This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Image: Hopkins Architects

C20 is celebrating the listing of another highly significant early 1990s building, with the former Inland Revenue Centre in Nottingham by Hopkins Architects (1993-95) – the first British project to receive maximum points under the BREEAM assessment – awarded Grade II listed status, just as the building reaches its 30th birthday. News of the listing has added poignancy, as this was a case particularly championed by Elain Harwood – the C20 stalwart and Historic England investigator, who was born in Nottingham and sadly died in March of this year.

The Inland Revenue (now known as HMRC) vacated their purpose-built complex in 2022, relocating to new offices elsewhere in the city. Outline planning permission for conversion from office to residential use was first granted in February 2018, with proposals for 332 one and two bedroom dwellings. After consultation with Hopkins Architects, the Society concluded that the building would be suitable for conversion, but that there was a risk of serious damage to the clarity and fabric of the original design, without a sympathetic approach and the protection afforded by listing.

With the support of C20 Society, Nottingham Civic Society applied to list the building in July 2021. Later that year the site was acquired by Nottingham University, having been on the market for £36 million. The University has outlined proposals to convert it to a campus for their final year and post-graduate students. C20 looks forward to working closely and constructively with all parties as their plans develop.

Image: Hopkins Architects

History

In 1989, Inland Revenue announced its decision to relocate almost 2,000 posts from London to Nottingham, partly in response to the rising cost of office space in London. Locals and heritage bodies successfully prevented a design-and-build package for a new Inland Revenue Centre from going ahead, on the grounds that it was of poor design quality and would have a detrimental impact on the setting of the nearby Nottingham Castle. This led to an open architectural competition being launched in 1992, with the architects Michael Hopkins & Partners emerging as winners. This Inland Revenue Centre was built in 1993-94 by Hopkins, working with Ove Arup & Partners.

Design

The centre is located at Castle Meadow; a key site between the canal to the north and the railway to the south, with Nottingham Castle positioned on a steep bank above. Hopkins divided the Inland Revenue Centre into seven 3 and 4 storey blocks, to create a whole new urban quarter: 6 offices and a centrally placed amenity building, with a distinctive fabric roof suspended from four, raking steel masts. This was the visual and social centre of the complex, containing a ground floor sports hall with a bar and restaurants above. Separating the complex into individual blocks had practical benefits for estate management, but it also helped Hopkins to establish a “civilised urban pattern” (Architectural Review, 1995) of human-scaled buildings and intimate spaces that would appeal to employees.

Blocks are arranged along a central curved boulevard, with bands of radiating streets extending perpendicular to it and affording clear views of the castle. Its plan is quite traditional and in keeping with the historic character of Nottingham city, featuring enclosed landscaped courts, tree-lined streets and buildings that overlook ‘private’ gardens.

Image: RIBA

Green Project

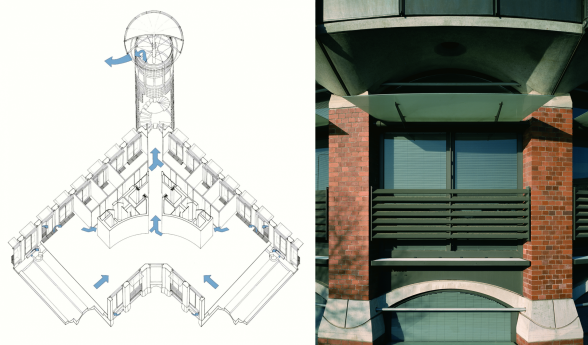

The complex was a pioneering sustainable building, being the first British project to receive maximum (21) credits under the BREEAM environmental assessment, which was established in 1988. This was a requirement of the clients and was fully embraced by the architects. When the centre was built, modern offices tended to have particularly high energy consumption, using air-conditioning to deal with the excessive heat generated from lighting, equipment and solar gain. The Inland Revenue Centre departed from this trend and, by encouraging lots of daylight and natural ventilation, created a much more environmentally friendly building.

