This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

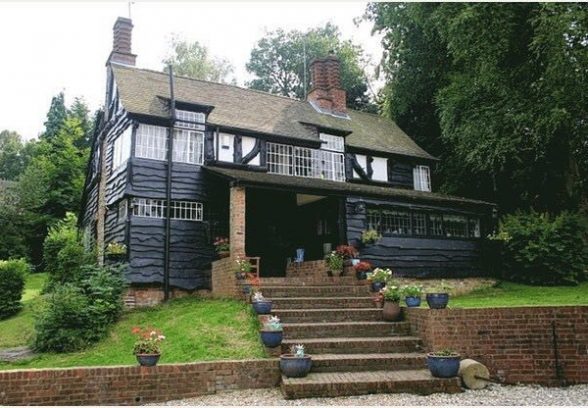

Photo: Nathan Fraser

No building that has crossed my desk in my first three months as Conservation Adviser has captured my eye in quite the same way as a house by the remarkable Irish architect Ernest Trobridge; Swedenborgian, militant vegetarian and architectural visionary. He settled in London where his earliest known work was the remodelling of the Camden Road New Church in 1908. He built little before the war, but his 1913 housing in Golders Green foretold both a socialist impulse and a technical ability to unite a highly rational configuration of internal space with an idiosyncratic composition of architectural features. These threads were to run through his life’s work.

It was with the discovery of elm wood as a building material that this philosophy came into its own. Faced with a severe lack of affordable building materials post-war, Trobridge looked to tradition out of necessity rather than whimsy, and discovered that, while unseasoned elm was difficult to work with due to its tendency to warp, it was pliable and could be cut in ways which allowed for shrinkage as the wood dried in situ.

A prototype was showcased at the 1920 Ideal Home Show as an affordable way of providing high quality mass housing. Half the price of brick builds, and with construction times of eight weeks or less, elm houses required no scaffolding or foundations, and could be erected on site by non-specialist labour. The standardised framework allowed for a wide degree of flexibility: every house Trobridge designed with this system was unique. Trobridge’s ideas were never widely adopted by government, but this marked a turning point in his career. He would work for most of his life with smaller developers and individual clients.

At Roffes Lane in Chaldon, Surrey are some of the first examples of his patented system. These houses were built in 1920, a year before Slough Lane in Kingsbury – probably the best known example of his earlier work. Originally a group of three, today there are just two, with the future of 18 Roffes Lane uncertain. After we strongly objected to demolition, permission was refused, but we fear that this decision could be overturned on appeal and have put it forward for listing.

As with many of Trobridge’s early houses, 18 Roffes Lane appears as a romantic take on the Wealden-type vernacular; subtly asymmetrical with leaded light windows running unevenly across the façade, and bold brick chimneys. Seemingly traditional, it is in essence a thoroughly modern building. With its lack of foundations, it was essentially raised on columns; the elm allowed for a free façade where windows and doors could be arranged at will. Trobridge also had a particular fondness for ribbon windows, wrapping around corners. These of course are all fundamental principles of the ‘new architecture’ articulated by Le Corbusier some years later. Originally the roof would have been thatched, with a built-in fire sprinkler system – truly a machine for living in. His ability to look to the past and also embrace the modern is at the heart of his work.

A second domestic building from the same period, Prinsted Grange by Oliver Hill, shows a different sort of contradiction. As a good example of Hill’s early foray into Arts & Crafts (1923) it shares Roffes Lane’s irregular arrangement of windows and use of natural materials: brick and thatch with reclaimed timber throughout. In spirit, however, it is a relatively straightforward essay in revivalism, standing in contrast to the synthesis of Trobridge, and also to Hill’s own work of the thirties and beyond which falls, ostensibly at least, in the modern idiom, such as the elegant, curved and concrete Midland Hotel of ten years later. Here there is no hint of what was to come in his country houses of the 1920s. His later ability to embrace modernism makes the quiet picturesque nature of this earlier work all the more remarkable. It demonstrates not only his complex relationship with the modernist project, but also the diversity to be found in the small country house design of the 1920s.

Tess Pinto

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.