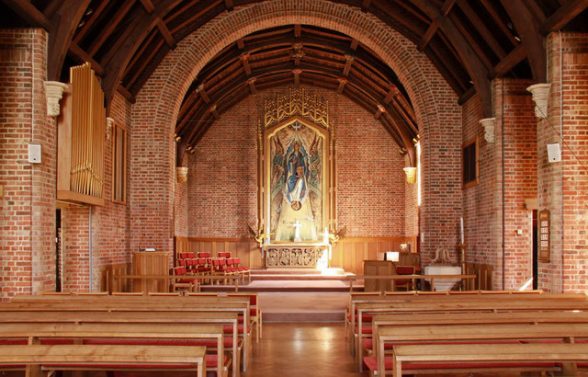

From this declarative exterior, the yellow stock brick gives way to the softer red brick of the interior, with curved corners detailing the piers of the aisles and a vast sweeping arch denoting the separation of chancel and nave. The windows are engraved with scenes from the woodcuts of the Biblia Pauperum (Paupers’ Bible), work carried out by the inimitable Symons with a dentist’s drill over his many years as parish priest. Above the altar stands a reredos by Roland Pym, which reminds us of what this church represents, the dying tree of a bomb damaged All Saints reborn in the dominant mass of the west front of St Mark’s. A monument not only to a singularly driven parish priest, but also to the economic and social reverberations of the Second World War, and the reforging of the dynamics of greater London that it precipitated.

© Matthew Lloyd Roberts

Matthew Lloyd Roberts produces the architectural history podcast ‘About Buildings and Cities’ and works at the Architectural Association. The Building of the Month feature is edited by Dr. Joshua Mardell.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.