This website uses cookies

This website uses cookies to enable it to function properly and to analyse how the website is used. Please click 'Close' to accept and continue using the website.

Image credit: Phil Sayer / C20 Society

Following an application by C20 Society, the remarkable Sphinx Hill house in Oxfordshire has been Grade II* listed by the Department of Culture, Media and Sport. Designed by John Outram Associates (JOA) and built in 1998-99, the designation makes the Egyptian style property the youngest listed building in Britain, and arrives just days before the architect, Outram, celebrated his 90th birthday.

Sphinx Hill was placed on the market for the first time in 2022, selling for £2.3 million in December of that year. This prompted C20 Society to submit a listing application for the property, to guard against the risk of unsympathetic alteration or demolition. It is exceedingly rare for a building under the age of 30 years old to be granted listed status, and the II* designation reflects its national significance – a ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ (or total artwork) of architecture, interior and landscape design.

Image credit: Phil Sayer / C20 Society

Egyptian revival in Britain

The house was commissioned in 1994 by a couple with a share interest in ancient Egyptian culture, and sits on a riverside plot located in the village of Moulsford, that provides dramatic views across the River Thames. The stretch of the river running through Oxfordshire is traditionally known as ‘The Isis’, after the Egyptian goddess.

Outram had noted that ‘none of the buildings along the river are totally serious’, with reference to the grand Victorian and Edwardian villas designed in the picturesque tradition, as well as the many playful boathouses and follies. Yet Sphinx Hill is a rare example of a late twentieth-century country house, utilising Post-Modern idioms and symbolism to revitalise an Egyptian ‘revivalist’ tradition in Britain that dates back to the early 19th century. Well-known Egyptian revival buildings include the Penzance ‘Egyptian House’ (1835-1836) and the Temple Works spinning mill in Leeds (1836-1840), both Grade I listed.

Relatively modest in size, the two storey, three-bedroom Sphinx Hill, is symmetrical in form, with barrel-vaulted roofs reminiscent of the funerary complex at Djoser in Saqqara, crowned by an attic storey resembling a giant eye of Horus. The exterior is a polychromatic composition in ‘mint chop chic’ render, featuring a winged solar disc over the main entrance, tartan pattern tiling along the base, and black column capitals topped with terracotta circles, representing the hieroglyph for the rising sun.

The centrepiece of the ground floor is a cross-vaulted dining room with pilasters and a floor of Egyptian limestone, to one side is a swimming pool wing, decorated with mosaic flooring and rich blue and gold columns. The theatrical main living room is on the first floor, to afford the best views of the river. Details include ox-blood red freestanding columns, topped with silvery palm capitals, an enigmatic open-face pyramidal fireplace, and bronze scarab doorknob throughout.

A formal garden connects Sphinx Hill to the Isis, with mirror-pools guarded by pairs of sphinxes and a cascading watercourse on the main axis of the house, representing the course of the Nile from its source in the mountains, to its delta at the sea.

Image credit: Phil Sayer / C20 Society

Post-Modernism

Post-Modernism was a movement and a style prevalent in architecture between 1975 and the late 1990s, beginning as an ideological reaction against the utopian ideals of Modernism. While the latter was concerned with purity of design, less-is-more and proscriptive ideas about taste and order, Post-Modernism was about ornamentation, contradiction and experimentation, acknowledging older architectural traditions and communicating through metaphor and symbolism.

C20 Society organised a Post-Modernism Conference in 2016 to raise the profile of the much-maligned style, and to highlight the threat faced by some of key examples. This was followed by a thematic listing review, conducted by Historic England, which resulted in twenty-four outstanding Post-Modern buildings being listed between 2016 and 2018. These included the Cosmic House, Kensington, by Charles Jencks and Sir Terry Farrell (Grade I), No 1 Poultry, City of London, by Stirling and Wilford (1994-98), and the Isle of Dogs Pumping Station, Tower Hamlets, by John Outram (1986-1988).

Sphinx Hill was described by Historic England in their listing report as ‘a tour-de-force of domestic Post-Modernism’, and is one of only two private houses designed by John Outram Associates. Of the practices seven surviving works, five are now listed on the national register – see full list below

Image credit: Phil Sayer / C20 Society

John Outram

John Outram (1934- ) was born in Taiping, Malaysia. Studying architecture at Regent’s Street Polytechnic and the Architectural Association in 1955-1960, his education was rooted in modernist thinking. However, subsequently working for the London County Council and then in private practice for Fitzroy Robinson and Louis de Soissons, he gradually became disillusioned and began to study traditional buildings, classicism and ancient mythology, assembling a collection of antiquarian books and travelling to the Mediterranean.

He founded John Outram Associates (JOA) in 1973, soon securing a reputation for innovative, creative and monumental buildings. Their brilliant colours and exuberant gestures often led to him being characterised as a Post-Modernist, but this belies their deeper background in architectural history, metaphysics and mythology. Outram had a keen interest in Egyptian-inspired motifs and made great use of them in his architecture. Outram has said that his practice was the only one that believed ‘tradition and modernity can be joined to make a singular novelty’.

