This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

James Salmon established an architectural practice in Glasgow in 1830, which continued for two further generations. James Gillespie joined in 1898 creating Salmon, Son & Gillespie when William Kidd also joined as an apprentice. The younger Salmon and Gillespie continued until parting company in 1913. Gillespie then entered into partnership with Kidd. In 1914 Jack Coia, aged 16, joined Gillespie & Kidd, left for London in 1923 only to return at Kidd’s request following Gillespie’s death in 1927. Kidd himself died in 1928. Coia thus inherited the practice by then known as Gillespie, Kidd & Coia; the practice subsequently joined by Isi Metzstein in 1945 and Andy MacMillan in 1954. Design control of the this now atelier like practice was passed from Coia to Metzstein and Macmillan in 1955. The practice closed in 1986.

The revived post-war practice enjoyed Jack Coia’s legacy of the continued patronage of the Catholic Church for whom they designed a further 17 churches in Scotland. Secular commissions reflected the burgeoning rise and gradual decline of the Welfare State. Their commissions included housing, hospitals and education buildings mostly built in suburban settings in Glasgow and the Scottish New Towns. This range of building types offered unique circumstances and opportunities in which sacred design informed the secular design.

The overarching theme within the practice was that of a serious concern for a building’s context, the fullest consideration of all aspects of a site invariably informing the nature and arrangement of the building programme. This can be seen in Robinson College, Cambridge (1974-80) and at St. Peter’s College, Cardross (1958-66) where the surrounding landscape was preserved as an integral part of each composition.

However, five identifiable themes can be discerned in the work of the practice from the period of 1955-80; deep plan forms; structural integration; sectional articulation; expressive fenestration and perimeter planning. These themes emerged under the design control of Metzstein and Macmillan and were developed as a conscious reaction to many aspects of contemporary architecture and with a view to augment and enrich the language of modern architecture. Each theme is always integral to one or more of the others.

A preference for deep, almost square top lit plan forms emerged early; importantly in the design of St Paul’s, Glenrothes (1956), its wedge shaped plan opening towards a broad sanctuary and top lit altar anticipating the liturgical changes to come with Vatican II. At a larger scale the deep plan was followed through in the designs for St Patrick’s, Kilsyth (1961-65) and most monumentally at St Bride’s, East Kilbride (1963-65). Similar themes were explored under the sloped roof profiles of Our Lady of Good Counsel, Dennistoun (1964-66) and St Benedict’s, Drumchapel (1964-69), demolished in 1991 just days before it was due to be listed. Comparable opportunities in the exploration of deep plan forms were subsequently developed in the secular work in particular the education buildings such as St Peter’s College, Cardross (1958-66), Cumbernauld Technical College (1973-75) and Robinson College , Cam bridge (1974-80).

Structural integration refers to the use of load bearing construction and bespoke re-inforced concrete or steel framing. The particular structural system was selected on the basis that if no frame is needed then none should be used.

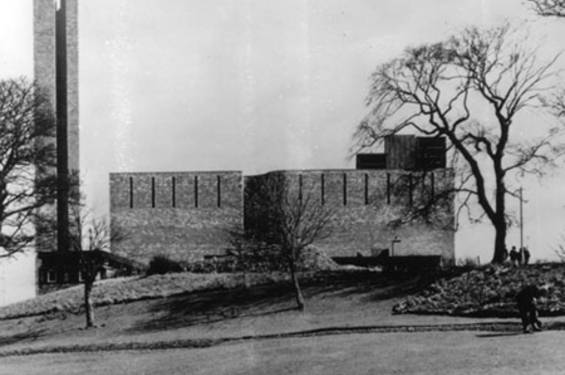

The load bearing structures expressively explore the mass, thickness and a variety of buttressing systems associated with brickwork. Exposed brickwork walls were variously patterned, their surfaces structured with either random bonding, horizontal banding or corbelling. This is most powerfully evident at St Bride’s, East Kilbride, St. Patrick’s, Kilsyth or the Lawns student residences at the University of Hull (1963-67). In some instances they were painted as in St. Paul ’s, Glenrothes, or rendered as at Wadham College, Oxford (1971) or alternatively, heavily roughcast as at St Peter’s, Cardross. In Wadham College Library, Oxford (1977) specially coloured, shuttered concrete was used.

The reinforced concrete structure designed for the four storey teaching wing of Simshill School, Glasgow (1956-63), was the first building by GKC to exhibit the use of off-façade columns, cantilevering and inverted floors. The framing is thus deeply embedded not only in plan but also in section, in a symmetrical structural arrangement which simultaneously facilitated the controlled admission of daylight, the volumetric scaling of the classrooms and circulation, the varied subdivision of floor plates, their readily accessible servicing arrangements, as well as the aesthetic continuity of the façade. This arrangement of a single corridor was explored to dramatic effect in the deeper twin corridors of Cumbernauld Technical College and the galleried circulation pattern of St. Peter’s Cardross. Framed structures were used only when necessary in order to elevate, often repetitive accommodation above the ground plane. This enabled the creation of larger spaces below, perhaps the most eloquent instance of this concept being the chapel and refectory at St. Peter’s.

