This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

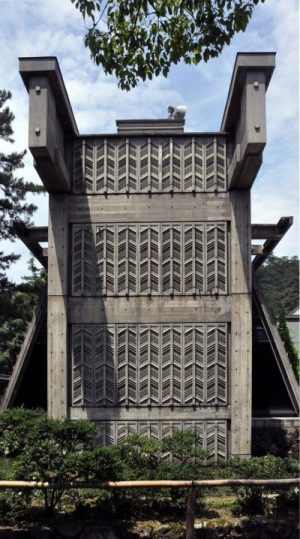

October 2016 - The Izumo Grand Shrine Administrative Building, Japan

by Neil Jackson

The city of Izumo (population 146,000) is in Shimane Prefecture, a still remote and under-populated area located on the north coast of Honshū, the main Japanese island, facing the Sea of Japan. The Chūgoku mountains to the south squeeze the Prefecture into a narrow coastal strip which runs from the capital, Matsue, to the north, down to Masuda in the south. When approached today by train, it is by a single-track line which runs through the mountains and the jungle. Yet here, despite or rather because of its remoteness, is the Izumo Grand Shrine.

Located where an important kami (or divinity) resides, Shintō shrines are often found, unlike Christian cathedrals in Europe, far from the centres of power such as Nara, Kyoto and Kamakura. The Izumo Grand Shrine is thought to be the oldest Shintō shrine in Japan although its extant buildings date from only the mid-eighteenth century. It predates the Ise Grand Shrine in Mei Prefecture, which is dedicated specifically to the Emperor, and enshrines the kami Ōkuninushi, the deity of marriage who, it is believed, created Japan even before it was populated by the Emperor’s ancestors. Its remoteness has led to it being overshadowed by other more recent and accessible Shintō shrines but the myth remains that in October all the Shintō gods meet there.

In or about 1962, Choemon Tabe, the President of the Supporting Board of the Izumo Great Shrine, who also happened to be the governor of Shimane Prefecture, asked Kiyonori Kikutake (1928-2011), then most recently associated with the Metabolist group, to design a new, fireproof Administrative Building to replace the one that had burnt down. In the same way that Kenzō Tange had represented, in reinforced concrete, traditional Japanese timber buildings at the Kagawa Prefectural Government Building at Takamatsu on Shikoku (1958), so Kikutake used concrete here at Izumo. However, his choice was for post-stressed concrete since he felt that in-situ concrete would make the sacred area dirty. The use of this modern material to emulate traditional building forms was one of the solutions promoted by Tange and others during the debate on Tradition versus Modernity which was challenging Japanese architects at this time. Put simply, the reproduction of traditional architecture would recall the great disaster of the Second World War while the adoption of Modernist architecture would be an acknowledgement of the conquering Western powers. Thus the representation, through simile, of traditional Japanese building forms and techniques in modern materials, whether concrete or steel, was an acceptable compromise.

In or about 1962, Choemon Tabe, the President of the Supporting Board of the Izumo Great Shrine, who also happened to be the governor of Shimane Prefecture, asked Kiyonori Kikutake (1928-2011), then most recently associated with the Metabolist group, to design a new, fireproof Administrative Building to replace the one that had burnt down. In the same way that Kenzō Tange had represented, in reinforced concrete, traditional Japanese timber buildings at the Kagawa Prefectural Government Building at Takamatsu on Shikoku (1958), so Kikutake used concrete here at Izumo. However, his choice was for post-stressed concrete since he felt that in-situ concrete would make the sacred area dirty. The use of this modern material to emulate traditional building forms was one of the solutions promoted by Tange and others during the debate on Tradition versus Modernity which was challenging Japanese architects at this time. Put simply, the reproduction of traditional architecture would recall the great disaster of the Second World War while the adoption of Modernist architecture would be an acknowledgement of the conquering Western powers. Thus the representation, through simile, of traditional Japanese building forms and techniques in modern materials, whether concrete or steel, was an acceptable compromise.

Kikutake, however, explained the form of his building through the use of metaphor. If the Honden, the most sacred building at the Izumo Great Shrine, were regarded as the warehouse of the god, then the Administrative Building could be seen as the Inakake, the temporary rectangular framework erected in the paddy fields where the rice crop is hung to dry. Thus the external walls, canted so as not to allow the building’s scale to overwhelm the main shrine, represent the drying rice and thereby invoke the memory of a typically pastoral Japanese scene.