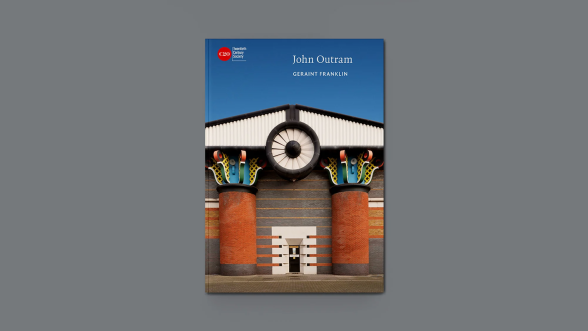

In 2021, the first major study on John Outram’s work was published by Liverpool University Press, as part of C20 Society and Historic England’s Twentieth Century Architects series. Written by architectural historian Geraint Franklin, it draws on interviews and archival research, and is richly illustrated with previously unpublished images from the practice archive, shedding new light on this important architect.

Image credit: Phil Sayer / C20 Society

John Outram’s statement on the listing designation:

“The agent of delay was my 90th birthday on Midsummer’s Day. So, another nice birthday present-like my first listing – that of the I.0.D. Pumping station on Midsummer 2017. Now only one of mine that is unaltered and undemolished remains:-The Craft Workshops at Welbeck Abbey. I don’t think I will be “that Architect who was still alive when All of his buildings were ‘Listed’. Sphinx was JOA’s second, of only two domestic projects. The first was the Grade One listed ‘New House’ at Wadhurst Park.

Sphinx, like the Welbeck Craft Workshops, was small. So it was difficult to build. Modern construction works best on larger jobs. Being small I could finish it neither with precast concrete – my ‘Blitzcretes’ and ‘Doodlecretes’ for their cost is offset by mass- produced repetition, nor brick. Bricks are too big for little houses – which is why suburbia looks so ugly. So I used render. Sphinx was a first for me. I found a firm at the annual Building Exhibition- still held in Olympia -that imported modern, “breathing stucco” from Germany. They made some plywood panels of my azure, ochre, carbon, eau-de-nil, rose and oxblood and and we held them up down by the River Isis (as the Thames is known near Oxford). They were properly admired. The cheers also came from our Oxfordshire Planning Officer. For he explained that riverside houses were an “aesthetic forestage’.” stretching up from London itself for which histrionic display was welcome! I thought of Sir Thomas More, rowing up in a barge gifted by the King, in all its finery. It was a great idea, descending from the days when streets in London were numbered upwards from the River.

Sphinx Hill would have been a ‘Number One’. Talk about ‘falling on one’s feet.’ I had suggested. after my experiences of the curiosities of British Public Taste, that Henrietta and Christoper buy a really ugly building and get a film crew to demolish it for a James Bond film. They did not have far to look. Little that is beautiful was built since WWII. But sadly the second half of my prescription failed. I learned that “demolition is fun” on my (also now demolished), Kensal Road (Workshops and Warehouses), project.

The boys smashed everything in the most unprofessional way. The men were covered in sweat and blood. Wood and rubber tyres were set alight. The Thames clay bounced as the wrecking ball fell uselessly on a pyre of rubble . The columns of smoke rose like the reltreat of Rommel from EL Alamein. An unrepeatable scene from a non-pc past! I had to phone the District Surveyor.

The ‘parti’ of Sphinx is ‘modern’ too. Its “saloon” is on the top floor and stretches right -through the house, from front to back. One rises, by a dog-leg stair from the Hall, directly into it. Up there, with truncated columns as ‘torcheres’ , one is sailing with a view over the ‘bow’ and the ‘stern’ in a mythical ‘barque of the sun’. I had wanted to script the large vaulted ceiling. But the only Clients who let me do that were in Rice University. Houston, Texas. Both in England, and on the Continent, I never found a Client who understood the 15C Leon Battista Alberti’s proposal that what a building ‘says’ is more useful than what a building ‘is’. The ‘old world’ is still too afraid of its ‘Past’ to say anything at all.

But the late Henrietta McCall wanted her house to speak to her of her love of Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. She cast barley and beer to the four quarters at its ‘topping out’. I did my best, with my ‘elastic aesthetic’ to please her. She swam every morning in water as black as outer space under a shiny vault of darkest blue for an audience of gilded green Egyptian columns. Her richly-furnished mind talked to her house. Her colleagues from the British Museum complimented her by saying her house, with her sphinxes on ‘cataracts’ running down to the River, had done more to “bring Ancient Egypt to contemporary consciousness (a.k.a. ‘life’),than many a Museum Exhibit. Our problem, today, is how to use this as a lesson in how to bring our exhausted old country ‘to life’.”

In 2021, the first major study on John Outram’s work was published by Liverpool University Press, as part of C20 Society and Historic England’s Twentieth Century Architects series. Written by architectural historian Geraint Franklin, it draws on interviews and archival research, and is richly illustrated with previously unpublished images from the practice archive, shedding new light on this important architect.

Click here to order your copy from the C20 Shop.

Image credit: John East

Listed

Lost

Unlisted

Become a C20 member today and help save our modern design heritage.