This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

A living and shopping complex that showed the promise of high-tech in the 1980s

In recent years a slow trickle of listings has recognised the exceptional high-tech factories, office buildings and private houses built in the late 1960s, 70s and 80s where new structures or material technologies were developed for the specific project. But less glamorous high-tech projects, such as speculative housing, sports centres, schools and supermarkets, have also borrowed features and concepts from other building types or the world beyond architecture.

The Sainsbury’s superstore in Camden (1988) is clearly part of the Grimshaw family, using the practice’s signature industrial aesthetic and engineering focus to set itself apart from the other 19 superstores opened by the chain that year. Sir Nicholas Grimshaw and his team, led here by Neven Sidor, adapted existing technologies to satisfy the local authority’s insistence on a modern, innovative design. By 1985 Camden’s planning team led by Bill Risebero had turned down seven designs for the site. Sainsbury’s eventually gave in, and sought a new architect.

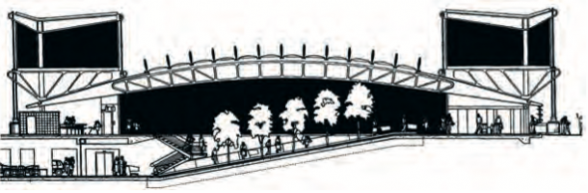

Grimshaw were highly-regarded designers of factories and offices, including the Herman Miller factory in Bath (1976) and the Financial Times printworks in London’s Docklands (1988). Camden were enthusiastic about the appointment, and with Sainsbury’s design guide at hand, Grimshaw’s team were largely left to their own devices. The resulting building is Grimshaw through-and-through: aluminium cladding, a wide-spanning column- free roof, exposed tensioning rods, relatively low construction costs, and porthole windows on the escape stairs. The roof uses shallow-curved metal beams to span the entire shop floor, taking a well-known concept and using it in a new setting. The architects also left the structure visible by taking a fire-proof coating originally developed for nuclear waste containers and applying it to the steel members, avoiding bulky insulation and cladding (although, unfortunately, Sainsbury’s still put in their standard suspended ceiling).

Characteristic touches are visible elsewhere: the workshop building on Kentish Town Road uses a reconfigurable cladding system similar to the one developed for Herman Miller’s distribution building in Chippenham (1982). The terraced houses facing the canal feature bus windows and factory unit loading-bay doors, the latter creating a retractable glass wall in the double-height living room. The houses didn’t just look good, they also worked hard to make a difficult site into a comfortable place to live at a competitive price. Martin Pawley in the Guardianwrote that the houses ‘may represent the beginning of a watershed in English domestic architecture’.

Space-age living didn’t take off as Pawley had hoped, but the project is still something rare and special. As well as creating a supermarket that looked like no other, the team managed to fit an unprecedented range of uses into the site without changing the scale of this complex urban setting. Grimshaw even convinced the Royal Fine Art Commission that the facade components on the supermarket reflected the Georgian terraced houses opposite on Camden Road.

We have submitted the whole complex for listing following an application for partial demolition and substantial alteration to Grand Union House and 16 Kentish Town Road, the workshop and nursery school blocks forming one elevation of the triangular site. In 2017 we were disappointed when the UOP Fragrances factory in Tadworth (Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, 1972-73) using the previously developed Zip-Up concept, was turned down for listing for not showing a ‘sufficiently high level of innovation in its materials, technology and constructional form’. Here we are hopeful that the role of borrowed technology in high-tech architecture will be recognised, as the Sainsbury’s complex reflects the possibilities of adapting industrial materials and methods to elevate everyday architecture into something extraordinary.

Grace Etherington

Credit: Grimshaw Architects

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.