This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

‘The No 1 Poultry site posed an overwhelming question at the level of representational form in three ways’, wrote Colin St John Wilson in 1998. ‘Firstly the primacy of its location in the city required that an exceptional statement should be made; secondly propriety demanded that this statement respond to the individual nature of its extraordinary ring of neighbouring buildings; and thirdly it should match up to the level of visual variety and character of the listed incumbents on the site… If we imagine a baton passed from Wren’s St Stephen Walbrook to Dance the Elder’s Mansion House, then to Soane’s Bank of England and thence to Lutyens’ Midland Bank, which architect would be capable of concluding the sequence without fumbling it? Without question there was only one conceivable choice – James Stirling and his partner Michael Wilford.’

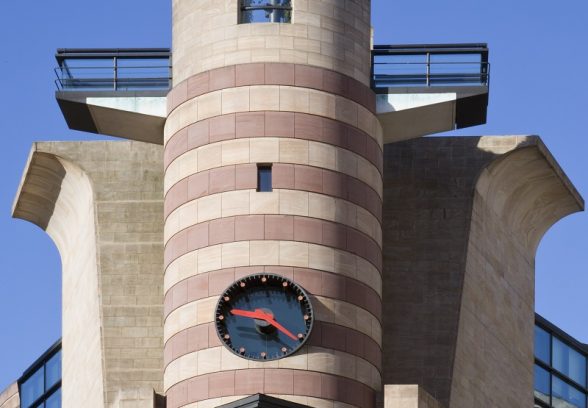

Step up out of Bank tube station in the heart of the City and you can’t miss this playful, monumental, stripy building on a highly prominent triangular site, surrounded by historic buildings including the Bank of England (Soane), the former Midland Bank (Lutyens) and St Mary Woolnoth (Hawksmoor). Once likened by Prince Charles to an ‘old 1930s wireless’, No 1 Poultry is a remarkable 1990s speculative office development complete with ground-floor retail colonnades, five floors of office space and a landscaped roof garden and restaurant. It was designed by Sir James Stirling, one of Britain’s most significant 20th century architects, and the contextual design, rigorous attention to detail, high quality materials – including sandstone cladding from Australia – and incorporation of public realm spaces make it one of the most important examples of post-modern architecture in Britain.

Prompted by proposals from the owners to extend and alter the principal facades, we have submitted an urgent listing application to Historic England. Because the building is under 30 years old, it is eligible for listing only at Grade II* or above – a high bar, but one we believe it easily meets. We want to protect this building – virtually unaltered since completion – from harmful changes, but we also hope the assessment will trigger a wider evaluation of post-modern architecture, a style which is only just beginning to be studied and understood in historic terms. This building in particular (its reputation initially marred by the demolition of previous historic buildings on the site) deserves a fresh appraisal.

Our listing application has received wide-ranging support from high-profile architects, architectural critics and academics, including Lord Rogers, Lord Foster, Zaha Hadid, Piers Gough, Charles Jencks, Hugh Pearman, and Mark Swenarton, Emeritus Professor of Architecture at the University of Liverpool. A total of twenty-four members of James Stirling Michael Wilford and Partners’ original office have also written in support, including Laurence Bain, the responsible partner architect throughout the project. The former owner, Lord Palumbo, is also fully supportive of our listing application. We have been given full access to the architects’ project archive which contains detailed descriptions of the original design, Stirling’s design statements and evidence to the public inquiry, the Planning Inspector’s report and the Secretary of State’s decision letter.

A long history

It was in 1985 that James Stirling Michael Wilford and Associates was commissioned to design a mixed-use office building in the heart of the City of London. This prestigious site, bounded by Poultry, Queen Victoria Street and Sise Lane, was a mix of Victorian commercial buildings, eight of which were listed, and lay within a Conservation Area. The Mappin & Webb building at the prow of the triangular site was the most impressive.

The site already had a history of planning battles. A previous proposal by Lord Palumbo, who had invited Mies van der Rohe to design a tower and plaza on the site in 1967, was refused consent after a public inquiry, but on appeal the Secretary of State said that he ‘did not rule out redevelopment of the site if there was an acceptable proposal for replacing existing buildings’. By 1986, Stirling Wilford had prepared two schemes, both on a smaller site than the Mies proposal: scheme A, which retained the Mappin & Webb building, and scheme B, total redevelopment. After negotiations with the Corporation of London, scheme B was chosen, but the previous controversy and concerns over the loss of the Victorian buildings led to another public inquiry. Conservation groups and English Heritage were at loggerheads with the developers, but in October 1988 scheme B was approved by the Secretary of State. A further two years of legal argument was finally resolved when five law lords confirmed his decision. After yet another public inquiry in 1993, the Department of Transport agreed to close Bucklersbury, a narrow road crossing the site. Construction began in 1994 and was completed in 1997.

According to Laurence Bain, the brief called for a prestigious headquarters office building which could also accommodate a large number of pedestrians at street level, access to Bank Underground, a public walkway across the site, and the maximisation of shop frontages on Poultry and Queen Victoria Street.

As Stirling pointed out in his evidence to the 1988 inquiry, there are clear links between the historic context and No 1 Poultry, and the axial arrangements and symmetrical forms of the buildings at Bank are referenced in his design. As most of the surrounding buildings were eight storeys high, it had two levels of retail, five of offices and a roof garden. The weighty presence of the Bank’s strongly articulated stonework and the Mansion House’s huge classical columns led to Stirling’s use of stonework and articulated courses and large-scale architectural elements. ‘Its dialogue with its neighbours is an essential consideration,’ he told the inquiry in 1988. Details from the previous buildings were carefully incorporated, like the terracotta frieze of royal progresses on the Poultry elevation, and the clock from the Belcher Mappin and Webb building above the office entrance in the courtyard.

High praise

Stirling’s geometric rationale was critical. The 1998 inquiry inspector said that the proposals ‘by their dignified order, their imaginative ingenuity and pervading overall consistency, would contribute more both to the immediate environment and to the architectural heritage than the retention of the existing buildings. The new building would to my mind be of substantial importance for the present age… To suggest that a building by James Stirling would be acceptable elsewhere in the city but not here, would in my opinion be to miss once again that vital opportunity. The loss would be all the greater because it would be of a considered mature work by a British architect of international stature of whose achievements the nation can be justly proud… Taken overall, as far as the public domain is concerned, I would say the design has strong consistency and character and is one which would be a worthy modern addition to the architectural fabric of the City. It might just be a masterpiece.’

No 1 Poultry is a controversial building because of its flamboyant and apparently irreverent style, as well as the lengthy battles over its construction. The choice of materials, the careful reference to its historic context and the precise geometrical interplays make it stand out as a remarkable and confident work. In our view, it is one of Stirling’s most significant works, and perhaps the most important example of post-modern architecture in England. It is also an example of the City planners’ late C20 ambitions to put up buildings that engaged with the public. Now is the time to re-appraise this monumental building, and we urge Historic England to give it the recognition it deserves by recommending listing at Grade II*.

Henrietta Billings

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.