This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

November 2020 - The former North Peckham Civic Centre, London Borough of Southwark

Credit: Southwark Local History Library & Archive

F. O. Hayes, with T. G. Bell, K. Dean and Muriel Jamieson, 1966

Amma, the heroine who opens Bernadine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other, a once-renegade black feminist playwright, is now enjoying new renown with a sold-out run at the National Theatre. Evaristo’s narrator tells us she grew up in Peckham in the 1970s and 1980s. Fleshing out her untold story, it figures that the North Peckham Civic Centre would have been formative to her artistic development (and Amma would have read its lively programme in her copy of Spare Rib). As the Peckham Society put it, the Centre “filled a void in the local community by providing live entertainment”. Highlights included: regular fixtures, like the pantomime season, the Kwanza African Christmas Festival, and the Starlight Cabaret; and new theatre, comedy, dance and music—memorably the 1993 comedy season headlined by Lily Savage and ballet nights with the Southwark Concert Orchestra. The Centre also offered the spaces needed to support local groups like the Women’s Equality Unit of Southwark and the Southwark Irish Forum. It launched the Southwark AIDS and HIV Booklist in 1990. In short, the Centre helped lay the foundations for Peckham’s now-celebrated cultural infrastructure, and was the forerunner to Alsop and Störmer’s Peckham Library (2000).

Credit: Southwark Local History Library & Archive

A corner-stone of south-east London’s post-war municipal development, the Centre occupies a corner spot on a quarter of an acre, between the Old Kent Road and Peckham Park Road, originally alongside warehouses and a then-still-functioning Surrey Canal. It is the C20 highlight in a cluster of heritage assets in the area (plotted here for the London Architecture Festival), disappearing at a mortifying rate. While it is now rented by the Everlasting Arms Ministry Pentecostal church, ghost marks of the words “The Civic”, its affectionate moniker, can still be discerned on its main elevation. Rooting the building in its locality, Adam Kossowski’s Grade II-listed chromatic mural tapestried around it adds to the story of civic panache.

John East

The Centre was built in 1966 by Southwark council, newly incorporating three metropolitan boroughs. It was a progressive move to bring together theatre, public events, plenum, debate, meeting spaces and a public library—the latter absorbing the Camberwell Public Library (R. P. Whellock, 1890)—into one prominently located building, concretising the then popular idea of a “civic centre”. It was built by the council’s own architecture and planning department under F. O. Hayes who had previously led Camberwell’s team overseeing what Pevsner and Cherry called “the most consistently interesting housing” in South London, such as Sceaux Gardens (1959). Kate Macintosh, who wrote to me, described him as “patrician … a tall handsome man with a fair measure of personal dignity who was well respected by staff”.

