This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Photo: James O Davies/Historic England

A little church with a fascinating history

This church was not only an example of new liturgical thinking, but also a social experiment and a piece of innovative technological design. Unfortunately, it is now under threat of demolition. It’s at the centre of the Blackbird Leys housing estate in SE Oxford, developed by Oxford City Council in 1953–58 to house workers employed by the growing car industry. It provided 2,800 new homes. As the first houses were occupied, the Church of England decided that the estate was too big to be served by the existing parish of Littlemore, and should be designated as a district in its own right, with its own church. By 1960, a temporary building – essentially a wooden hut – had been erected, which doubled as a community hall.

The new permanent church was funded and built by the Church of England, but soon after completion it became one of the first Local Ecumenical Projects in England, and one of the first churches used by both C of E and Non-Conformist congregations, holding services at staggered times. The Sharing of Church Buildings Act 1969 was a pioneering initiative which still functions, jointly funded by the different denominations. As a result, this church is outside the regulation of any of the major denominations, and subject to the same planning laws as secular buildings.

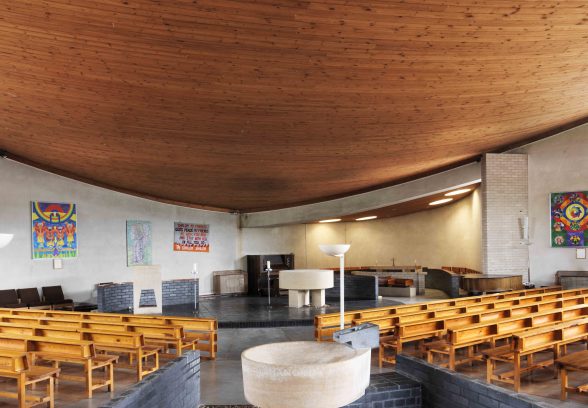

The innovative design, by Colin Shewring, is a very important example of a church designed according to Liturgical Movement principles, with a forward-placed altar, fan-shaped seating and peripheral choir. A prominent feature is the sanctuary, an egg-shaped area with a circular altar flanked by the pulpit, a reversion to very ancient Christian practice. The distinctive floor textures (including cobbles) reflect the differing functions of the baptistry and sanctuary while including them in one inter-connected space. Shewring developed the design in close cooperation with the local congregation, who wanted the altar, pulpit and font to be visually linked, with simple geometric shapes of a pale colour against the dark grey engineering bricks. They wanted to emphasise the combined value of the sacraments – the Word (pulpit), baptism (font) and communion (altar). A quiet ambience and concealed lighting were also priorities. All were enclosed in an innovative embracing volume that Elain Harwood has described as ‘kidney-shaped’. To Pevsner, this was ‘the 1960s at its most radical’.

The building also features a rare timber hyperbolic paraboloid roof by Hugh Tottenham, who designed the first such roof in Britain, the weaving shed of the Royal Carpet Factory in Wilton (1957, now demolished) while working at the Timber Development Association. In 1959 he set up his own engineering practice and went on to design several other hyperbolic paraboloid roofs, including one for St Peter, Ravenshead, Nottingham (Grade II) also with Colin Shewring. The roof shape was integral to the interior design of the Church of the Holy Family. Shewring explained that the inverted dome-shaped roof was lower over the altar and pulpit so that it acted as a large sounding board. Unfortunately, this unusual roof has suffered from a number of problems in recent years.

Unchecked leaks have caused deterioration to the point where the church has been abandoned. The church sits on a large site: there is a priest’s house and – until a lack of funds prevented them – there were plans for a hall and classrooms as well. This year, the local congregation decided to apply to demolish the church and priest’s house, and build a new church centre, funded by new flats alongside. The Church of the Holy Family is an important church which, as well as being both liturgically and technologically innovative, remains remarkably intact. We think that the roof problems could be solved, funded by the income from the proposed flats, and have asked Historic England to list the church, in the hope that this heart-shaped gem of a building can be retained, repaired and brought back to life.

Clare Price

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.