This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

June 2024 - Swanlea School, Tower Hamlets

Image credit: Swanlea School

Swanlea School, London Borough of Tower Hamlets (1993)

Percy Thomas Partnership with Hampshire CC Architects Department, YRM Anthony Hunt Associates (structural engineers) and Whitby & Bird (services engineers).

By Robin Bishop

Swanlea School is one of London’s best late modern schools – but frustratingly, only a bird or user of the London Hospital tower can see how confidently it straddles its quarter of Whitechapel. It exemplifies a wave of schools built in the 1980s and 90s to exploit solar energy. In England alone, dozens were built with atria, conservatories and other passive features.

The immediate driver of solar schools was the oil price-rise triggered by the Arab-Israeli war of 1973, before most of the UK’s North Sea oil fields were onstream. It coincided with growing awareness of the limitations of postwar schools and their mounting maintenance costs.

The benefits of judiciously controlled solar energy for schools weren’t news. From the 1870s London and other board schools used generous glazing to help warm classrooms in winter. Interwar open-air schools and postwar systems-built schools usually orientated classrooms southerly. St Mary’s School of 1961 in Wallesey was heated entirely from solar energy.

Image: Robin Bishop

Image credit: Architects’ Journal, 20 October 1993

Schools were one of the biggest public sector users of energy. Since the 1950s, the Architects & Building Branch (A&B) of the Department of Education & Science (DES) had played an influential role in design of school buildings. It researched educational and architectural best practice and produced Building Bulletins (BBs) on many aspects of school design. In the early 1980s it undertook a number of research and development projects to improve school energy efficiency. These included energy-efficient refurbishments of Victorian schools, trials of heat pumps and the publication of Energy Design Values (EDVs) for new school buildings. It also took a close interest in passive solar features to reduce energy usage.

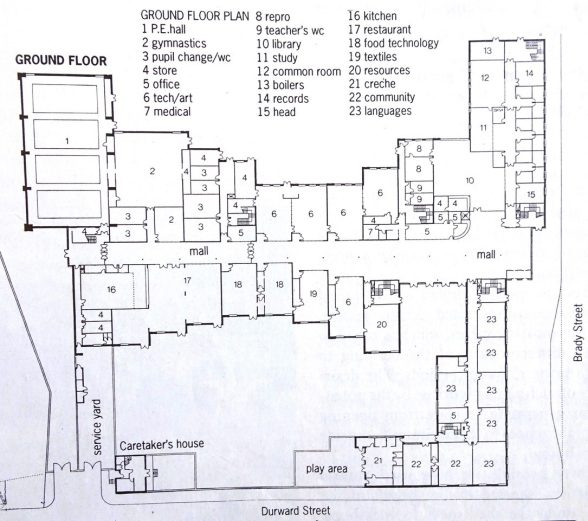

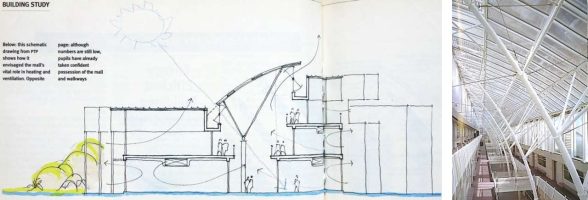

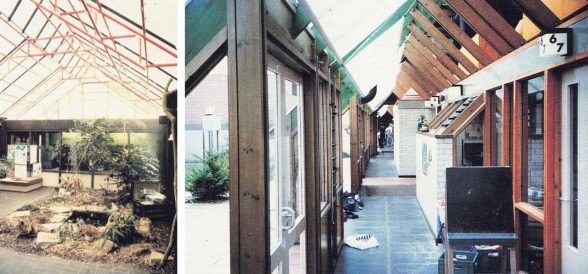

Swanlea, opened in 1993 for 1,050 secondary-age pupils, exhibits the passive solar approach spectacularly. A dramatic 3-storey, south-facing glazed mall runs 127 metres east-west the length of the building. Classrooms and other accommodation cluster along its north and south sides beneath perky segmental curved roofs.

Image credit: Building, 24 September 1993

Swanlea was the culmination of Hampshire County Council’s thinking about passive solar schools. Although Tower Hamlets Local Education Authority (LEA) was the client and Percy Thomas Partnership the lead architects, the concept design evolved in collaboration with a team led by Hampshire’s chief architect Colin Stansfield Smith. It was developed by architect Ron Morgan.

Hampshire had long been exploring passive solar systematically, with both in-house and independent engineering expertise. As well as lower energy bills, it offered the possibility of more floorspace. The DES funded a minimum teaching area (MTA), plus a proportion of non-teaching area. Additional area was sometimes paid for by LEAs. Because atria and conservatories were unheated (except by the sun) they offered valuable extra floorspace at lower building cost.

Image credits: Robin Bishop

In 1980 Newlands Junior School (architect Mervyn Perkins) opened with a large elegantly-roofed central atrium. It provided cheap circulation space between a south-facing classroom wing and the hall and other spaces to the north. Attractively planted, it also formed a welcoming exhibition area and social space for dropping off and picking up children. As well as enabling a teaching area 20% above MTA, the atrium was estimated to save 23% of the building’s heat loss.