External shading was provided by horizontal, projecting, glass ‘light shelves’ at door-head height, which reflect daylight up onto the ceiling, and by the deep reveals of the brick piers. Windows are triple-glazed, with a venetian blind in the outer cavity. The office buildings utilised local bricks for load-bearing piers, which alternate with full-height glazing. The tapering piers support barrel-vaulted concrete floors, which span the width of each building and provide thermal mass to help regulate the internal temperature. Glass block stair towers at the corners form part of the ventilation system, expelling hot air around the edges of the fabric covered roofs, which can be hydraulically-lifted if necessary. The buildings are capped with projecting lead-clad attics.

A computer system known as a building energy management system (BEMS) was used to control air flow, temperatures and light levels and optimise energy efficiency. Such controls could, however, be overridden by the occupants if they wished. The design of the Inland Revenue offices was truly integrated and sophisticated. As the Architects’ Journal observed in 1995, “The prevailing green orthodoxy now demands a reinterpretation of traditional attitudes to lighting and ventilation and Hopkins, by allowing the structure to assist as an integral component in the prosecution of these aims, has significantly advanced office building typology”.

Image: Hopkins Architects

Mike Taylor, Principal, Hopkins Architects:

“Our Castle Meadow project for the Inland Revenue was forward thinking both in using low energy environmental systems, and in the way they were expressed as an integrated part of the overall architectural language. The main buildings were very well detailed and robustly built out of durable prefabricated components and as a consequence are in excellent condition today. We were delighted when the University of Nottingham purchased the entire site thereby securing its future for the wider public benefit in such an important location within the City centre. Over time the individual blocks can be modified for academic use, which is relatively straightforward and a good example of the long life loose fit philosophy we should all be building to. Now that 30 years have elapsed since construction began it was expected that the site would be Grade II listed, which should further secure its legacy as an important milestone in the UK’s architectural history.”

Coco Whittaker, Senior Casework, C20 Society:

“We’re thrilled that the remarkable Inland Revenue Centre has been listed. It is an exceptional collection of buildings and spaces, pioneering in its design and green ambitions. The Inland Revenue Centre is the sixth Hopkins building to be included on the National Heritage List for England and follows the listing of 22 Shad Thames in London in summer 2021 – it’s fantastic that the practice’s work and contribution to 20th-century architecture in England is being recognised in this way. It was a major 1990s public commission and is the practice’s youngest building to be listed. We hope now that the listing will inform any proposed interventions to adapt the site for use by the university. We look forward to seeing these buildings in use once again, at the centre of student life in Nottingham.”

Hilary Silvester, Nottingham Civic Society:

“We were extremely worried about the building originally proposed for this site [in the early 1990s] and the impact it would have on views of Nottingham Castle, hence we wholeheartedly joined in the call for a design competition. As well as being a most attractive building, which should have a good future with its new owners, the University of Nottingham, the [Hopkins] building has been praised for its sustainability, a concept dear to the hearts of Nottingham City Council and one which the original architects embraced thirty years ago.”

Image: Hopkins Architects

Hopkins Architects

Hopkins Architects is a leading architectural practice, established by Michael Hopkins (b.1935) and his wife Patricia (née Wainwright, b.1942) in 1976 (as ‘Michael Hopkins Architects’). Michael has been awarded a CBE and Knighted for Services to Architecture, and he and Patricia won the RIBA Gold Medal for Architecture in 1994.

The project team for the Inland Revenue Centre included Michael Hopkins, Ian Sharrav, William Taylor and Peter Romaniuk. The practice was particularly prolific around this time, and after their breakthrough Schlumberger Research Centre (1985), key commissions followed such as the Mound Stand at Lords Cricket Ground (1987) and a new opera house at Glyndebourne (1994). The quality and versatility of their work is demonstrated by the approaches taken on each project, giving thought to local context, materials and tradition. At its best, their architecture combines the engineering elan of high-tech, with a particularly English sensibility.

The former Inland Revenue Centre becomes the sixth building by the practice to be recognised with national listing:

Image: Hopkins Architects

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.