This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

June 2023 - Street Farmhouse, Eltham

Courtesy of Dr Stephen Hunt

Street Farmhouse, Eltham (1971-72)

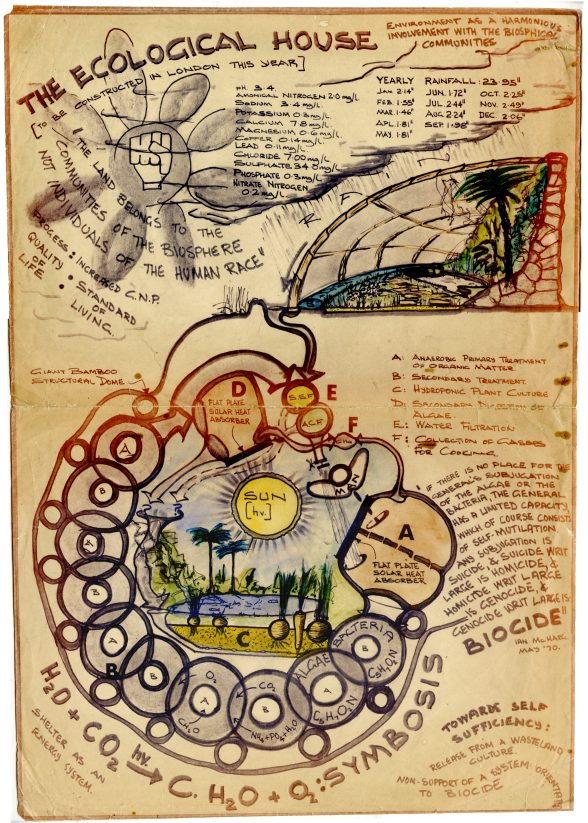

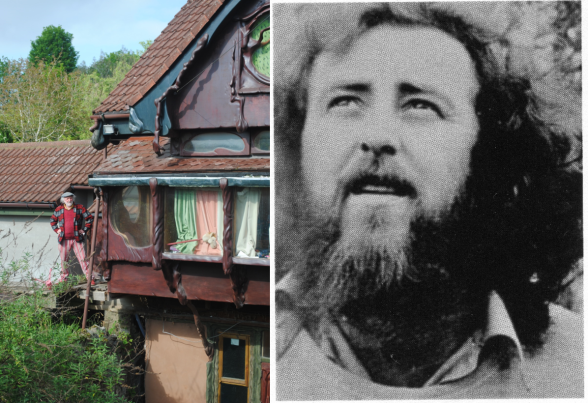

Graham Caine

A key claim in my book The Revolutionary Urbanism of Street Farm was that Graham Caine had designed the world’s first ecological house, in 1971. I fully acknowledged that countless indigenous and vernacular dwellings have been equally, often more, sustainable. Yet Graham had intentionally set out to construct a house conceptualised as ecological. He began drawing up plans for the project as a student at the Architectural Association in early 1971 and told me that “To the best of my knowledge, nobody had used that term before.”