The use of two post-tensioned reinforced-concrete beams allowed Kikutake to create a large, uninterrupted internal space measuring 10m by 45m. The beams, which run the length of the building, are supported at each end by reinforced-concrete columns creating the form of a torii or Shintō gateway. Against these the louvred side wall lean allowing the light to gently flood the interior. Concrete roof beams, which are exposed internally, protrude along the length of the eaves while the end walls are infilled with decorative concrete panels suggestive, perhaps, of the drying rice paddy. Whereas the east side of the building presents a uniformly sloping elevation, the west side twists and turns to accommodate internal spaces, as if the paddy is momentarily frozen by an icy wind. Internally, the space in subdivided by a mezzanine floor with a glazed space above although the greater part of the interior remains open.

The Administrative building was recognized immediately following its completion and was awarded the 5th AIJ Award by the Architectural Institute of Japan. The following year it received the 7th Pan-Pacific Award of the American Institute of Architects as well and the Japanese Minister of Education’s Award for Fine Arts. In 1965, it won the Building Contractors Society Award from the Japan Federation of Construction Contractors. More recently, the DoCoMoMo Working Group, a sub-committee of the Architectural Institute of Japan’s Architectural History and Design Committee, chose the building as one of 100 most representative modern buildings in Japan. It was shown in the exhibition Modern Architecture as Cultural Heritage — the DoCoMoMo 100 Selection at the Shiodome, Tokyo, in 2005 and included in the special Japan Architect 57 issue of the same year. There is no doubt, therefore, that this building, recognized nationally and internationally, is of significance. However, those who manage the building intend to demolish it because, and for no other apparent reason, the roof is leaking.

To say that the roof is leaking is, of course, to belittle the problem. It might be much greater than that. There could be serious internal damage to the post-tensioned concrete beams; there could be extensive damage internally; or the building simply could be redundant. Yet in the campaign to preserve the building promoted by DoCoMoMo Japan and also by ICOMOS, no other reason for the building’s demolition has been identified. In March 2016, Hiroshi Matsukuma, the President of DoCoMoMo Japan, wrote to the Rev. Takamasa Senge at the Izumo Great Shrine, saying, ‘The Administrative Building of the Izumo Great Shrine is, above all, indispensible to the history of Japanese modern architecture’ and appealed for its preservation. The ICOMOS Press release of 9 September 2016 stated that ‘The committee has strongly encouraged the Shrine authorities to seek a positive conservation outcome for this item of Japan’s modern heritage’ and that ‘ISC20C has offered to work with the Shrine to help find a satisfactory outcome for all concerned.’ Others, including Bryan Clark Green, Chair of the Heritage Conservation Committee of the (American) Society of Architectural Historians and Enrique Xavier de Alanis, Vice-president for Latin America of the ISC20C, have written to support the preservation of the building.

The case for conservation, however, is a difficult one to make. This is not because it cannot be argued reasonably, nor because there is any lack of supporting evidence, but because, I believe, it is something contrary to the Japanese psyche. The value of property in Japan is not in the building but in the land. Therefore it is not unusual to demolish and rebuild your house on the same site rather than to move to a larger (or smaller) house in another district. This thinking was, in fact, fundamental to the work of the Metabolists: consider Kikutake’s own Sky House in Tokyo (1958) which has grown and shrunk, over the years, with the size of the family. There is a lot to be said for this, especially in terms of social cohesion and community stability. Furthermore, the Japanese will move a building if it is thought worth preserving: it is the building, like an art work, rather than the context which is acknowledged. This was the fate of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel in Tokyo (1923), part of which, following demolition in 1968, was rebuilt at the Meiji Mura outdoor architectural museum near Nagoya. You can see it there — even take tea there — along with about seventy other relocated buildings. The traditional Japanese house has always been a temporal affair. Lightweight and frail, it could be as easily destroyed in an earthquake or, more likely, in the fires that followed, as it could be rebuilt again on the same site a few days later. In the same way that at Ise, where the shrines are demolished every twenty years and rebuilt or reincarnated in perfect facsimile on the adjacent site, so the Shintō religion teaches that every human has an eternal soul or spirit and that, after death, the spirits inhabit the other world where deities reside. So it is with architecture. To have a post-stressed concrete building at a Shintō shrine is, therefore, rather a contradiction in terms. For of all modern architectures, it is perhaps the most permanent.

If Members of the Twentieth Century Society would like to add their voices to the debate, they should write to (Rev.) Takamasa Senge, the Izumo Grand Shrine, 195 Kitsukihigashi, Taisha-machi, Isumo-shi, Shimane-ken, 699-0701 JAPAN.

Arigatōgozaimashita (Thank you).

Neil Jackson

Charles Reilly Professor of Architecture, University of Liverpool in London

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.