This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

London: The Cenotaph

Status: Listed Grade I

Architect: Sir Edwin Lutyens, 1920

Perhaps it is rather English that the national memorial to the million British Empire dead should not be one of the grand projects for triumphal arches and avenues proposed during the war but what was originally intended to be a temporary structure, of wood and plaster, translated into Portland stone. In 1919, the Prime Minister needed to find “some prominent artist” to design a temporary non-denominational “catafalque” for the Peace Celebrations planned for 19th July. Sir Edwin Lutyens was recommended by Sir Alfred Mond, First Commissioner of Works, and he is said to have told Lloyd George, “not a catafalque but a Cenotaph”, that is, a monument to someone buried elsewhere. There are many legends attached to the design, which Lutyens is said to have sketched out in a matter of minutes, but he had already designed a more elaborate Cenotaph for Southampton. The tall pylon carrying the symbolic sarcophagus was composed with immense subtlety and refinement. All vertical and horizontal surfaces are modelled with curved entasis or optical corrections, and the monument is given dynamism by Lutyens’ characteristic method of alternating set-backs.

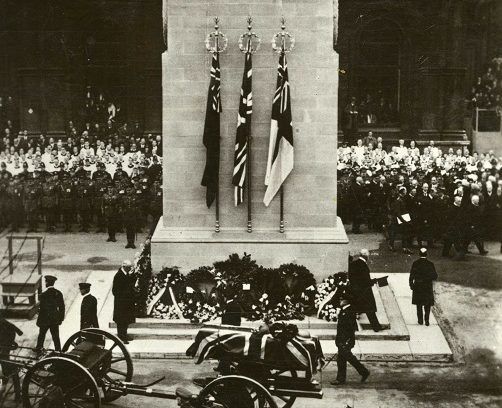

The temporary Cenotaph was an outstanding success in that, after the generals, soldiers and politicians had marched past, it became a focus for grief, “the people’s shrine”. A million people made pilgrimage and a mountain of flowers and wreaths were piled up around it. Demands arose for the temporary Cenotaph to be re-created in stone and eventually the government acceded to what Lutyens called “the human sentiment of millions”. Small changes were made to the design, although Lutyens was not permitted to have the flanking flags executed in painted stone so that they would remain still. The permanent Cenotaph was unveiled on Armistice Day, 1920, when the body of the Unknown Warrior was drawn past to be interred in Westminster Abbey. Lutyens’ design was criticised by some for its complete lack of Christian symbolism, but – as with his work for the Imperial War Graves Commission – he wanted forms which had meaning “irrespective of creed or caste” as he knew well that it was not just Christians who had been fed into the slaughter. That did not deter the Catholic Herald from dismissing the Cenotaph as “nothing more or less than a pagan monument, insulting to Christianity… a disgrace in a so called Christian land” as it was for “Atheist, Mohammedan, Buddhist, Jew, men of any religion or none”. Lutyens later recounted how “There was some horror in Church circles. What! A pagan monument in the midst of Whitehall! That is why we have a rival shrine in the Abbey, the Unknown Warrior, but even an unknown soldier might not have been a Christian, the more unknown the less sure you could be.”

So perfect was the Cenotaph found to be for its melancholy purpose that, after another war, nothing more was needed than to carve two more dates into the stone: “1939-1945”. Lutyens died during that war. His daughter Mary later recalled passing the Cenotaph immediately afterwards and how “The aloof, lonely perfection of its beauty pierced me… I can never pass it now without feeling he is there – it is his soul, the quintessence of his genius – as much a memorial to him as to the dead of two wars – but above all a triumphant affirmation of the spirit of harmony which makes order out of the chaos of materialism. Perfect order is perfect well-being”.

Gavin Stamp

Either enter the name of a place or memorial or choose from the drop down list. The list groups memorials in London and then by country

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.