Credit: Southwark Local History Library & Archive

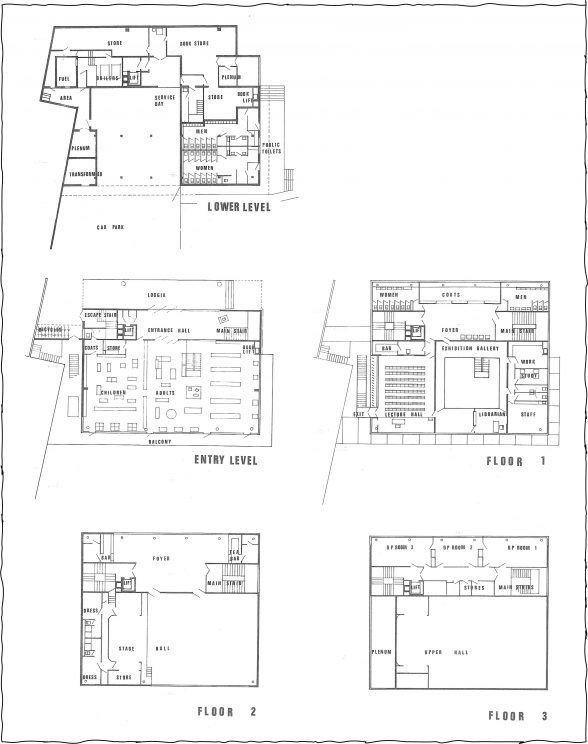

Four problems informed the Centre’s design: a steep incline in the land from the NW to the SE corner, a high water table due to the canal, and the dangers and noise posed by traffic. The resulting building is a large yellow brick box, deftly fenestrated, which rises above a dark brick plinth over four principal stories. The lower floor, exploiting the incline, is partially sunken. It housed a car park, loading bay, a book store, services, and public conveniences. On the floor above, the entrance is set back behind a loggia to alleviate traffic noise. One enters the building up a short flight of steps—not directly, but laterally from either of the two roads onto which it sits, to help keep visitors safe from traffic. Wrapped around this floor is a cantilevered sun-shielded terrace, originally containing furniture designed by Hayes.

Credit: Southwark Local History Library & Archive, adapted by Joshua Mardell 2020

The entrance leads in to a double-height space originally occupied by the library and enveloped on three sides by the exhibition gallery on the first floor. Bryan Kneale’s mobile of the Camberwell Butterfly was hung here, emphasising spaciousness. Kneale was already of international renown in 1966, and had a major retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery that year; an interview with Kneale is available here. The Council’s press release on the Centre, still echoing the spirit of the Festival of Britain, made it clear that its artworks were “conceived as an integral part of the building”.

At first-floor level there is a large lecture hall with a seating capacity of 100 along with cloakroom facilities, toilets and offices. The second-floor foyer on the road side acts as another sound barrier. It leads onto the double-height assembly room which seats 400 people with its own stage, dressing rooms and stores. It is lit from the south by narrow vision windows and from above by six rows of monitor lights. Its walls, as with most of the Centre, are of light-coloured ash panelling which still survives, hidden by white paint. The third floor comprises the upper-part of the assembly hall, the plenum chamber and three committee rooms, designed to be used either independently or en suite. The roof originally contained the keeper’s two-bedroom apartment, and around its perimeter was a track for mounting a (surviving) gondola over the building’s edge to facilitate cleaning.

Credit: Ulrike Steven

The Centre is of a more intimate scale than those one normally associates with the building type (it’s akin to the recently demolished Rotherhithe Civic Centre by Yorke Rosenberg & Mardall, 1975). The Surveyor and Municipal Engineer (December 1966) noted how well it was received when it opened and how it proved to be “an appreciated addition to the amenities of the London Borough of Southwark”. Described as a local “landmark” by Pevsner, it is still well-regarded today. Alongside the Architects’ Co-Partnership’s Dunelm House in Durham and Rosemary Stjernstedt’s Central Hill Estate in Lambeth, Docomomo included the Centre in their Buildings at Risk register, arguing that it is “made up of elements that could warrant its appearance on the front pages of any current architecture magazine”.

Credit: Ulrike Steven

In The Architecture of Public Service (2019, ed. Harwood and Powers), civic centres are identified as among the main architectural losses in recent decades, threatening “our civic architectural legacy” as a whole. Sadly, the former North Peckham Civic Centre is no exception. This article may come to represent a valedictory lament for a happy, colourful and considered building—for it is due to be demolished anon.

Dr. Joshua Mardell edits the Building of the Month for the C20 Society. He is currently the Research Collections Fellow at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art

Contact: joshua.mard311@gmail.com

Southwark Council approved the application for demolition and redevelopment (and the relocation of the mural), subject to Mayoral referral outcome, on 5th November 2019.

Peckham Weeklies and what if: projects have run several tours of the Old Kent Road’s diverse heritage. | Vital OKR mounted a campaign to save the Civic Centre in 2017. | Students of the Degree Design unit at the Cass Architecture School in 2016/17 studied the centre as part of a project on the Old Kent Road Opportunity Area.

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.