Sectional articulation concerns the buildings having a base, a middle and a top whilst in addition, creating an proportionate variety of rooms and the accommodation of a complex programme of large volumes and smaller, often repetitive, cellular spaces within a single integrated whole.

This is clearly evident in the stepped sections of Cumbernauld Technical College, St. Peter’s Cardross and Robinson College, Cambridge. In each case an extraordinary variety of very large, or large groupings, of spaces are integrated below the continuous soffits of the concrete superstructure. The articulation also deals with the experience of buildings from a distance, their silhouette and large scale modelling. On approaching them they appear to adjust their scale so that when at close quarters the experience is intimate and of human scale. From inside, the stepped section, either roof or balcony, lessens the sense of being on a precipitous face of a multi-storied building.

Similar concerns are evident in the churches. The ascending scale of the presbyteries, churches and towers of both St. Paul’s, Glenrothes and St. Bride’s, East Kilbride have a similar effect. They both provide foreground and background buildings. From a distance the towers of both buildings clearly signal their religious status and, in moving toward them, the perception and profile of both buildings progressively changes, the lower buildings guiding to an unequivocal, and in the case of St. Bride’s a monumental statement of entry. In both cases this experience is reinforced by the detailing of it becoming more refined when those parts of the buildings can be seen close to, or can actually be touched.

The theme of expressive fenestration concerns the day lighting of buildings through separately scaled and subdivided openings which modulate light in ways which are qualitative as opposed to quantitative. Patterns of fenestration deliberately varied in size, shape, depth, visibility and location according to both purpose and effect. Consequently light is manipulated to provide graduated variations in the intensity of light experienced within buildings. This corresponds to the spatial hierarchy within the buildings.

Openings can take the form of large groupings of windows to form continuous screens or high level clerestories often with randomly spaced mullions. Such systems are combined with contrasting hole-in-wall openings. Common to the churches was the use of concealed light sources such as in St. Paul’s, Glenrothes, Our Lady of Good Counsel, Dennistoun or most extraordinarily in St Bride’s, East Kilbride. Here, within an apparently windowless brick interior there are no fewer than six concealed light sources. Simshill School exhibits the use and set back bands of high level clerestory windows over light shelves, which reflect light into the rear of the classrooms, giving scale to the otherwise high edge of the room. The overlapping levels of the light diffusing, shallow vaulted, white ceilings of St Peter’s, Cardross allows light to enter the chapel nave and refectory via the visually concealed, clerestory windows.

Perimeter planning refers to the linear arrangements of large scale, multi-cellular buildings; in effect inhabited walls which clearly differentiate between, and define different spatial domains, public and private. The echeloned walls and enclosed entry courts of the student residences at the University of Hull clearly embrace the great lawn separating pedestrians from traffic, its angular, three storey inner wall, deeply holed with private balconies faces the single space of the expansive lawn whilst the stepped geometry of the outer walls is single storey with occasional two storey accents. A simple ninety degree rotation of the internal half landings induces the level changes that allow the building to effortlessly traverse the gently undulating topography, whilst the plan allows the preservation of all the mature trees.

A similar concept applies in Robinson College, Cambridge albeit with a far more complex programme. Two continuous, linear walls of accommodation, one nesting in the other, are arranged either side of a sequence of four courts, the whole folded into the perimeter of a suburban block. The larger scaled inner wall facing the garden is highly ordered, its super-structure consisting of levels of student rooms. With the exception of the entry tower, the outer wall is lower and more varied in scale with an ad hoc series of architectural features, all of which tailors the large scale of the college to that of the street. In following the footprints of the villas which formerly occupied the site the College inherited a mature garden landscape with minimal loss.

In both buildings external space is ordered and arranged to create legible though complex spatial sequences in accord with the buildings’ respective programmatic dispositions.

In conclusion there can be little doubt that the architecture of Gillespie, Kidd & Coia can be considered to be of international standing. The thematic nature of their work targeted universal architectural themes whilst the imaginative, artistic rigour which underpins the buildings imbues them with distinctive integrity and a intellectually robust aesthetic. Their significance has so far received little or no mention in the annals of architectural histories and with some buildings already destroyed and others endangered they may soon pass into the realms of mythology.

Further reading

Mark Baines is a tutor and lecturer at the Mackintosh School of Architecture, Glasgow School of Art. Between 1976 and 79 he worked at GKC. He is to curate a new exhibition of GKC’s work to take place at the Lighthouse in Glasgow in late 2006.

Mark Baines

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.