This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Image: Jonathan Taylor

Congratulations to Bradford! The West Yorkshire city has just been crowned the next UK City of Culture for 2025, beating off rival bids from Wrexham, Southampton and County Durham.

While it may be best known for a wealth of Victorian civic architecture and industrial heritage – the legacy of being a regional textile powerhouse in the late 18th and 19th centuries – Bradford also boasts a number of highly distinctive and unusual 20th + 21st century buildings. Here we highlight some key examples of its modern architectural heritage, from singing bus stops to ‘severed head robot’ brutalism, a Japanese inspired sports centre to an International Modernist style department store.

C20 Director Catherine Croft will also be appearing at the Bradford Literary Festival on July 2nd, debating the city’s heritage in ‘Planning Bradford :Changing Times, Changing Architecture’. Tickets are available to book here

Image: Tim Ronalds Architects

Bradford Odeon – William Illingworth (1930)

Bradford came within a whisker of losing its 92-year-old Odeon building. The city centre landmark was earmarked for demolition for several years to make way for a largely unwanted office scheme. Fortunately, as the economic downturn bit, the replacement scheme became financially unviable and was eventually scrapped in late 2012. The ex-cinema eventually transferred to the council for just £1 and after a protracted period of uncertainty, the NEC group took over the site and a conversion to a new 3,800 seat live music and entertainment venue known as ‘Bradford Live’ is now underway. Backed by a £4m DCMS (Department for Culture, Media and Sport) grant through the Northern Cultural Regeneration Fund (NCRF), its scheduled to open in 2024.

Designed by William Illingworth, the chunky Italian Renaissance-style building was the first cinema in Britain to be purpose-built for ‘talkies’ and, although it was altered considerably internally before closing in 2000, it has proved remarkably resilient. Urban explorers later discovered that some of its original Art Deco features and ceilings remain intact and hidden from view, these will be be preserved in a state of ‘arrested decay’ in the new Bradford Live venue, due to open in 2024-25 as world-class leisure, entertainment and business destination.

Image: West Yorkshire Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Sunwin House – WA Johnson / CWS(1935-36)

Designed by WA Johnson of CWS for the City of Bradford Co-operative Society in 1936, the store was built in the International Modernist style and heavily influenced by the German architect Erich Mendelsohn, particularly his designs for the Schocken Department store in Stuttgart (1928). This was an early and influential example of the open store principle, with lifts and stairs tucked around the edges of the shopping area and it also had the first escalators to be installed anywhere in a Co-op store.

Its unaltered appearance, both externally and internally, is extremely rare and the building was Grade II listed in 2006. Latterly occupied by the retailer TJ Hughes, it closed as a retail premises in 2011 and has been empty ever since. In 2019 the Architectural Heritage Fund (AHF) awarded a project viability grant to Freedom Studios Ltd, a contemporary theatre company, to investigate its potential as a multi-use cultural space.

Image: Jonathan Taylor

Arndale House – John Graham and Company (1963)

Designed by the North American firm, John Graham and Company, who also designed the Seattle Space Needle, Arndale House is believed to be the practices only UK project. The central area of Bradford was systematically rebuilt between 1955 and 1965, old factories, warehouses and office blocks were removed and the area re-planned as a shopping and commercial hub. Arndale House was just one of many American style shopping centres and offices built in northern industrial towns in the mid to late 20th century.

The nine-story office block is characterised by its regular pattern of single-paned and seemingly frameless windows and survives in good, relatively unaltered condition. The building is currently empty and proposals emerged in 2021 for a conversion to residential usage by by Xchange Development Company. While supportive of a conversion in principal, the plans to replace the windows between the second and eighth floor with three panelled double-glazed openable UPVC units were opposed by the Society, with a preference for a more sympathetic upgrading of the glazing to improve the thermal efficiency of the building. An application by C20 and Bradford Civic Society to have the building listed was also turned down by Historic England.

Image: Zoonar GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

Bradford Magistrates Court – Clifford Brown / City Architects Department (1969-72)

Designed by William Clifford Brown and opened June 1972 by the High Chancellor Lord Hailsham, Bradford Magistrates Court was originally joined on Centenary Square by the Central Police Station, a product of the same City Architects Department. The pair of buildings were long thought to be an obtrusive presence and impeded views of the Grade I listed gothic Town Hall, to the extent that Will Alsop’s visionary early masterplan of the early 2000’s would have seen both buildings demolished to make way for a new city park.

Ultimately the masterplan was watered down and while a new 3,600 metre square civic square was opened in 2012, with a mirror reflection pool and the UK’s highest fountain, only the less significant Police Station made way for the development. The remaining Magistrates Court is a dignified and restrained example of civic brutalism, a low-slung square with boxed out windows on a raised podium, dressed in Bolton Woods sandstone quality. It has an understated formality which, despite the early criticism, well suits its position next to the City Hall and a main Civic Square.

Inside is also the artwork Gordian Knot (1972) by noted Yorkshire sculptor Austin Wright. Made from aluminium and standing over 6 feet tall its title symbolises the function of lawyers in solving disputes and cutting through legal problems.

Image: Rob Ford / Alamy Stock Photo

Highpoint – John Brunton & Partners (1972)

Perhaps the most controversial brutalist building in Bradford, Highpoint was built in 1972 for the Yorkshire Building Society and was considered to be a ‘beacon of modernity’ in the mostly Victorian city centre. Pevsner witheringly described it as “An aggressive missile-silo-like office tower”, while Owen Hatherley, perhaps admiringly, thought it “utterly freakish, the severed head of some Japanese giant robot clad in a West Riding stone aggregate, glaring out at the city through blood red windows, the strangest urban artifact in a city which does not lack for architectural interest”. In the foyer of the building, a William Mitchell mural entitled ‘Bradford Old and New’ showcased notable local landmarks including City Hall, the Wool Exchange and The Alhambra.