Four years later, Netley Abbey Infant School (architect Dennis Goodwin) was more radical. Most of the south-east wall was enclosed by a conservatory for circulation, sand and water play. During the heating season the sun pre-heated air that was circulated via roofspace ducting to classrooms. The cost saving in Netley’s gas consumption was estimated at 35%. With relatively few external windows, however, poor ventilation was an issue. The linear conservatory also proved difficult to supervise and too narrow for much practical activity.

Through these and other projects, Hampshire acquired a reputation for engineering innovation as well as architectural bravura. In practice, its atria and conservatories sometimes underperformed as educational spaces, but this was more than offset by the light, airiness and spatial delight that they brought to school design.

Swanlea was one of the most ambitious of the passive solar school wave, founded on sound educational space planning and responding sensitively to its tight urban site. Technical triumphs include the curved masts and raking struts supporting the mall roof, and the ‘Okasolar’ prismatic glazing that reflects most of the sunshine in summer and transmits most of it in winter.

Recent anecdotal evidence indicates that the central mall makes a pleasant visual impact, but is little used except for the cafeteria, and saves heating costs less than expected. More predictably, structural checks, glazing and fire vent repairs are expensive to carry out. Despite these technical challenges and being in one of the nation’s most deprived areas, Swanlea has consistently been among the highest-performing state schools.

Image credit: Historic England

Swanlea contrasts starkly with Perronet Thompson Secondary School in Humberside, opened five years earlier. With 1,200 pupils, it also housed a public library, theatre and other community facilities for the vast Bransholme estate. Its architects, Humberside Property Services Department, described it (in Building 27 January 1989) as “like a silvery spaceship ready for take-off…[with] a ‘Tardis’ quality about the building since it contains much more accommodation than the comparatively simple external envelope would suggest.”

Perronet Thompson had no fewer than seven unheated atria and a 4-storey, south-facing conservatory, as well as active warm air reycling. Fuel savings of 30% were expected. Despite initial popularity with pupils, however, it revealed serious design weaknesses. Its complex plan made pupil supervision difficult, and its internal environment was uncomfortable in both cold and hot weather. Pupil behaviour deteriorated, numbers on roll halved and it was put into ‘special measures’. Closed in 1999, it reopened as Kingswood High School but was demolished in 2011.

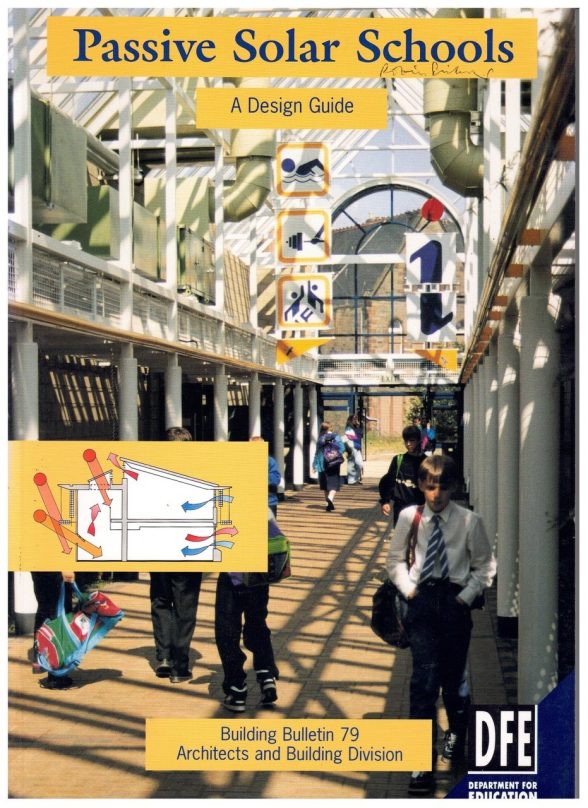

Image credit: Lothian Regional Council, Department of Property Services

These schools featured in a review by A&B of passive solar projects in the early 1990s. Led by Head of Engineering Mukund Patel, Cranfield University was commissioned to study 36 schools. Three were in Scotland; the rest in England. The environmental performance and running costs of 17 were then monitored over a year. As well as atria (i.e. Newlands) and conservatories (i.e. Netley), the case studies included a school with Trombe-Michel walls (Looe Junior & Infant School) and one with thermo-syphoning air panels (Nazeing County Primary School). Swanlea opened too late for its post-occupancy performance to be evaluated.

Results were published in 1994 as Passive Solar Schools: A Design Guide (BB 79). Its overall conclusions were clear: schools with passive solar features need not cost more than ordinary schools; and a good passive solar design can reduce energy use by at least 10%. It included sensible recommendations about orientation, dimensions, ventilation, shading and the like. Many of the more successful passive solar features were adopted in schools built as part of the DfE’s subsequent Academies and Building Schools for the Future Programmes.

BB 79 showed that government and some LEAs were ahead of the game in recognising the challenges of energy conservation and responding inventively to them. Passive solar techniques turned out to be of limited value on their own, but combined intelligently with onsite power generation and other active technologies, and controlled by computerised building energy management systems, they are now mainstream in new buildings.

Robin Bishop is a former architect, teacher of architecture and C20 Society member. While at the Architects & Building Branch of the DfE, he worked on BB 79 with Mukund Patel (former Head of A&B Branch) and Richard Daniels (Environmental Engineer), both of whom contributed to this article.

Building of the Month is edited by Joe Mathieson; an Architectural Adviser at the Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust, writer and C20 volunteer.

For pitches, or to discuss ideas for entries, please contact: joe@c20society.org.uk

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.