This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Image: Joris Vanbillemont

See it, Say it, Save it!

London’s historic Liverpool Street Station and the former Great Eastern Hotel (now Andaz Hotel) – Grade II and II* Listed buildings respectively – are threatened with destructive new plans by developers Sellar Property and Network Rail, that would see the ornate concourse roof and several key twentieth century heritage buildings demolished, to be replaced by two overbearing new office blocks of 10 and 15 storeys.

C20 has strongly objected to the plans and joined an unprecedented coalition of heritage organisations to oppose the development – including SAVE Britain’s Heritage, Historic Buildings and Places, The Georgian Group, The Spitalfields Trust, Civic Voice, London Historians and The Victorian Society. The national body, Historic England, has also come out forcefully against the proposals.

Sign the petition now and send a message to Sellar and Network Rail that these damaging proposals must be scrapped, and that developers greed cannot trump commuter need.

Images: Sellar Properties

All change

The Society has serious concerns that the commercial office development, designed by architects Herzog & de Meuron, would result in an unacceptable level of heritage loss and have a hugely detrimental effect on the setting of the station and hotel. A sizeable area of the 1985-91 train shed roof – recently included within the station’s revised Grade II listing and praised by Historic England as ‘enhancing the spatial quality and cohesiveness of the remodelled station’s unified concourse’- would be demolished. As would the elegant brick entrances and clocktowers on Bishopsgate and Liverpool Street, which were excluded from the revised listing – a decision the Society has questioned.

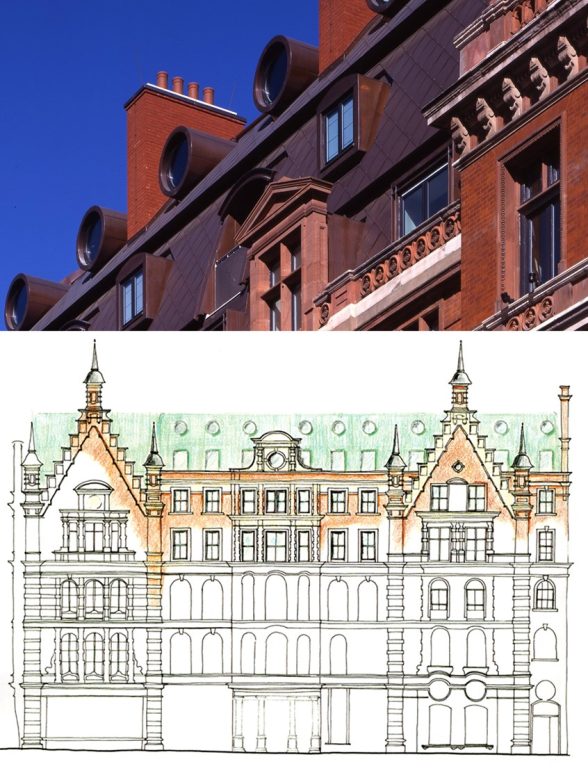

The 1990s refurbishment of the former Great Eastern Hotel was carried out by leading architects and designers and executed to the highest standards. These additions are also included within the updated and upgraded Grade II* listing of the hotel, yet are currently being overlooked by the developers and dismissed as ‘modern’ and therefore of little to no value. The proposals would remove the hotel’s mansard roof, insert huge pilings into the atrium space and completely strip the interiors back to their 19th-century form.

Image: Tim Brown

A campaign revived

British Rail first sought to redevelop the 19th-century Liverpool Street station in the mid 1970’s. A vociferous and successful heritage campaign – the Liverpool Street Station Campaign (LISSCA) – figure-headed by lawyer George Allan and involving the poet John Betjeman thwarted British Rail’s demolition plans and led to the Grade II listing of the Liverpool Street offices and western train shed in 1975.

In a 1975 interview, Betjeman said: “Old stations are places of great joy because of greetings, and great sadness because of partings. They are part of the lives of a nation.” Liverpool Street station even featured in one of Betjeman’s poems, A Mind’s Journey to Diss. It began: “Dear Mary, Yes, it will be bliss / To go with you by train to Diss / Your walking shoes upon your feet / We’ll meet, my sweet, at Liverpool Street.”

At the urging of the Greater London Council, British Rail then came forward with a new scheme which saw a greater degree of retention, extension and upgrading of the Victorian station. This was a significant cultural realignment which was both emblematic of a changing attitude to historic architecture and city planning, and encouraged future campaigns which in themselves made a decisive difference to how Victorian architecture, and in particular Victorian railway architecture was perceived and valued.

Image: Tim Brown

A milestone in the heritage conservation movement.

The radically revised scheme was carried out between 1985 and 1991 by British Rail’s Architecture and Design Group, directed by Nick Derbyshire, working with the project architect Alistair Lansley. The work involved extending the Victorian western train shed further west with a second transept over a new concourse, containing shops on elevated walkways at its southern end, rebuilding an office at 50 Liverpool St and creating two new southern entrances on Liverpool St and Bishopsgate.

The 1985-91 work was sensitively handled and executed to the highest standards. New additions borrowed from the design of the Victorian station and sought to enhance what remained of it. The architects took a conservation-led approach, which was applauded by contemporary architectural critics:

50 Liverpool Street was rebuilt “in [a] full-blooded Victorian style” (Building Design, 1992); new entrances were “distinguished”, “echoing the architecture of the adjoining Great Eastern Hotel” (Architects’ Journal, 1988); and roof trusses to the extension carefully replicated those on the 19th-century train shed. The new work showcased intelligent design and careful attention to detail in response to a demanding site and brief. The late 20th-century work was hailed as a milestone in the heritage conservation movement, it’s an important part of the history and development of Liverpool Street and its architecture is of a very high standard.

Images: Manser Practice

Former Great Eastern Hotel

The Great Eastern Hotel was completed in 1884 and an extension added from 1889-1901. In 1995, the hotel was acquired by new owners, the Arcadian International Hotel Group (later taken over by Wyndham International) and Conran Group. A design team was appointed, headed by Manser Associates (led by Jonathan Manser) with the Conran Design Partnership acting as designers for the interiors. Alan Baxters provided structural engineering and conservation advice for the project.

Manser and Conran undertook an extremely extensive remodelling of the hotel, which had been much neglected. They restored and refurbished the hotel’s interiors, and considerably expanded its overall envelope, between 1997 and 2000. Key interventions included:

Images: Manser Practice

C20 Caseworker Coco Whittaker commented:

‘While many may think of Liverpool Street Station and the Great Eastern Hotel as belonging exclusively to the 19th century, both were extensively remodelled in the last decades of the 20th century. The successful campaign to save the station and the sensitive, high-quality architectural interventions of the 1980s and 90s that followed were hailed as a milestone in the heritage conservation movement, yet are now threatened with demolition barely 30 years later. We’ve joined the LISSCA campaign to make the case for the quality and value of the late 20th-century work, and to fight the devastating plans that would permanently disfigure this iconic gateway to London.’

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.