Bradford Civic Society have spiritedly campaigned for the building to be recognised for its contribution to the city’s postwar heritage. They hosted a ‘Save High Point / Raze High Point’ debate in 2018, with C20 Director Catherine Croft and Sir Simon Jenkins on opposing sides, with the audience ultimately agreeing it should be saved. After standing empty for over 25 years, an £11 million scheme convert the tower to residential apartments finally began in 2o21, and is due to open in 2024.

Image: Jonathan Taylor

Richard Dunn Sports Centre – Trevor Skempton / Bradford City Architects Department (1974-78)

This structurally pioneering Leisure Centre – inspired by the work of Kenzo Tange and Frei Otto – was designed by Trevor Skempton in the mid 1970s and was reputedly one of the first buildings in the country to make use of Computer Aided Design. Named in honour of hometown hero Richard Dunn, the local scaffolder turned boxer who fought Muhammad Ali for the heavyweight championship of the world, this tented ‘big top’ has been a landmark on the city skyline for over 40 years.

The centre closed permanently in 2019 after the leisure facilities were relocated to a new sports centre nearby, leaving the building threatened with imminent demolition until a last-ditch application by C20 Society saw the building Grade II listed. Discussions are now ongoing about the future of the site, with C20 currently developing alternate for proposals for how this Bradford icon could be re-imagined.

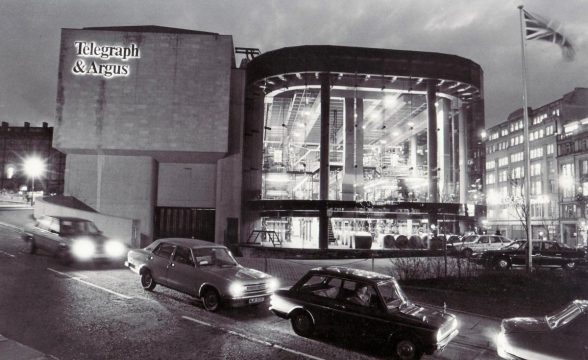

Image: Telegraph and Argus

Former Telegraph and Argus Print Hall – Robinson Partnership (1979-80)

Designed by the Robinson Partnership for the Telegraph and Argus newspaper, this sheer curtain of brown tinted glass with curved corners was intended to be opaque and screening the interior functions during the daytime, but dramatically transformed by night, dissolving into transparency to show the printing presses at work – as Pevsner described ‘ illuminated like a piece of street theatre’. In this regard, it bears comparison with the Financial Times Printworks in London’s Dockland by Grimshaw Architects (1988), which was Grade II* listed in 2016.

The Telegraph and Argus vacated the Hall Ings site in 2020. After a new external entranceway was installed to facilitate public access, it has recently been let to a hospitality business and it should soon be occupied by bustling diners, replacing the whirring of the printing press.

Image: Mick Flynn / Alamy Stock Photo

Bradford Law Courts – Napper, Collerton & Partners (1989-92)

Built on the site of the old Exchange Railway Station right in the heart of Bradford, the combined Law Courts contains eight crown courts and two county courtrooms, staff and visitor facilities. Built in a combination of local sandstone and lead clad stainless steel, it was the recipient of a Civic Trust award in 1993 for its successful response to the historic city centre.

While rather dismissively described by Pevsner in ‘The Buildings of England’ as “expensive-looking and facetiously detailed”, in ‘The Buildings of Criminal Law’ (2016) Historic England stated: “The exterior of the Combined Court Centre in Bradford, embraces current architectural thinking and often reference courts’ historical roots, such as by the use of columns evoking their classical predecessors.” Indeed, with its playful postmodern flourishes, high quality materials and build, this has endured as one of the best late Twentieth Century additions to the cities fine assortment of civic buildings.

Image: Bauman Lyons

Manchester Road ‘Musical’ Bus Stops – Bauman Lyons (2002)

As part of Bradford’s bid to become the 2008 European Capital of Culture (ultimately losing out to Liverpool), the city ran an architectural competition to design 6 landmark bus shelters for a new guided bus route along Manchester Road.

Competition winners Bauman Lyons Architects collaborated with sound installation artists to create a series of ‘musical’ interactive shelters, with more than a touch of Alexander Calder in their bold red finish and sculptural form. Heated seats were powered by mini wind turbines mounted on 12-metre masts, while colour-recognition cameras triggered music and words which changed according to people’s clothes, passing traffic and the arrival of a bus.

Image: Joel Chester Fildes

Lister and Velvet Mills redevelopment – David Morley Architects (2006)

Built in 1838, Lister Mills is a stunning complex of Grade II* Listed mills and warehouses, its 250ft high Italianate campanile chimney dominates the Bradford skyline. Once the largest silk factory in the world, a workers strike in 1890–91 was a key moment in the establishment of the modern Labour Party movement, yet by the 1980’s it was in terminal decline and finally closed in 1999.

Developer Urban Splash took over the semi-derelict site in 2000 and began restoring it for residential and commercial space. David Morley Architects and Pryce & Myers constructed a 100m long, two-storey line of residential modules on the rooftop. The swept arcs of curved plywood ribs were designed to mirror the twisting shape of a plaid of woven silk.

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.