This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

February 2023 - The Law School Building, University of Western Australia, Perth

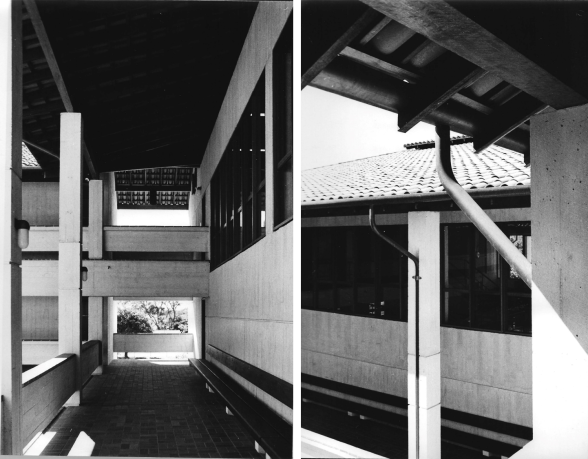

Photographer: R.J. Ferguson, Source: Ferguson Architects Archive

The Law School Building, University of Western Australia. Whadjuk Noongar Booja (1967)

R.J. Ferguson and Gordon Stephenson, Architects in Association. Project Architect: R.J. Ferguson.

The architect of the Law School Building, Ronald Jack (Gus) Ferguson was born in 1931 in Kalgoorlie, the land of the Wangkatja people, a gold mining town located 600 kilometers east of Perth. He and his family then moved to Boorloo (Perth), the capital city of Western Australia, where he commenced his studies in architecture at the recently opened Perth Technical School. Upon graduation, in 1957 he and his wife Clare embarked on a lengthy working holiday, heading first to Africa where they spent a year working, before making their way to London. Here he found work with Chamberlin, Powell and Bon. Ferguson spent 18 months working closely with Joe Chamberlin on the Barbican scheme before he and Clare drove home to Perth. This was a six month long journey together with Michael Neylan, Peter Deakins and Liz Vercoe from the CPB office following the overland trail. This period of working and travelling was to be formative for Ferguson and would fundamentally alter his approach to the architecture.

Photographer: R.J. Ferguson, Source: Ferguson Architects Archive

Once back in Perth, Ferguson received his first major commission almost immediately. The Hale School Memorial Hall (1961) was the first off-form concrete building in Australia and it attracted significant attention from the profession when it was awarded the RIBA Bronze Medal in 1963 by a jury convened by British planner Gordon Stephenson. Stephenson had recently immigrated to Perth and had been installed as the Consultant Architect at the University of Western Australia. Stephenson clearly saw something in Ferguson and so invited him to design the new Law School for the University. It was to be one of a group of four buildings intended to consolidate and invigorate the physical development of the University of Western Australia, responding to the strong Mediterranean character of the campus established by the original Hackett Memorial Building group (1932) designed by Conrad Sayce and Rodney Alsop.

Photographer: R.J. Ferguson, Source: Ferguson Architects Archive

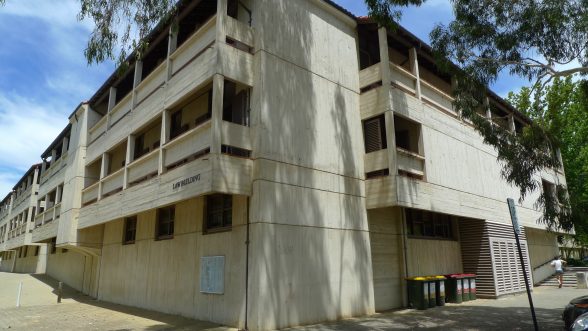

As constructed, the Law School is a three-storey rectangular building, designed around large central courtyard space. External walkways ring this courtyard space which provide access to all classrooms and offices. Complete with a ‘martini glass’ fountain, the courtyard provides both light and natural ventilation to all the rooms. Using a deeply textured, golden off-form concrete and Cordova roof tiles, the Law School echoes the limestone walls and terracotta roofs of the original campus buildings, while reflecting Ferguson’s interest in vernacular architectural traditions seen on his travels. The building conjures the spatial excitement and vitality of the Greek islands and the layered composition of Italian hill side villages, offering a place of refuge within the university campus. There are variety of idiosyncratic, hand crafted details, ranging from the use of whole tree trunks as formwork on the projecting stairwells, to the imprinting of various symbols, signs and patterns directly into the concrete. A series of cast brass plugs, hand carved by Ferguson with the faces of Greek gods, including Zeus, were used to cover the conduit junction box opening, but were all quickly stolen after the building opened.

Image: Andrew Murray, 2018

The Law School is perhaps not as consciously sustainable as other buildings to be featured in this year’s column and perhaps an odd choice to begin with. But in its low-tech approach and deliberate harmony with its immediate environment, it offers a considered mediation on what it means to build in particular place and to work carefully with a particular climate. Perth has a Mediterranean climate, with hot and dry summers and mild, wet winters. Through the evocation of a simple Mediterranean lifestyle, lived mostly outdoors, with plenty of access to fresh air, an abundance of shade, and thick thermal mass to envelope you, the Law Building provides a compelling, and almost inevitable, response to building in Perth. Rather than resisting it and attempting to filter it, the Law School lets the environment simply pass through it. It is always present. The building was designed to be naturally ventilated and cooled which was unusual for a large, modern faculty building. The classrooms and office spaces are all accessed from an open-air corridor which rings the central courtyard.

Photographer: R.J. Ferguson, Source: Ferguson Architects Archive

External balconies wrap the building, with large openings fitted with timber shutters allowing a strong cross breeze to pass through the classrooms. With doors banked along each side, the rooms are flushed with fresh air, drawn in through the courtyard and out through the balconies, making the most of the strong breezes which would come in off the Derbal Yerrigan (Swan River), just 100m away.

Each door has a large openable panel above allowing privacy for the classrooms, while maintaining a constant intake of fresh air. The projecting balconies not only allow cross ventilation, but they shade the windows, the walls and the classrooms themselves, providing further refuge from the strong summer sun. Ferguson drew on his recent travels through the Mediterranean and Africa to provide a complex layering of space within the building, with a focus on the importance of offering large, shaded areas to retreat from the sun, while providing dynamic views across the building. The design means that the occupants are aware of the climate and its fluctuations at all times, there is little mediation between inside and out. The Law School was a major success and led Ferguson to design an enormous number of buildings for UWA, all of which continued this dialogue with the natural environment and provide a layered sequence of open and shaded spaces which unfold across the campus.

Image: Andrew Murray, 2018

Andrew Murray is a caseworker at C20 and has recently completed his PhD at the University of Melbourne which looked at the relationship between Britain and Western Australia and its effect on the architectural culture of Perth in the 1950s. He has previously been the editor of The Architect WA and The Weather Ring. @aaamurray

Image: Andrew Murray, 2018

Look for past Buildings of the Month by entering the name of an individual building or architect or browsing the drop down list.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.