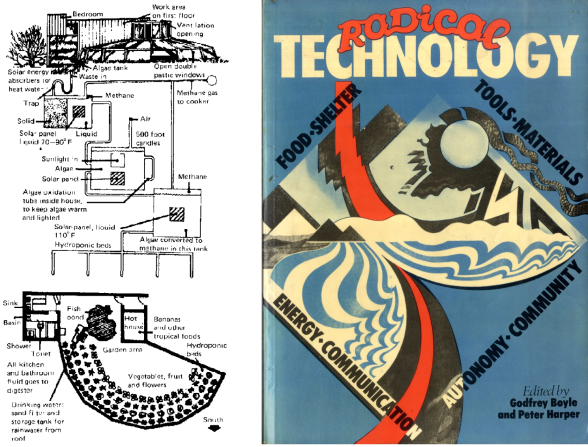

Graham Caine Archive

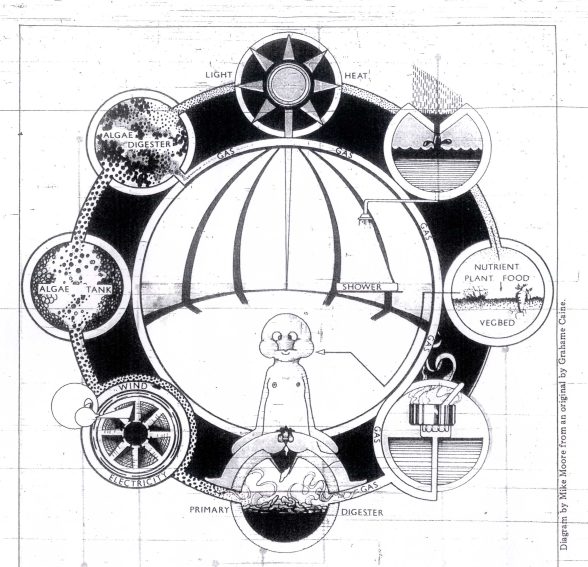

What is incontrovertible was that the completed dwelling was a pioneering exemplar of political ecology applied to sustainable architecture. Graham named his construction Street Farmhouse to align with Street Farm, an anarchist collective he had initiated with fellow Architectural Association students Bruce Haggart and Peter Crump. The ecological house was an early attempt to put into practice ideas about community autonomy, alternative technology, and renewable energy. Increasingly, these were to find expression in publications such as the journal Undercurrents and the countercultural compendium Radical Technology (1976), as well as the national Comtek (community technology) festivals held in Bath during the mid-1970s. Graham was brimming with ideas for affordable low-impact housing that he aimed to synthesise in a living experiment. He was eager to monitor the performance, self-critically learning from any failures, with the hope that the parts that worked could be developed and scaled out.

Courtesy of Dr Stephen Hunt

Street Farmhouse was self-built on the Thames Polytechnic’s playing fields in Kidbrooks Lane, Eltham. Construction began in 1972 after the local planning department at Woolwich had given the go-ahead under a two-year provisional permit. At first sight, the ecological house appeared shanty-like, little resembling many of the expensive bespoke eco-homes to come. It was made up of two units; a wooden cabin-like structure, comprising the main living quarters, supplemented by a polyhedral greenhouse. Nevertheless, at the time there were several principles embedded within Street Farmhouse that led Oz magazine to describe it as “a revolutionary structure.” The ecological house was revolutionary in three senses: it was innovative, politically radical, and its working mechanisms were intended to revolve around regenerative cycles.

Courtesy of Dr Stephen Hunt

Street Farmhouse was an exercise in participatory architecture, with Graham, his partner Fran Stowell, and friends from the wider Street Farm circle assembling the dwelling between August and December. Graham felt that the home he shared with Fran, and their new-born daughter Rosie, should model the value of creative collaboration rather than consumerism. This idea was carried further in the commitment to low-capital inputs so that others could afford to emulate its design features. Since, typically, the generation of capital can have a negative ecological impact, it was important that the consumption of resources and energy was not simply displaced elsewhere. As far as possible, the materials were recycled and borrowed. The construction costs in 1972 were approximately £700 (equivalent to £7,700 in 2023). Above all, Graham sought a measure of self-reliance and autonomy. Nonetheless, he was keen to stress that he thought of autonomous living as a strategy to liberate housing and communities from dependency upon the state and private corporations, not as a form of selfish individualism. He stressed that he was neither philosophically nor technologically trying to devise a closed system.

Courtesy of Dr Stephen Hunt

In keeping with these principles, the ecological house was intended as a prototype to trial and demonstrate how interrelated elements could complement each other in an integrated regenerative system. Many technical features were incorporated to meet this end. These included a semi-hydroponic growing space, an anaerobic digester to generate methane from human waste, solar collectors, and measures to harvest rainwater and capture ambient light. Heat generated in the greenhouse was transferred to the generously insulated cabin. Graham maintained, therefore, that the paraffin heater kept as a fall back was little used. Finally, a Savonius wind turbine was installed for microgeneration to further efforts to go fully off-grid. Graham rarely left the area, meticulously monitoring the functioning of the ecological house. Nevertheless, he insisted upon his amateur status and that it was a home, not a laboratory.

Courtesy of Dr Stephen Hunt

Unfortunately, the temporary planning arrangements ceased, leading to the end of Graham and Fran’s experiment in low-impact living. Street Farmhouse was dismantled in October 1975. However, Graham’s adventures in sustainability were not over. In 1975, he took off with friends in a van to the Portuguese Revolution, responding to a request for mutual aid by installing solar technology near Setúbal. During the late 1970s, he established an independent urban farm in Thamesmead. In 1984, he moved to the West Country, where he worked on many alternative architecture projects with the Bristol Gnomes and was instrumental in setting up the self-build community at St Werburghs. The last time I caught up with Graham, then Septuagenarian, he was still shaking off the sparkle from a rave in Berlin. Sadly, he died in 2018. Fittingly, he went out in an eco-friendly wicker coffin to the sound of Jefferson Airplane’s “When the Earth Moves again” and a mighty blast of techno.

Was Street Farmhouse the first ecological house? So far as I know, that claim stands.

Stephen E. Hunt (@DrStephenHunt) is a writer, university academic support coordinator, and member of the Bristol Radical History Group (@BrisRadHis). His PhD in English Literature was awarded for a research thesis on Romantic ecology at the University of the West of England. He continues to research within the ecological humanities. Stephen’s books include: The Revolutionary Urbanism of Street Farm: Eco-Anarchism, Architecture and Alternative Technology in the 1970s (Tangent, 2014); Ecological Solidarity and the Kurdish Freedom Movement (editor and co-author, Rowman & Littlefield, 2021); We Must Begin with the Land: Seeking Abundance and Liberation Through Social Ecology (pending Zer0 Books).

The Building of the Month feature is edited by Andrew Murray (@aaamurray)

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.